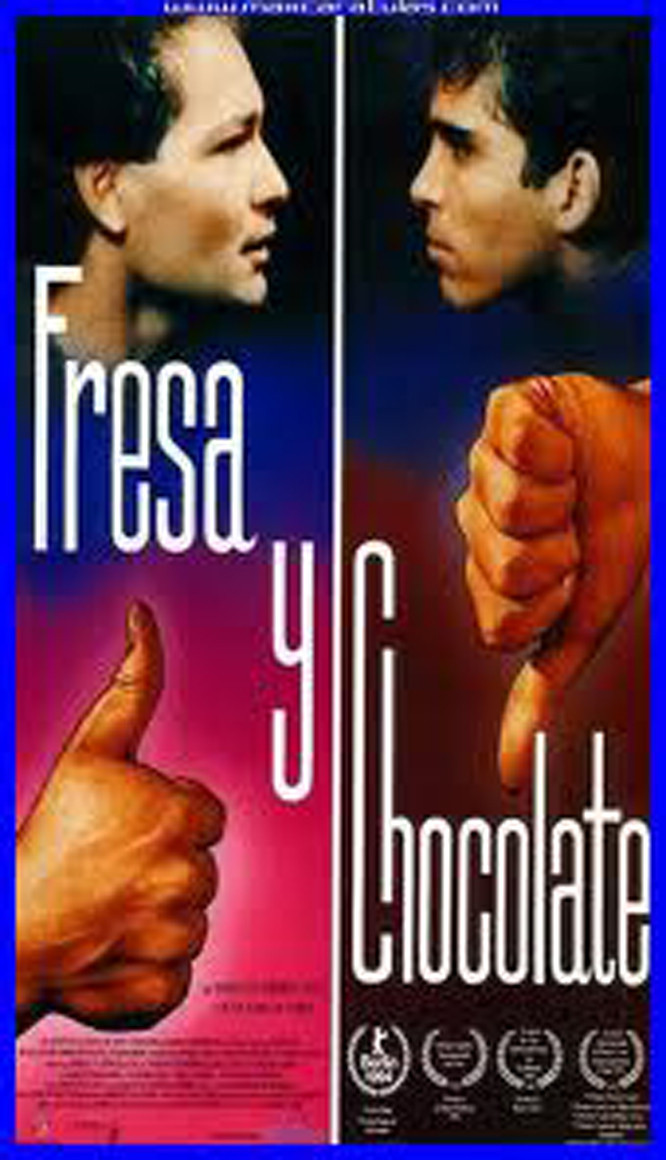

“I knew he was homosexual,” the young man explains to his friend, “because they had chocolate ice cream, and yet he ordered strawberry.” Thus does the shortage of consumer products in Castro’s Cuba reveal the inner workings of the libido.

The young man’s name is David (Vladimir Cruz), and he recently had a disenchanting experience with his fiancée. They went to a cheap hotel to make love for the first time, but she was dismayed by the shabbiness of the surroundings and could not understand how the man who loved her could bring her there. David was understanding, they left without making love – and the next time we see them, it is at her wedding to another man.

So David is on the rebound that day in the park when Diego (Jorge Perrugoria) sits at his table and starts to eat the strawberry ice cream. Diego is obviously gay: He’s swishy, wearing his sexuality as a badge of honor. And he has eyes for the handsome young David, inviting him back to his flat for coffee, and then staging a fake scenario where the coffee spills on David’s shirt. Diego insists David take it off so he can wash it, and . . .

And nothing unfolds as we expect. “Strawberry and Chocolate” is not a movie about the seduction of a body, but about the seduction of a mind. It is more interested in politics than sex – unless you count sexual politics, since to be homosexual in Cuba is to make an anti-authoritarian statement whether you intend it or not.

The movie has been directed by Tomas Gutierrez Alea, at 72 the greatest of Cuba’s filmmakers and one of its most contradictory. An early supporter of Fidel Castro and the head of the revolution’s underground film unit, he made “Stories of the Revolution” (1960) about the overthrow of the Batista regime. He founded the national film unit. Yet his own films have questioned life under Castro: The famous “Memories of Underdevelopment” (1968) is about an intellectual adrift in revolutionary Havana, and now here is a film in which Diego taps his brow and says, “This is a thinking head – and if you have ideas, they ostracize you.” The character of Diego is much more complex than he first appears. He is a little older than David, handsome, and well-off by Cuban standards: He lives in a small, cluttered apartment, but at least he lives there alone, and it is filled with art, books, opera recordings and even contraband scotch. He stages art exhibitions. He is widely read, sophisticated and critical of the way Cuba is run today. At one point, he takes David up to a rooftop, lets his arm sweep across Havana, and says, “We live in one of the world’s most beautiful cities. You’re just in time to see it before it collapses in s- – -.” It is a little startling to hear such lines in a movie made in Havana, by Cubans; perhaps Castro’s control of the arts is not as extreme as we think? It’s the tension between our notions of Cuba and Diego’s reckless behavior that gives “Strawberry and Chocolate” much of its fascination: Gutierrez Alea is showing us a man who takes chances with both his sexuality and his politics.

At first, of course, Diego wants to seduce David, who is a naive university student and a devout Marxist. David’s friend at school is the rigid Miguel (Francisco Gatorno), a future bureaucrat, who encourages David to return to Diego and spy on him – which is one of the reasons David returns to the intriguing flat of his new friend, but not the only one. Actually he is fascinated by the photographs and books he sees at Diego’s, and the music that’s always playing, and the fresh ideas that are churning in his new friend’s mind.

The movie reminded me of “Educating Rita” and, of course, of “Pygmalion” in the way young people, hungry for knowledge, absorb it from older ones who are in love with them; the love remains suspended while the ideas sink in. And all around are semi-documentary glimpses of today’s Havana: the ancient Detroit cars in the streets, the way color and life penetrate even dismal slums, the gloominess of Marxist orthodoxy, the ambiguity of characters like Nancy (Mirta Ibarra), who heads the revolutionary committee in Diego’s building but is much more flexible than she seems.

Sometimes the movie, based on a short story and screenplay by Senal Paz, is a little too arch in its writing. At one point David says that the atomic bomb was dropped by Truman Capote, setting up Diego’s line, “Not Capote! He was a homosexual!” My guess is that the likelihood of David even knowing Capote’s name is next to zero, and that the line shows Paz peeking through with a one-liner he couldn’t resist.

As with all statements from today’s Cuba, “Strawberry and Chocolate” can be seen reflected in many different mirrors. My first reaction was to wonder how Gutierrez Alea could get away with such pointed criticisms of his country. Yet conservative Cuban exiles in Miami have called it propaganda, precisely because it gives the impression that Cubans can safely be critical of Castro. Have it either way: The movie has real strength and charm, especially in the way it leads us to expect a romance, and then gives us a character whose very existence is a criticism of his society.