The texture of Henry James‘ prose style is one of the most easily recognized in modern literature, but very much an acquired taste. I remember the shock of my first exposure to it, years ago as a college freshman. I found it so opaque, so self-contemplative and so subtle that it was almost maddening: Nothing ever happened! But I plowed on ahead, through The Ambassadors and Wings of the Dove and The Golden Bowl, and finally, some years later, reading Portrait of a Lady, I think I finally grew into James.

He is a novelist of passions buried by manners, of fearful characters who use the rituals of proper society as a substitute for self-confidence, of people who find themselves in positions where they cannot say what they mean and, as a result, go mad or grow ill. Occasionally, a character of high spirits and unrehearsed goodwill flutters through a James novel, but she (for it is almost always a she) is usually doomed. The people who live forever in James hardly ever seem to live at all.

So that is why nothing ever seems to “happen.” Motives are hidden, not revealed. Characters are afraid of themselves and of others. They live within social walls that prohibit uninhibited expression. They communicate by infinitely subtle and textured speech, in which meanings are implied more often than stated. What is really happening in a James novel moves from the page to the reader almost by osmosis; at the end of a chapter we have absorbed the meaning without James ever having had to be so vulgar as to state it.

James Ivory’s new film “The Europeans” is based on one of James’ earlier and less complex novels, but the James style is still too much for it, perhaps because Ivory and his collaborators are so determined to make a film reproducing the real atmosphere of the Master.

The elegantly composed visuals, the stately progression of the scenes, the deliberate understatement of the dialogue, are all as “faithful” to James as a film can be. But that’s exactly the film’s problem: Ivory hasn’t found a way to make his own film, and has ended up with a classroom version of James, a film with no juice or life of its own.

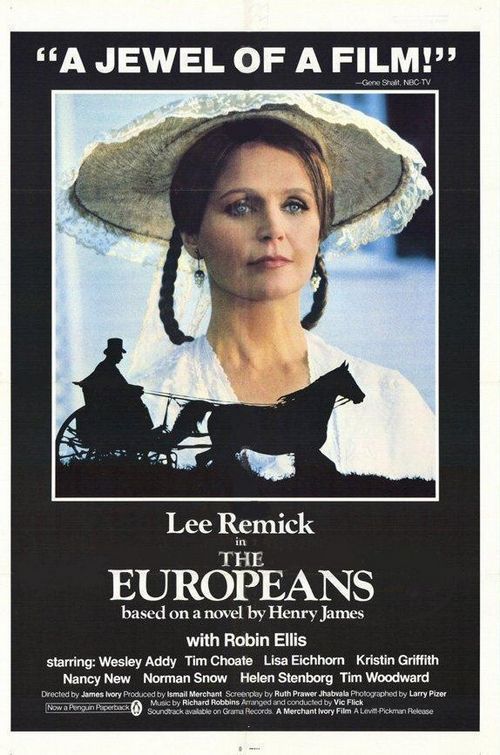

The story involves a classic James situation in which rather innocent Americans are exposed to the wiles of more worldly Europeans. The action is all within a staid New England backwater where the Wentworth family apparently spends most of its time going to church, going for walks, sitting around and clearing its throat. Into this society come two cousins from Europe: the charming Felix (Tim Woodward) and his sister, the intriguing Baroness Munster (Lee Remick). They are cultured, sophisticated, witty and broke, and, not to make too fine a point, they both need to get married.

The Wentworths put their cousins in the nearby guesthouse, and then the intrigues begin. There are only a few basic possibilities, and they are all explored. Felix undertakes to woo his cousin Gertrude (Lisa Eichhorn) away from the perspiring local minister. The baroness goes after the wealthy local landowner while also flirting with a young Wentworth heir. One of the would-be courtships succeeds, and the others fail.

Ivory follows the courtships against a backdrop of the local social life, which is extremely leisurely (nobody in this movie ever seems to work). There are church services, walks in the rain, flirtations at a dance, visits to each other’s houses, and a great deal of desultory conversation over breakfast. Everything is photographed by Larry Pizer in beautiful compositions of white frame houses, grassy meadows and autumn leaves. The movie is elegant. But nothing happens!

Or, more fairly, things happen at such a deliberate pace, and the working out of the plot is so inexorably predictable, that we don’t find ourselves growing involved. This is a film of perfect surfaces, but it doesn’t develop characters we really care about. That’s where it parts company with Henry James. The surfaces of his prose, so elaborate, so meticulous, so stubborn sometimes in circling the real content of his scenes, eventually suggests the pools of emotion beneath. But Ivory’s “The Europeans” is finally just all surface: illustrations for the novel.