If you’ve ever enjoyed a donut that came from a pink box, you have Cambodian refugee Ted Ngoy to thank. The same goes for if you’ve been to California and tasted a donut from one of the many shops owned by many other Cambodian refugees like Ngoy, who have proven over time to be a top competitor with the likes of Dunkin’ Donuts and Starbucks.

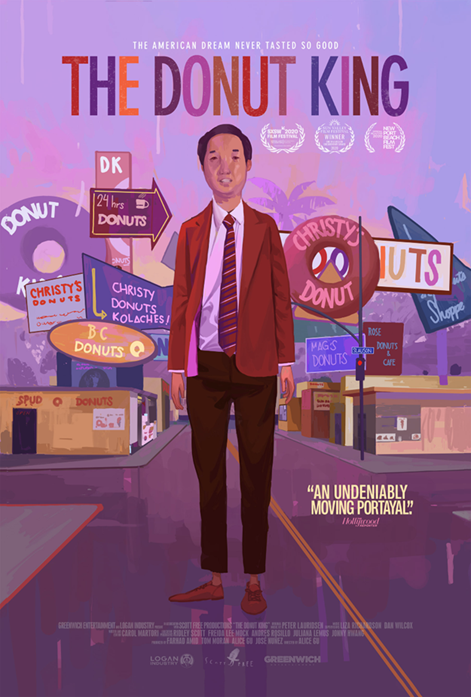

The incredible story of Ngoy—with its hard-won ascendance and tragic collapse—is captured in “The Donut King,” a heartwarming albeit scattered documentary from director Alice Gu. With its balance of poppy visuals and detailed history about both war-torn Cambodia and the business of donuts, the documentary lovingly profiles Ngoy’s life and countless other donut shop entrepreneurs like him.

By the mid-1970s, Ngoy had arrived in California with his family, having escaped the violence in a war-torn Cambodia. By chance, he learned of the irresistible smell and taste of a fresh donut, but through his incredibly hard work, he was soon able to learn the business and open up his own shop, one that appealed to a growing market. Within years, he had multiple shops and achieved financial success while constantly working alongside his family, who shared his sense of sacrifice. Ngoy had some brilliant ideas that changed the donut industry (like using pink boxes instead of white ones, originally to save money), and within a few years, he became a millionaire. The documentary takes a nuanced approach to the oft-touted American Dream, showing the extreme dedication and hard work required to even proliferate such a rosy-eyed view of success.

Ngoy might be referred to here as The Donut King, but his legacy concerns more than his own success. As Gu’s film lovingly illustrates, it’s about the other refugee families and generations that he supported and who then followed his regimen and earned their own small fortunes. (By the 1990s, 80% of the donut shops in California were owned by Cambodian families.) It’s particularly fitting that the documentary doesn’t begin with Ngoy but with a 29-year-old woman named Mayly Tao, who comes from a new generation of donut shop innovators. She speaks of the reality of being a child of an immigrant family who runs a small business (“You can definitely identify with spending a lot of time in the shop”) and follows the same hard schedule—getting up before dawn, leaving her home to make donuts. In this case, it’s at the social media-savvy DK Donuts & Bakery, which her mother founded in the early ’80s, and which she now owns.

In telling this story, Gu is excessively preoccupied with holding your attention, using up all of her tricks to the point of losing some freshness. It’s bright and soundtracked with more donut-inspired hip-hop tracks than you can imagine, and doesn’t hesitate to repeat them. It also repeats some visuals—particularly of donuts falling in slow motion—in a way that shows the documentary is a little thwarted in how to make this vibrant world visually engaging for its whole run-time. The saga that Gu unravels is always interesting, but it’s the storytelling that can be a little disorienting as it jumps back and forth between past and present or is in danger of abbreviating passages. The “fall” in Ngoy’s story, in particular, leaves you wishing that Gu went into more detail about how Ngoy was essentially dethroned by his own actions. It’s a genuinely shocking and tragic part of the story, and the documentary feels like it has too many other things on its mind to engage it properly.

But what’s impressive about the documentary, in particular, is how it captures a wide range of personal histories, placing viewers in the various emotional journeys of different Cambodian refugees who call Ngoy “Uncle Ted.” Ngoy’s family was relatively lucky in getting out of Cambodia and finding a life in America, but others speak of their horrific experience in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge in the mid-1970s, in which donuts seem like they exist on another planet. The film humanizes so many donut shops and the people behind their counters while getting a larger message out without having to make its modern relevancy obvious—here are some incredibly strong Americans who were welcomed by a country that, at the time, believed in outsiders instead of looking at them as some threat. They have all worked incredibly hard, and the film is incredibly proud of them and what they represent. Such support is infectious.

Now playing in select theaters and virtual cinemas.