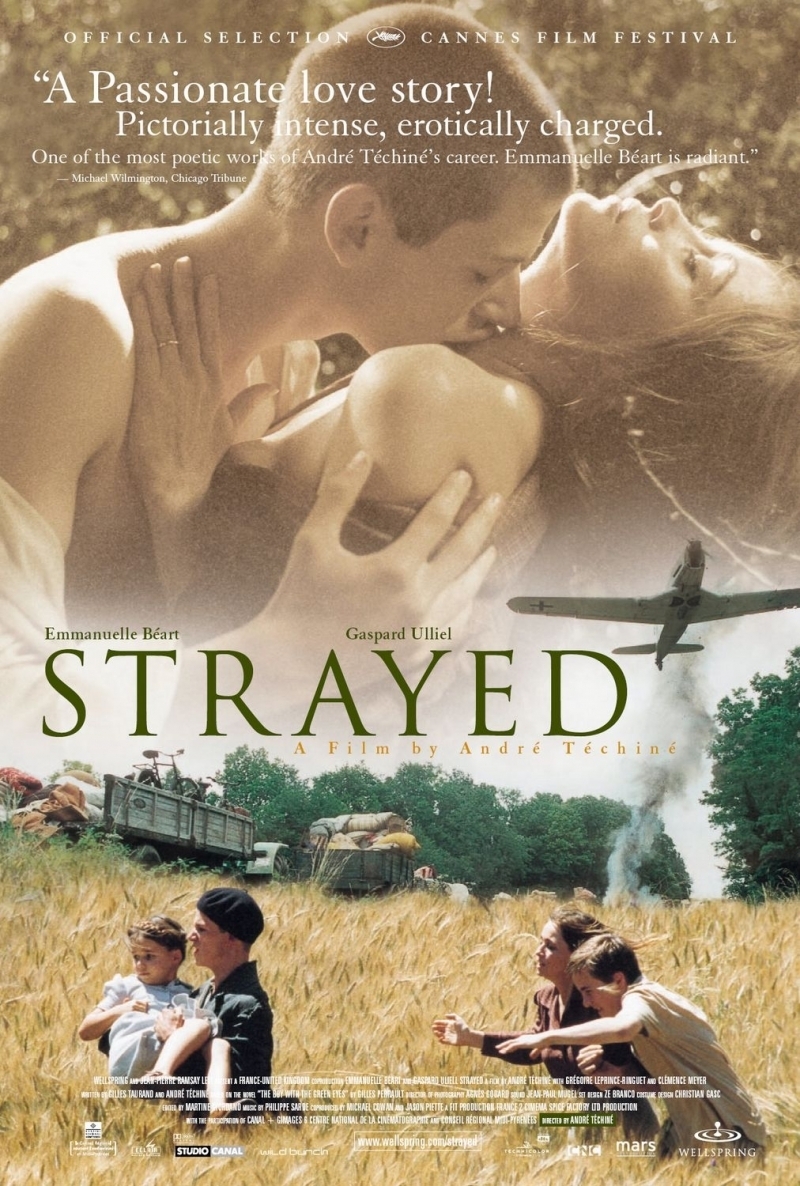

Who is this Yvan, this boy with the shaved head who has crawled out of the mud to lead them to safety? And why should she trust him? Odile (Emmanuelle Beart) is a bourgeois Parisian woman with two children and no way to protect them, and Yvan (Gaspard Ulliel) has a toughness that is reassuring and at the same time menacing. She really has no choice but to follow him into the forest, after Nazi planes have strafed and bombed the column of refugees streaming south from Paris.

It is 1940, and all of the certainties of Odile’s life have evaporated. She is a pretty widow in her late 30s, a teacher, who fled Paris and joined the flight from the Germans with her 13-year-old son Philippe and her daughter Cathy, who is 7. Her children trust her, but she doesn’t trust herself, because her experience and values are irrelevant in this sudden war. “It’s every man for himself,” someone shouts on the road, not originally but cogently, as bullets kill some and spare others.

Yvan is tough and sure of himself, and her instincts as a teacher tell her he is dangerous. The teenager Philippe is frightened but more realistic; he believes they need this strange young man. Yvan has a sweet side and seems to want to help them; there is perhaps even the suggestion that he needs this family to replace one he lost, and he needs this chance to be helpful and competent. Or perhaps the fact that Philippe secretly bribed him with his father’s watch persuaded him to stay; we never know for sure what he’s thinking.

“Strayed” begins and ends with facts of war, but it is really a film about the nature of male and female, about middle-class values and those who cannot afford them, about how helpless we can be when the net of society is broken. The French director Andre Techine, no sentimentalist, creates a separate world for his four characters, and the war goes on elsewhere.

Separated from the other refugees, they walk through a forest of such beauty that war seems impossible and sleep under the stars. The next day, they come upon a country home, comfortable, isolated and tempting. The owners have fled. Yvan believes they should break in and stay there for a while; the roads are mobbed, there is no sure safety in the south, and no one will look for them here. Odile argues that the house is private property. Her bourgeois instincts are so strong that she would sleep with her children in the woods, or try to rejoin the exodus, rather than break in. For Yvan, there is no choice: They must survive.

We realize that the war is very new to her, that she clings to the certainties of her ordered life and must learn that the rules have changed. They break in, of course. There is a wine cellar, many bedrooms, some food. Yvan hunts for game. Odile establishes a domestic routine. They could almost be on holiday, the children vibrating with the sense of adventure, Odile putting good French food on the table, and Yvan … Yvan … enjoying it, too, but on guard, and always aware of their danger. Their danger and, we sense, his own.

When you put a beautiful woman and a forceful young man in an isolated situation where they must live closely together, sexual tension coils under the surface. At first it is not obvious, because Odile’s bourgeois certainties make it impossible that she could sleep with a rough working-class stranger 20 years younger. And there are the children, although Philippe admires Yvan: Here is an older brother, or perhaps a father figure, who can protect them when his own father has failed.

There are certain mysteries, which I will not reveal, involving secrets Odile keeps from Yvan and those he keeps from her, and certain questions about how long they should stay in the house — questions that seems to depend, in Yvan’s mind, on more than the simple matter of survival. There are things Philippe observes and keeps to himself. And always there is the knowledge between Odile and Yvan that they could sleep together, that the nature of their relationship is shifting, that the war has changed the rules and that Yvan has become necessary to her family.

We sense the story will not end here, and we know this temporary family cannot live in this house forever, with time suspended. We are not sure how near a town might be, and Odile wonders why the telephone doesn’t work. Someone will find them, and what will happen then? Those questions occur to us as they occur to the characters, adding an urgency, an unreality, as the days pass comfortably. Techine, a master of buried power struggles, increases the level of uncertainty and apprehension until we know something must happen, and then something does, and the essential natures of Yvan and Odile, and their way their society formed them, becomes clear.