“The Crime of Father Amaro” arrives surrounded by controversy. One of the most successful Mexican films in history, it has been denounced by William Donohue of the Catholic League for its “vicious” portrait of priests; on the other hand, Father Rafael Gonzalez, speaking for the Council of Mexican Bishops, calls it an “honest movie” and describes it as “a wake-up call for the church to review its procedure for selecting and training priests and being closer to the people.” Both sides treat the film as a statement about the church, when in fact it’s more of a melodrama, a film that doesn’t say priests are bad but observes that priests are human and some humans are bad. What may really offend its critics is that young Father Amaro’s crime is not having sex with a local girl and helping her find an abortion. His crime is that he covers up this episode and denies his responsibility because of his professional ambitions within the church. Young Father Amaro thinks he has a rosy future ahead of him.

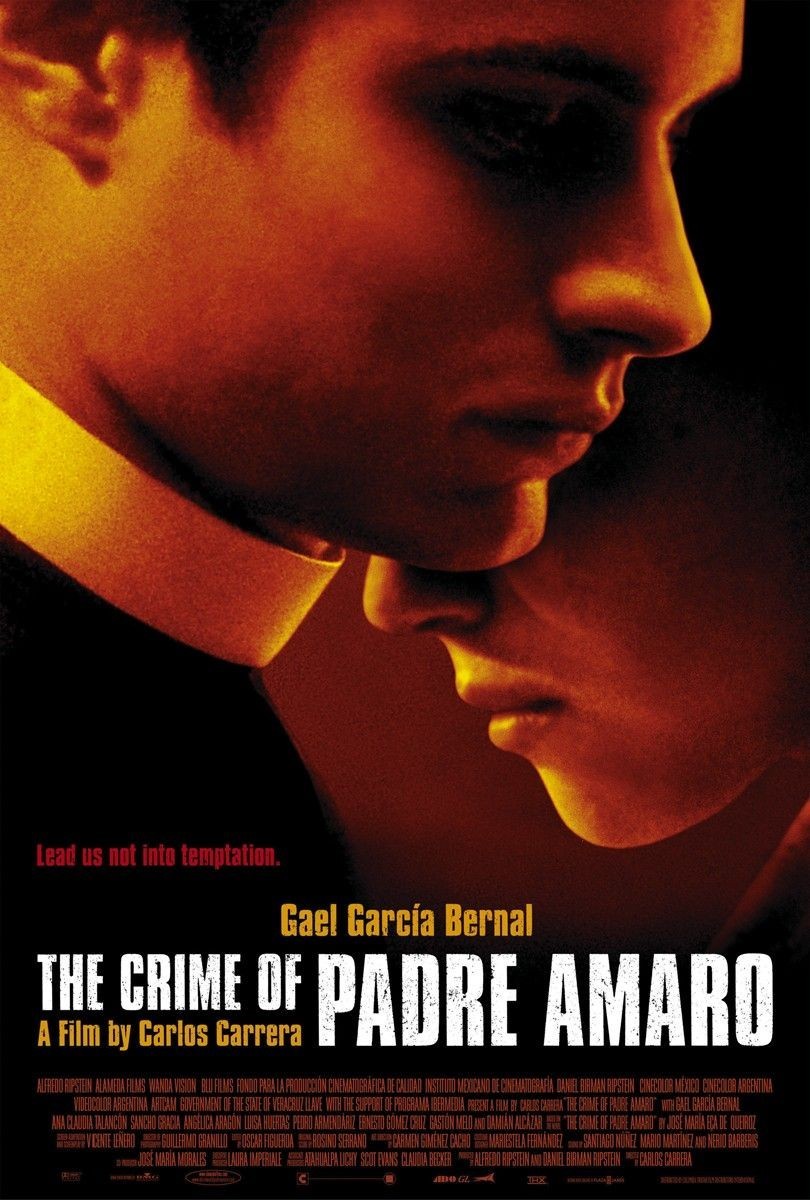

The movie is based on an 1875 Portuguese novel by Eca de Queiroz, transplanted to modern Mexico. It gives us Padre Amaro (Gael Garcia Bernal) as a rising star in the church, a protege of the bishop (Ernesto Gomez Cruz), who ships him to the provincial capital of Los Reyes to season a little under an old clerical hand, Padre Benito (Sancho Gracia). Benito has been having a long-running affair with the restaurant owner Sanjuanera (Angelica Aragon), whose attractive daughter, Amelia (Ana Claudia Talancon), may possibly be theirs. There is the implication that the bishop knows about Benito’s sex life but doesn’t much care and sends Amaro to Los Reyes for exposure to the church’s realpolitik; that the bishop knows Benito’s ambitious program of hospital construction is financed through money he launders for local drug lords. It is likely the bishop approves more of priests like Benito, who raise money and get results, than of another local priest, Padre Natalio (Damian Alcazar), who supports the guerrillas waging war against the drug lords.

Once established in the local basilica, Amaro cannot help but notice the fragrant Amelia. And she develops an instant infatuation with the handsome young priest, whose unavailability makes him irresistible. Amelia has been dating a local newspaperman named Ruben (Andreas Montiel) but drops him the moment Amaro expresses veiled interest. Soon Amaro and Amelia are violating the church’s laws of priestly celibacy, and eventually she is pregnant, and this fate leads them to an illegal abortion clinic on a back road in the jungle.

The film has been attacked for the sacrilege of showing a priest paying for an abortion, but since he related to Amelia as a man, not a priest, there is a certain consistency in his behavior. It is also consistent that he would attempt to hide his crime, because, like Benito, he finds it easy to make himself a personal exception to general rules. There is still a little seminary idealism in Amaro, enough to be shocked that Benito is taking drug money to build the hospital, but part of Amaro is already warmning to Benito’s logic: “We are taking bad money and making it good.” This theology is not unique to that time or place, or even to that church; we are reminded of the CIA using drug money to finance its friends.

The film is directed in a straightforward way by Carlos Carrera, who makes it direct and heartfelt, like a soap opera. The presence of Bernal in the cast is a reminder of his work as one of the two young men in “Y Tu Mama Tambien” (2001), a film where the ethical issues were more complex and deeply buried. There are no complexities here, unless they involve Amaro’s gradual corruption in the real world of church politics and money.

Is the film harmful to the church? I tend to agree with Gonzalez, who finds that fresh air is a help, not a harm. Donohue and his league predictably denounce every movie that is unfavorable to the church, undeterred by the fact that their opposition helps publicize the films and sell tickets (no movie has even been harmed by being called “controversial”).

Predictably, the film’s critics are most upset by Amaro’s sexual behavior, when in fact the film’s real questions run deeper, and are political: Has the church sometimes kept company with unsavory sources of financing? Is the policy of celibacy more observed in the breach than in the observance? Are laws against abortion made by men in the daylight and violated by them in the darkness? Is the church more comfortable allied with an amoral establishment than with a moral opposition? These questions are lost in the excitement about sex, which is often the way it works: Carnal guilt clouds our minds, distracting us from more important issues.