Although handsomely crafted, well-acted and made with transparently noble intentions, Roland Emmerich’s “Stonewall” is a movie that seems destined to please almost no one. Its melodramatic plot and stereotypical characters presumably were employed with the hope of drawing a mainstream audience, which, nonetheless, is likely to find both either off-putting or risible. In so doing, the film misses the chance to offer an original artistic or sociopolitical take on the 1969 riots that sparked the U.S. gay rights movement.

Watching it, you have to wonder if someone during the movie’s story conferences didn’t say, “Hey, do we really have to focus the narrative on an impossibly good-looking Midwestern farm boy who comes to New York and gets swept up in the Greenwich Village gay scene? Wasn’t that done in a film called ‘Stonewall’ 20 years ago?”

Indeed it was, and two decades on, the idea is well past its expiration date. Here, the kid’s name is Danny (Jeremy Irvine), and throughout the film we get flashbacks to the troubles back home in Indiana that drove him to New York. His dad (David Cubitt) is a stern, crew-cut high school coach who suspects his son of “deviant” tendencies, even though Danny plays football and appears straight as an arrow. Caught hooking up with the hunky guy (Karl Glusman) he’s in love with, the high school senior becomes a laughingstock at school and a pariah at home. With a mom (Veronika Veradskaya) who can do nothing but wring her hands and a little sister (Joey King) who adores him no matter what, Danny realizes he’s in an impossible situation, so he hops a Greyhound to the Big Apple.

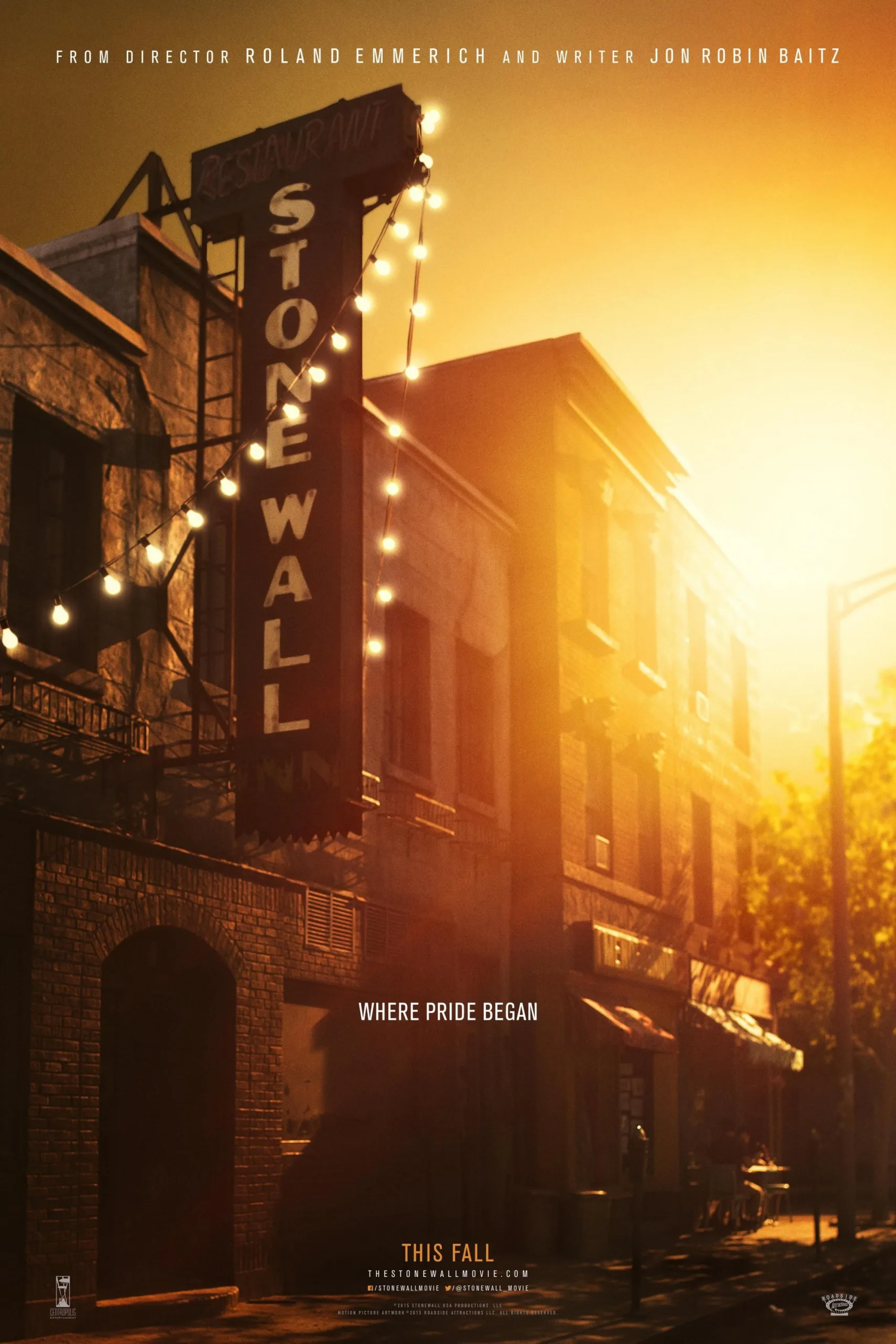

First stop once he’s there is the gay nucleus of Greenwich Village, which includes the scuzzy, Mafia-run Stonewall Inn, the only gay bar in the city that allows dancing. Here it must be noted that the film’s one area of unqualified triumph lies in the collaboration of production designer Michèle Laliberté and cinematographer Markus Förderer. Built on a soundstage in Montreal, the film’s sets—especially the gargantuan Sheridan Square re-creation—are atmospheric, impeccably executed and contribute greatly to the movie’s overall visual panache.

Since he arrives in New York bearing a scholarship to Columbia University, Danny, in addition to looking like an Abercrombie & Fitch model, is a veritable icon of white privilege next to the motley crew of gay street kids he falls in with. These include a sassy young transvestite named Ray (Jonny Beauchamp), who serves as the newcomer’s Virgil while also, of course, developing an unrequited crush on him.

As the film reminds us at every turn, these were hard times for members of the gay community. Homosexuality was illegal in much of the country and stigmatized everywhere; gays were persecuted by the government and regularly attacked by police; “out” gay culture simply didn’t exist. But there were stirrings of the political changes to come. At Stonewall one night, Danny’s asked to dance by Trevor (Jonathan Rhys Meyers), a darkly handsome activist who invites him to a gay rights meeting and, later, to live with him. Involving one of the lamest sex scenes in recent memory, the relationship between these two comes to an abrupt end when Danny sees Trevor dancing with another cute boy at Stonewall.

Playwright Jon Robin Baitz’s script contains loads of authentic details, scenes based on real incidents, and many characters modeled on actual people—almost as if he and Emmerich had a checklist of items aimed at impressing viewers with the film’s historical accuracy. Problem is, all of this authenticity is put in the service of a plot that would’ve looked stale in a 1970s TV movie, characters as clichéd as anything in vintage Hollywood, and dialogue that sometimes suggests the worst of Off-Off-Broadway.

For most of its 129-minute length, “Stonewall” mires us in the melodramatic doings of its characters, including frequent returns to unhappy Indiana. Only in its last quarter do the riots begin, and here the film’s miscues and mistakes really multiply. First, the four nights of rioting are reduced to a single outburst, which completely undercuts any hope of showing how a spontaneous bit of vandalism evolved into a conscious rebellion. Second, rather than the initially very playful and comic demonstration described by witnesses, the riot here almost instantly escalates into a huge, violent battle worthy of Emmerich disaster movies like “Independence Day.”

Third, the crucial role of the media—including negative coverage in The Village Voice, whose offices were a few doors from Stonewall—in turning the riots into a resonant public event is completely ignored. In a sense, “Stonewall” should have been much a bigger movie, one big enough to show how the struggle for gay rights was preceded by and bound up with the battles to end racial segregation and the war in Vietnam, political feminism and many other efforts at social change and consciousness raising.

At the least, though, the movie should have justified its title by showing how “Stonewall” gained its current meaning not from gay people hurling bricks through windows but from the political debates and decisions and often courageous activism that followed the night of June 28, 1969. There’s still a fascinating movie to be made from that story, one that Emmerich’s hyperbolic effusion doesn’t even begin to touch.