I had no idea what happened after Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans and the Gulf Coast. No idea. I read the papers and watched the news on TV and I had no idea. I learned the things they like to report: how hard the wind blew, how many inches of rain fell, what the early death toll was, how victims were living on a bridge, how people came to be sheltered and/or imprisoned in the Superdome. But then another big story came along, and the news moved on, and I didn’t think about Katrina so much.

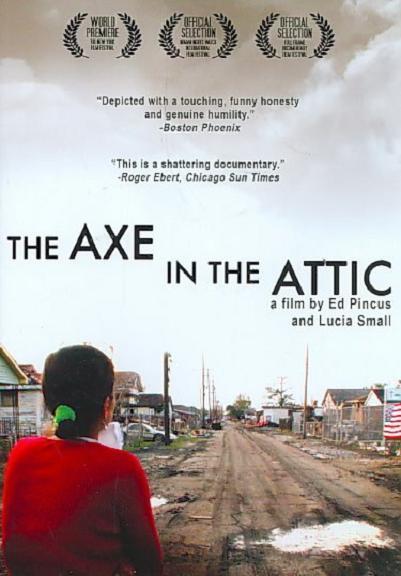

Ed Pincus and Lucia Small saw the pictures on television and decided to do something. They took an HD camera and set off on a 60-day road trip from their home state of Vermont to Louisiana. Along the way, they interviewed refugees who had settled for the time being in Philadelphia, Cincinnati, smaller cities and government-funded trailer parks. “The Axe in the Attic” is their story of that journey.

When they arrived in the disaster zone, the sights were overwhelming. Square miles, whole counties, were destroyed. Families were uprooted. A way of life was torn apart. And the people they met were outraged by the pathetic inadequacy of the response by the federal government. FEMA, the optimistically named Federal Emergency Management Agency, was a target of scorn.

Not only did FEMA set up a bewildering barricade of red tape, in many cases it treated the hurricane victims as if they were homeless by choice. The National Guard was no better; on the bridge, troops leveled weapons at the refugees. The reason was not hard to understand: Many of the refugees were black. It was as if the government was trying to drive them out of the city by bulldozing rebuilding efforts and blocking relief agencies from delivering food and water, which would “only encourage people to stay.”

Not only blacks are angry. The film also listens to white victims, who are angry on their own behalf, and in many cases on behalf of blacks they have seen targeted for abuse rather than aid. They didn’t know, but I have since learned from another documentary, “I.O.U.S.A.,” that federal accountants uncovered massive theft and fraud of FEMA funds, which paid for cars, vacations, champagne, lap dances and porno films.

The hurricane didn’t merely destroy by wind and floods. The storm waters were contaminated by chemicals, and even weeks later returning citizens had to wear face masks. Any clothes that got wet had to be destroyed; they burned the skin.

One opinion about the victims was that instead of expecting government aid, they should have gotten jobs. This at a time when tens of thousands of jobs had disappeared. The film talks with one man who had to walk 2½ hours each way to a low-paying factory job because he couldn’t afford a bus pass. He asks Lucia Small for money to buy a pass. She is conflicted: “Documentary ethics say we shouldn’t pay people.” I say to hell with documentary ethics, buy the man a pass.

Her moral argument is part of an element of the film I could have done without: Small and Pincus, partners in filmmaking but not in life, devote too much time to themselves. Their arguments quickly lose our interest. The film should have allowed the victims to speak for themselves instead of going off topic to become the story of its own making.

All the same, this is a shattering documentary. The witnesses in it mourn the loss of their homes and possessions, but also their loss of a city. “In New Orleans, nobody ever locked a door,” one woman says. She saw her friends every day. She is now living in Florida: “I don’t know anyone. Saturday at the mall is their family day.”

The title? After an earlier hurricane, many residents learned to keep an ax in the attic, in case the waters rose so high they had to hack holes in their roofs. “That’s why you saw so many people on roofs.” Another says, “They say we got a warning. They got a warning six years ago, to strengthen the levees.” Strange that a levee separating white and black neighborhoods gave way only on the black side.

Note: Co-director Lucia Small will conduct Q&A sessions after all screenings Friday and Saturday at Facets. She also will participate in a panel discussion with policy experts at noon Saturday.