Some of my colleagues on the editorial page deplored the Thomas-Hill hearings because they presented the spectacle of two black professionals at war with one another. White professionals are at war with each other every day, and nobody thinks to write an op-ed column about them, but in the minds of these columnists any black is thought to represent all blacks, and so it creates a “bad image” when two of them disagree publicly.

This opinion is silly, to the extent that it is not tragic.

It reflects a narrow view of the diversity of black people in America – so narrow it does not perceive the real image of the Thomas-Hill event, which showed millions of TV viewers a spectrum of many different black professionals, all speaking for themselves.

Yet there is a persistent view, held by many blacks and whites, that some mystical reality known as the “street experience” is what authenticates a black in America, and that a black professional – a corporate executive, say – is somehow not quite authentically black. This view is examined in Kevin Hooks’ “Strictly Business,” a comedy that contains some challenging implications.

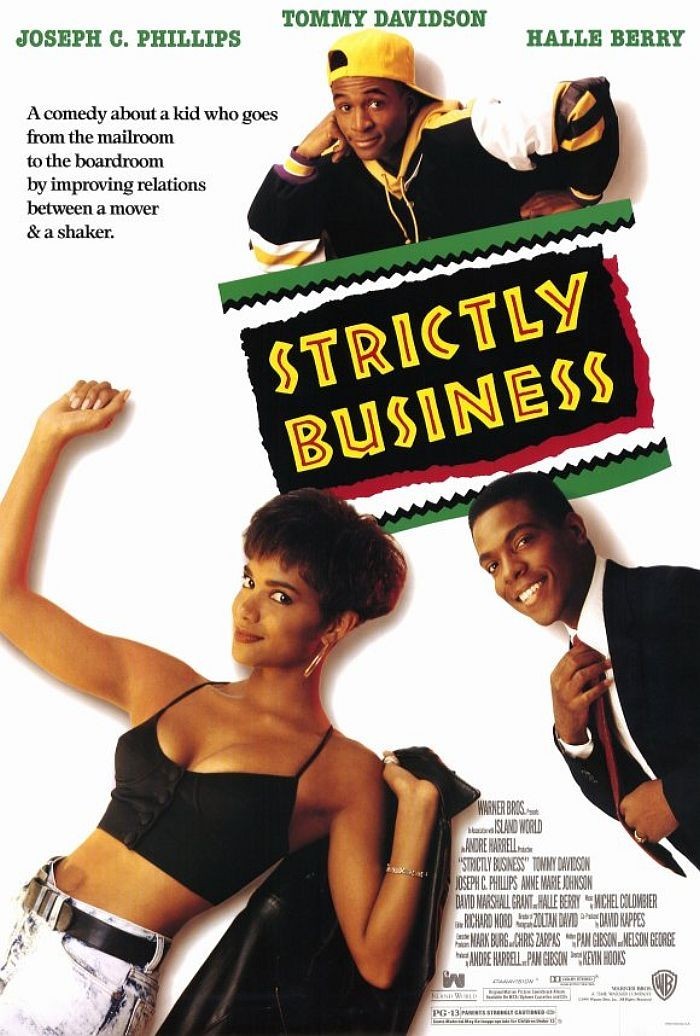

The movie stars Joseph C. Phillips (Bill Cosby’s TV son-in-law) as Waymon, a fast-rising young executive in a big Manhattan real estate firm. Tommy Davidson (from “In Living Color”) plays Bobby, a mailroom clerk who dreams of being promoted to a trainee position one day. But Waymon, who is Ivy League, and Bobby, who is from Harlem, come from different worlds. Yes, Waymon would like to help the young brother, but a word like “brother” comes uneasily to his lips. Then lightning strikes when he sees the beautiful Natalie (Halle Berry), dreams of dating her, and discovers that Bobby knows her and will arrange an introduction in return for a step up the corporate ladder. Waymon immediately agrees, setting in motion a plot that takes him on a tour of the black urban culture he has avoided up until now.

The business ethics involved here are not spotless, but that’s not the point. What we have here is a movie that begins with one premise – Waymon should learn how to act like a brother – and ends with the rather surprising premise that Bobby is going to have to get his act together if he wants to climb the corporate ladder.

Along the way, there is a comedy plot involving unscrupulous real estate investors, a skyscraper that may or may not get sold, and the beautiful Natalie. There are moments that work, and others that do not (no young man, not even Waymon, could be as uncoordinated on a dance floor as he seems to be). But beneath the plot, which is routine, are a lot of assumptions that are not.

The movie questions the notion that black “authenticity” is only to be found on the streets or in clubs, in rap music or high-fives. There is a reality here in which young Bobby can indeed get a trainee position and start climbing the corporate ladder – and Bobby likes that idea. Cleverly and subtly, the movie undercuts the negativity of dozens of black movies, which taught that the only correct stance toward the white corporate world was to reject it.

Waymon, in a lot of earlier movies, would have been portrayed as a brother in need of soul (at one point Bobby calls him “Sidney Poitier,” not intended as a compliment). “Strictly Business” plays with that notion in order to correct it. Waymon wants to be made vice president and earn a lot of money – and, in this movie, that is presented as the kind of authentic experience that also has something to be said for it.

Seen as entertainment, “Strictly Business” is passably fun, and effectively acted by Davidson, Phillips and Berry, who generate their characters with a lot of energy. Seen as a marker in the field of pop culture, “Strictly Business” may represent a turning point like the Thomas-Hill hearings. Here, as there, black professionals are no longer willing to suppress their own personal opinions in order to reflect current political orthodoxy. Ten years ago, this movie would have ended with the executive getting a big laugh by using a familiar 12-letter word. “Strictly Business” ends with the kid putting on a suit and tie.