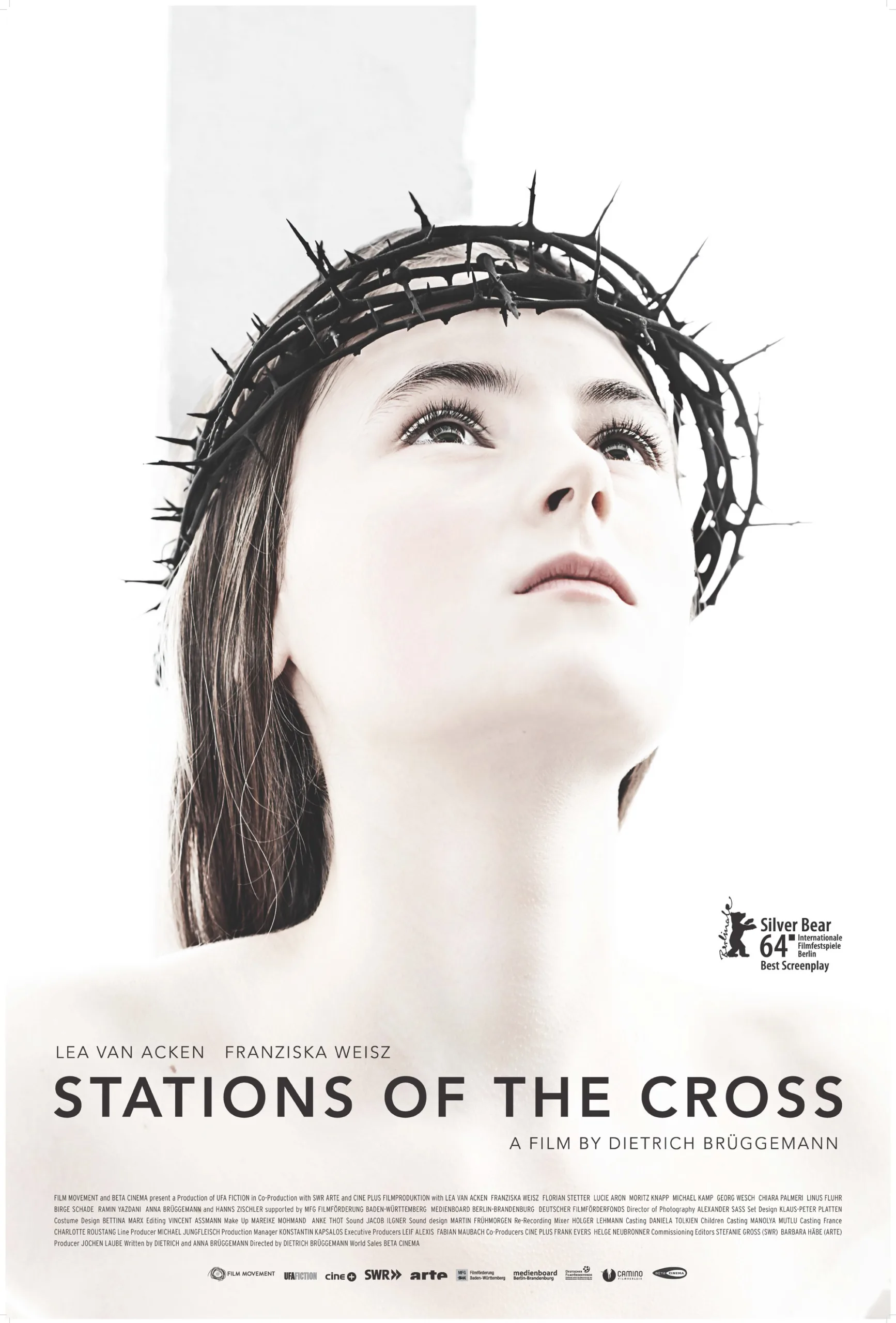

“Stations of the Cross” is an experiment in film formalism that uses strict artistic techniques to mirror the restrictions of religious fundamentalism. It is a story told in 14 shots, each one meant to represent one of the 14 stations of the cross of the title. Most of the shots are static; most of the shots are from a distance almost reminiscent of the distance of tableau of The Last Supper. The lack of close-ups, editing, etc. makes for a film that can feel stiflingly cold. It starts cold, it gets freezing—as if we are watching people on display in a museum. Despite that emotional distance, the film is carried by young actress Lea van Acken, forced to really emotionally deliver given the lack of camera tricks some actors use as a crutch.

“You alone are responsible for your souls and your neighbors.” That’s a lot to ask of a teenager. And yet that’s what the local parish priest says in the opening scene of “Stations of the Cross,” after the title card reads, “1. Jesus is condemned to death.” Is young Maria (Lea Van Acken) condemned in this opening scene? As the Priest instructs a table of teenagers that music is the devil’s tool and that they all must sacrifice not just material possessions but the evil in their hearts to allow God in, Maria clearly struggles. Left alone at the end of the scene as these teenagers head off to the spiritual battlefield of everyday life, she looks like a young person about to make a very bad decision, even if it is the name of the Lord.

In the second scene of “Stations of the Cross,” we meet another well-intentioned but misguided force in Maria’s life, her domineering mother (Franziska Weisz), a woman who constantly belittles her daughter and demeans any attempt at happiness that does not revolve around family or church. Maria is a smart, sweet, caring girl who we essentially watch destroy herself from within due to unwavering fundamentalism and a desire to please church, family, and her God, but never her own needs. People come into frame who look like they could pull Maria from the rising waters—a boy who takes an interest in her, her supportive au pair, even a doctor who recognizes inevitable tragedy—but they are pushed away by doctrine or parental force.

Maria ignores her own well-being—instructed to do so really in that opening scene when she’s “condemned to death” to help save herself and those she loves. There are early references to past illnesses that may have returned. She won’t let anyone even touch her to see if she had a fever. There’s an excellent centerpiece scene in which Maria refuses to do gym exercises at school as long as the teacher keeps playing demonic pop music (Roxette’s “The Look,” if you’re curious about Satan’s playlist). The conversation between Maria, her teacher and her classmates becomes a study in tolerance and the ripple effect of forcing religious choices upon others.

There are times when “Stations of the Cross” makes its point with a bit too much bold print and underlining, crossing over into audience abuse as we watch a mother yell at her daughter at a family dinner and the daughter cry for what feels like a lifetime. I couldn’t shake the feeling that the film is preaching to those who have already learned the inherent dangers of strict doctrine, although the reason it never sinks too deeply into that pit is the fact that Bruggemann never judges Maria or her decisions. He sure judges the religious institution that paves the road she chooses to take, but he’s balanced enough to never judge her for going down it.

In the end, the formalism of “Stations of the Cross” wouldn’t work at all without the work of van Acken, a very talented young lady who’s not only in every scene, she’s often all there is to every scene. “#5” is just a profile shot of Maria in confession, something that would terrify some young actresses. Van Acken’s smart, subtle decisions keep Maria from becoming little more than a symbol or even the caricature she could have become. Even when “Stations of the Cross” becomes almost overwhelmingly depressing, we can’t turn away from Maria. It is in the humanizing of her plight that “Stations of the Cross” finds its power. It’s a hard movie to leave behind. As it should be.