“The Conquest,” a feature about recent French politics, makes me yearn for a similar American treatment of our own scene. Scored with Felliniesque circus music, it depicts such figures as French presidents Nicolas Sarkozy and Jacques Chirac and their wives on a merry-go-round of vanity, vulgarity and viciousness. I’m not an expert on French politics, but I gather the director and co-writer Xavier Durringer has worked by simply cranking up the energy under what everybody knows really happened. The result at times approaches screwball comedy.

But no, this isn’t deliberate comedy. It’s essentially realistic. It’s simply that the real lives of these figures are funny. Most of the major players here are in the same political party, we hardly hear about their opponents, the focus is on infighting within the government, and they warmly hate one another. As I follow our own GOP caucuses in Iowa, I’d love to see this approach adapted to Newt Gingrich’s real feelings about Mitt Romney, and listen in on his language.

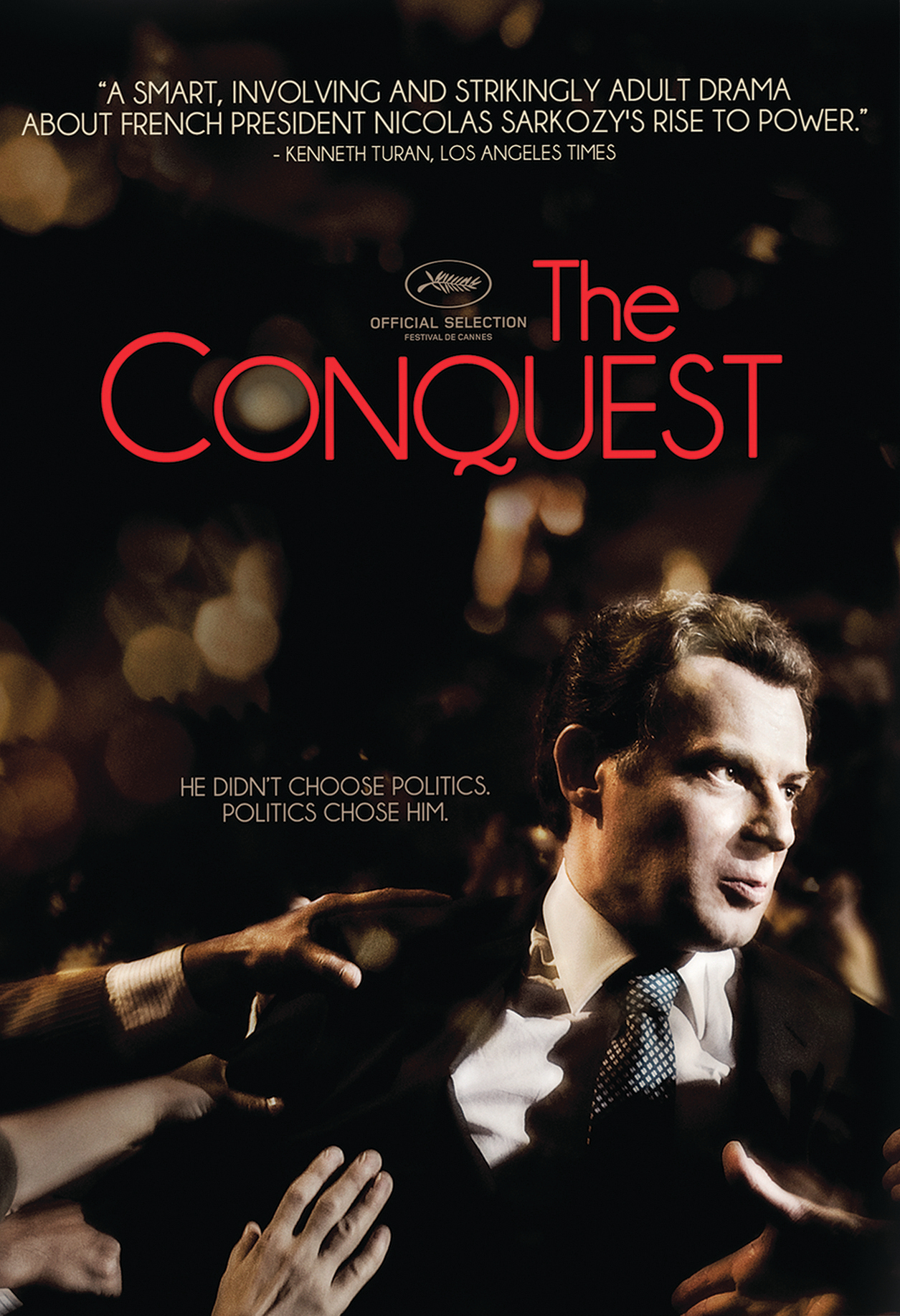

The film opens with a problem that would become chronic with Nicolas Sarkozy (Denis Podalydes), who was then a minister angling for higher cabinet posts in the government of Jacques Chirac (Bernard Le Coq). It is an election day, and his wife, Cecilia Sarkozy (Florence Pernel), is nowhere to be found. Sarkozy refuses to be seen voting without his wife at his side, and Cecilia is so mad at him, she refuses to appear.

French political spouses obviously lack the rigorous training on the campaign trail that American partners receive. In our country, a spouse is in it for the long haul and must be prepared to spend 18 months in an endless series of campaign appearances, smiling and waving, loyal and staunch, every word and gesture under close guard. French campaigns are most shorter and more brutal.

In “The Conquest,” Cecilia (Sarkozy’s second wife) occupies an intriguing dual role: (1) She is Sarkozy’s most influential and trusted adviser, (2) She hates politics and considers a political campaign to be a sadistic form of reality television. It is also apparently the case that the Sarkozy marriage is being held together with duct tape and bailing wire. At times the two can barely stand to be in the same room together, and yet fate has yoked them to a common goal. They want power, and they want to win.

Sarkozy emerges here as a fascinating figure. Small and hyperactive, a campaigning welterweight, he is nakedly ambitious, but so are they all. After a seemingly cordial meeting with Sarkozy, Chirac tells an adviser: “The little bastard wants my job.” To become president, Sarkozy envisions a series of more and more important cabinet posts, and to keep him in check, Chirac envisions a series of less and less important posts. Since it is clear to everyone that this is the game, it contributes admirably to the amusement level of the French body politic.

To be a candidate for office is a condition few of us would wish upon ourselves. Even having pleasure at mealtime, a sacred occasion in France, is diminished. Some of the film’s more absorbing scenes involve the major players, sometimes together, often just as twosomes, dining elegantly in ornate rooms of state while smiling pleasantly and cordially insulting each other.

I don’t believe it’s necessary for a non-French viewer to know a lot about French politics to enjoy this film. What you need is an appreciation of human nature. The actors, especially Denis Podalydes and Florence Pernel as the Sarkozys, provide in their performances all the personal background you would require. We know the film is about politics, we can see how the characters feel about each other, we can apply their behavior to the politicians we know. It’s a macabre but not boring process.