In every family, there’s a precocious little kid who is always lurking around amongst the adults. They’re often within earshot of things they may not understand and to which they should definitely not be privy. I was one of these kids, and in the more comprehensive glow of my adulthood, I realized I’d gained quite an education while hanging out with the adults. But as a kid, I was clueless, entangled in my own narcissistic wavelength of childhood goings-on to truly appreciate the nuggets of truth, wisdom and trouble falling all around me. Looking back, I feel a sense of bemused frustration that I didn’t catch on to things earlier.

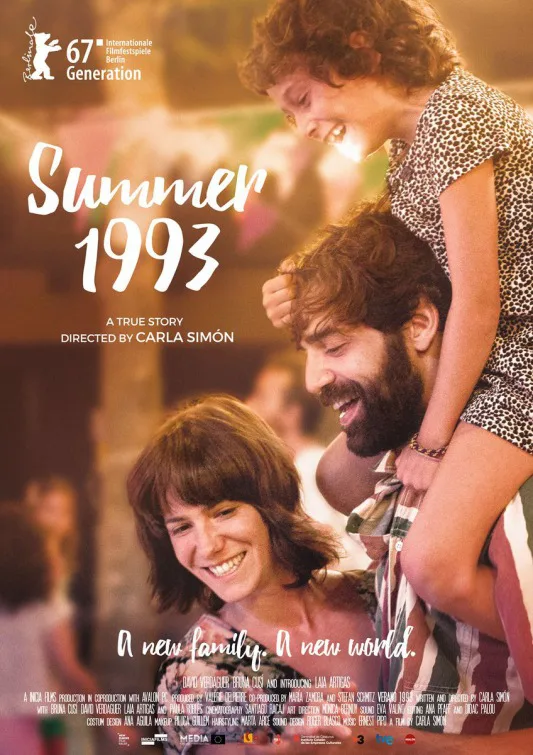

Writer/director Carla Simón’s autobiographical film “Summer 1993” understands this feeling. It’s told from the perspective of six-year-old Frida (Laia Artigas), though “perspective” may be too misleading as a description. This is not a film for children, but the camerawork and the emotional undercurrents most often evoke the physical viewpoint, level of understanding and sensory processes of a child. We as adults must deduce the film’s most crucial pieces of information as they fly over Frida’s head. Simón does a good job training our eyes and hearts to once again engage the childhood perceptions that were shutdown by our own ascent into maturity. For example, an early bathtub scene between Frida and her cousin Anna (Paula Robles) frames Frida’s uncle Esteve (David Verdaguer) as the “villain” spoiling their fun. You can practically feel the disappointment beaming off the screen.

Esteve and his wife, Marga (Bruna Cusí) are the caretakers who have moved Frida from Barcelona to a rural village that registers as a bit of culture shock for the young girl. Frida’s parents are both deceased, and their cause of death is never explicitly stated. However, the foreboding sense of shame whenever they are mentioned, and the film’s reliance on blood as a repeated visual motif, leads us to infer that Frida’s parents succumbed to AIDS-related illnesses. Simón isn’t stingy with the details; rather, she parses them out in a way that requires viewing “Summer 1993” in a different manner than most movies. Frida is in her own little world and we are primarily there with her, so it’s up to us to catch what’s on the fringes of this universe.

One of the ways “Summer 1993” crafts its overall feel is the casual manner in which events unfold. Several scenes ramble on with a lackadaisical pacing of an afternoon of youthful play. It evokes memories of one’s own past summers, when school was out and the time before the streetlights came on seemed infinite. Anna and Frida bicker and play while the adults cater to far more important matters that will invade and corrupt their bubbles of innocence later. For now, adulthood—or the kids’ imitation of it—intervenes in a much sweeter, more humorous manner in a well-crafted scene of dress-up featuring Frida as a diva caricature barking out orders and basking in her own imagined greatness.

Of course, all idylls are temporary. Simón bypasses most of the sentimentality normally associated with a film like this, opting instead for a mature exploration of grief and its aftereffects. One gets the sense that Simón is inspecting her childhood processing of loss onscreen through the filter of the reminiscing adult behind the camera. “Summer 1993” dissects Frida’s concept of what happened to her parents and why she is now her aunt’s ward so as to better understand how she developed into the adult she became.

This idea really spoke to me; at one point, I gravitated toward my memories of losing my grandmother when I was four, and how I had no understanding of what that meant nor why everyone was crying. My cousin, who was not much older than me, gave me my first lesson on what losing someone meant. That experience shook me enough to etch itself into my memory so well that I could currently reach back into myself to feel the scar it left, forcing me to reconcile the original feeling through a far more adult definition.

“Summer 1993” feels like that, most notably in late scenes where Frida suddenly becomes antagonistic toward her playmate. She abandons Anna in the woods and makes plans to run away from her aunt’s stricter household. At first, I thought Frida was being a ripe pain in the ass, but then I figured out what Simón was showing me. A bit of worry accompanies these scenes, as we are so conditioned as viewers to expect the worst in situations like this. But Simón defies our expectations yet again, acknowledging the darkness without ignoring the light. There’s an old saying about kids that goes “little pitchers have big ears.” “Summer 1993” is all about the emotions that get poured into those pitchers.