“The Eighth Day” teaches a lesson that everybody piously agrees with and nobody practices: We must embrace simplicity and freedom, give ourselves room to breathe, and shake off the shackles of the lock step world. In the movie, evil is represented by a faceless giant corporation, photographed in cold shades of gray and blue. Goodness is embodied in a character who has Down syndrome, and approaches life directly, with great delight. During the course of the story he will teach the lesson of freedom to Harry, a harassed executive.

There is nothing to quarrel with here, but we must be careful before we sign up for freedom. I applaud it, but in a movie review that has a deadline and a recommended length. If I miss too many deadlines while embracing joy and freedom, I will find myself without a job. You, dear reader, can read my review and likewise subscribe to freedom. But if you are like me, reading the paper is a blessed oasis of private time in the morning before you must race out of the house and rejoin the rat race.

I’ve seen a lot of movies where simple characters teach complex ones how to relax and enjoy life. “Rain Man” is an obvious example. Offhand, I can’t recall a movie where a character starts out unfettered and free, and the movie teaches him that he needs to punch a time clock. I guess nobody would buy a ticket to that movie.

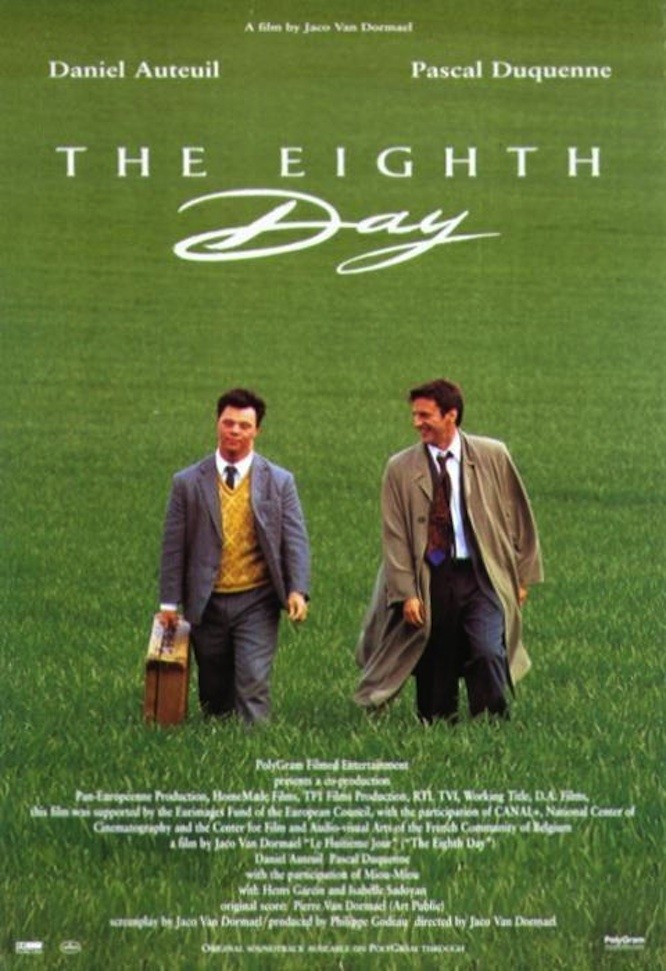

The hero of “The Eighth Day” is Georges, played by Pascal Duquenne, a professional actor in Belgium who has Down syndrome. Since the death of his mother, he has lived in an institution that looks like a pleasant place. He has a sweetheart there, and some friends, and in his dreams he’s comforted by his mother. One day a lot of the patients prepare for visits. Georges has no one to visit, but he packs his bag and sets off across the fields, his destination uncertain.

The movie’s other central character is Harry (Daniel Auteuil), whose corporate job is to teach his company’s faceless minions how to fake a smile. He is consumed by unreleased anger. His wife (Miou-Miou) has left him, he is under orders not to approach her home, and although his daughters are allowed to visit him, he forgets they’re coming. They wait at the train station and then take the next train home, furious.

Harry’s life is not worth living. In a touching scene, he addresses a chair as if his wife were sitting in it. He drives out recklessly into the rain, inviting suicide, and kills a big dog that has accompanied Georges. He is at a loss what to do. The police are no help. Eventually he finds himself saddled with Georges, and after they bury the dog they find themselves sharing life together for a few days. Harry wants nothing more than to get rid of Georges. In real life, of course, that would only take a phone call, but this is a movie.

Georges lives in a world where fantasy and reality pass back and forth through the membrane of his perceptions. He takes things literally. He believes that after you cut the grass, you should comfort it. He is visited by a singing Mexican cowboy from a Technicolor musical. When he hears the word “Mongoloid,” he imagines a world of Mongols with Chinese hats and pig-tails. He responds directly and without affectation to whatever happens. He embraces life. He goes with the flow. Whatever.

You now have everything you need to imagine the movie. It is about Harry’s gradual alienation from his corporate prison, and about the lessons Georges can teach him. About how the two men become friends. There is even a scene late in the film where Georges is reunited with some of his former fellow patients, and they commandeer a bus and drive it wildly through the streets; such an adventure is more or less obligatory for a story such as this.

Watching “The Eighth Day,” I felt contradictory impulses. On the one hand, I was acutely aware of how conventional the story was. On the other, I was enchanted by the friendship between Harry and Georges. Auteuil is a fine actor, and so is Duquenne, who belongs to a Brussels experimental theatrical troupe and approaches every scene with a combination of complete commitment and utter abandon. These two men shared the best acting prize at the 1996 Cannes Film Festival, and indeed it would be impossible to honor one without the other.

What I also liked was the visual freedom that the director, Jaco Van Dormael, brings to the screen. We see the most unexpected sights here: busy little ladybugs, and an ant being trapped inside a vacuum cleaner, and Georges walking on water, and scenes of flying and drifting, clouds and fantasies, dreams and rest. The single most enchanting moment in the film is an overhead shot, looking straight down on the two men after one has said “in a minute,” and then for exactly 60 seconds they pause, and wait, and experience a minute, so that we can, too.

“The Eighth Day” could have been a better film. Its message is too easy. It could have dealt more deeply with these characters. One can choose to reject its easy sentimentality. I eventually chose not to. I opened myself to it. Went with the flow. Whatever.