The rewards of selling drugs are so small compared with the risks you run and the price you pay. That is the remorseless lesson of “Sweet Nothing,” which tells the story of a Wall Street worker who wants a little more money for his family, and ends up broke, addicted, sought by the police, and without his family.

One of the key images in the early part of the movie shows him smoking crack for the first time and saying, “So that’s what I was missing.” One of the key images from the closing scenes shows him huddled against a wall, sucking on a piece of candy, waiting for drugs while watching the clock advance one excruciating second at a time. Here is a man who had no idea at all how much he could be missing.

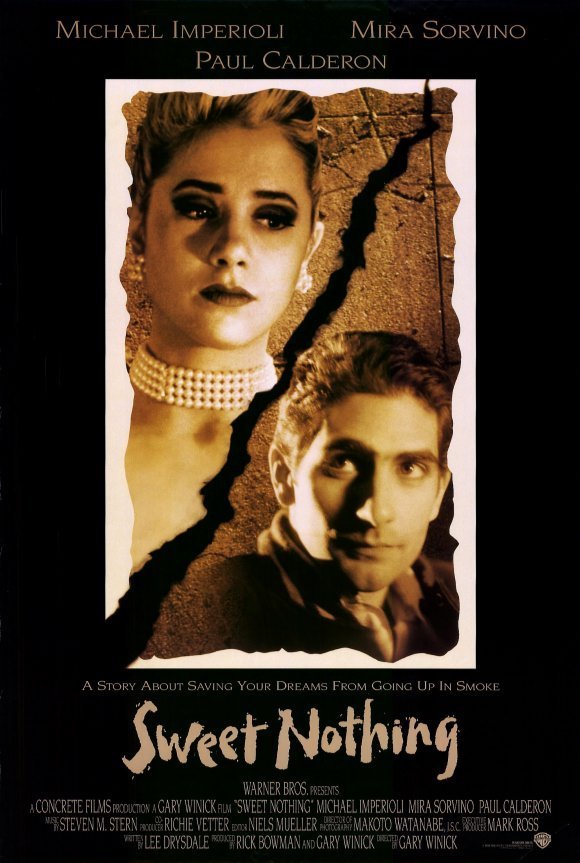

The film is about Angel (Michael Imperioli), who in the opening scenes celebrates the birth of his second child. He visits his wife Monika (Mira Sorvino) in the hospital, and then goes out to celebrate. His friend Raymond (Paul Calderon) offers him a hit from a cocaine pipe, and he likes it. “Give me another,” he says, perhaps unaware of George Carlin’s famous line, “What does cocaine make you feel like? It makes you feel like having some more cocaine.” Raymond tells him the truth: “People sell their front doors for this stuff.” Angel doesn’t care, because already he is ready to sell his own front door. Before long he’s doing some dealing, finding customers at work, talking about how he can clear $1,000 a week. One night he puts a pearl necklace around Monika’s neck, and she glows with delight. She allows herself to think that maybe this thing will work–that Angel can make extra money, the family can benefit, and somehow nobody will get hurt. One characteristic of all addictions is that they create a state of compulsive self-monitoring. The user is constantly asking, How do I feel? Have I had enough? Too much? Can I get more? Am I in trouble? Although using the drug or drink of choice seems to create a state of benevolence and relaxation, in fact it builds a wall that closes out other people. When a user is high he smiles at you, but it’s because of how he feels about himself, not because of how he feels about you.

“Sweet Nothing” understands this process. Gary Winick, who directed, and Lee Drysdale, who wrote the screenplay, subtly mark out the stages in the progress of Angel’s addiction. He defends himself by claiming the best motives (he is dealing drugs to help his family), although his real motive is to get high, and the family obviously suffers. They move to a shabby apartment (“just for a little while”). There is no food in the house. Monika cannot cope by herself. Eventually even the small son knows that the man on the corner is a drug dealer. One night, desperate for drugs, Angel dumps his kids at his in-laws’ house, terrifying everyone in the process.

Nor are drugs kind to Raymond, the friend. He seemed better able to handle them than Angel. Perhaps he was wise enough to balance his business against his addiction. But eventually the cops are looking for him, and someone is dead, and everything is coming to pieces. Angel’s life in the closing stages of his addiction can be symbolized by that guy on the old TV shows who tried to keep a lot of plates spinning on the tops of poles, all at once.

Michael Imperioli has been in some two dozen movies (including “Last Man Standing”), often playing a tough kid, an outsider, troubled, complex. In “Sweet Nothing” he shows a new maturity and command in his acting, maybe because he is given a key role that runs all the way through. He doesn’t fall for the actor’s temptation of making too many emotional choices; he understands that many of Angel’s problems are very simple: He wants to use more drugs than he can afford. For Mira Sorvino, this is a new kind of role, and she is very good in it, as a woman who wants to hold her marriage and family together, who is willing to give her husband the benefit of the doubt, who believes more than she should, stays longer than she should, and finally finds the strength to act for herself.

Winick uses an interesting narrative device–the story is told in a journal being kept by Angel–and the journal segments suggest Angel has arrived at some sort of end to his journey. Wisely, the movie doesn’t spell out the details. We can arrive at our own conclusions. “If I were still using,” addicts say, “I would be dead.” There is a logical paradox there, but the message is clear enough.