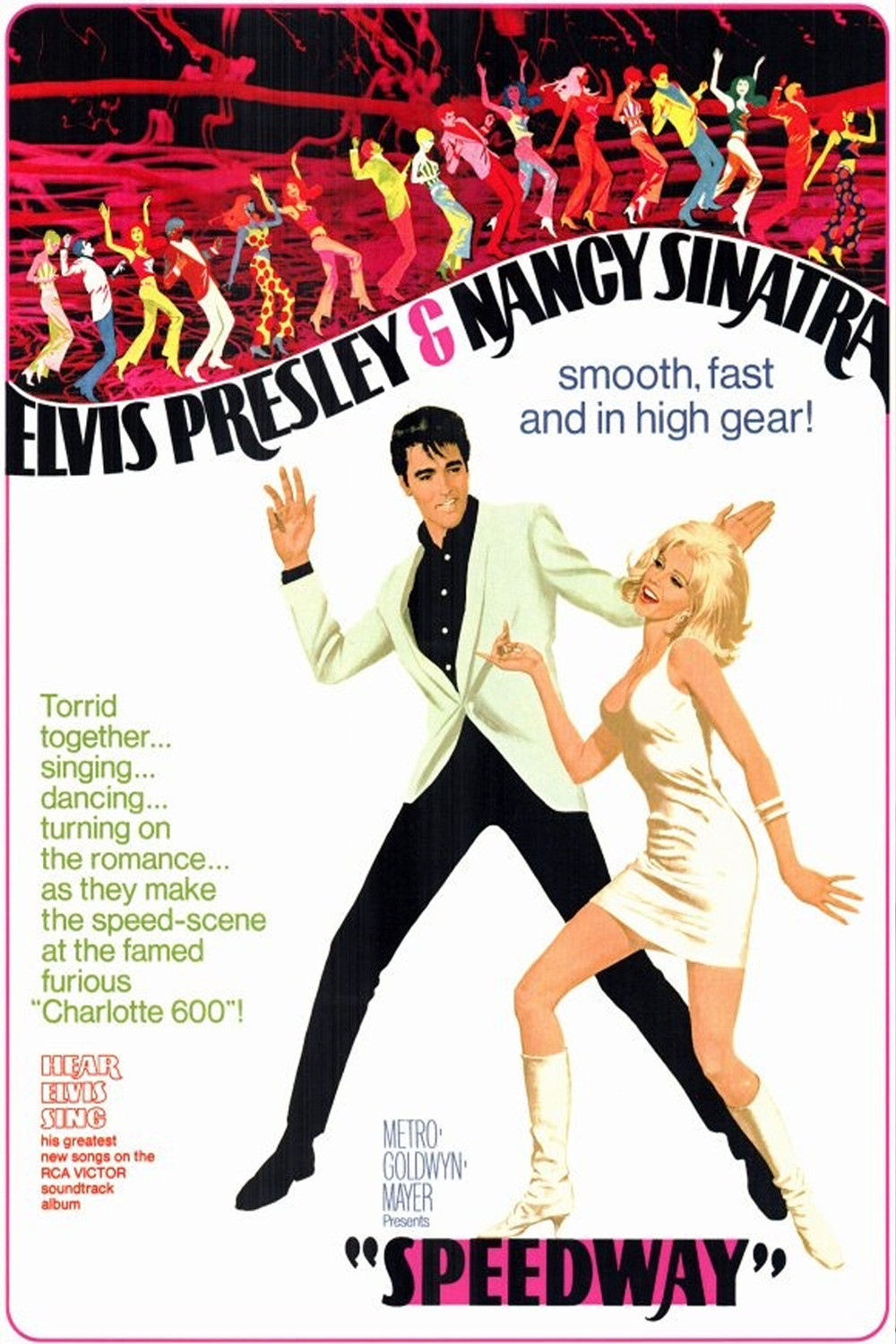

You may not believe this, but I was inspired to see Elvis Presley’s “Speedway” because of this week’s Essay in Time magazine. There were other reasons, too. I hadn’t seen an Elvis movie since last summer’s “Easy Come, Easy Go,” and after a week of war movies (Mexican, Second and Vietnam) the idea of a nice, relaxed, simple musical held allure.

Time’s Essay is entitled “The Late Show as History.” It points out that the 13,000 old movies now providing TV’s late shows are “America’s National Museum of Pop Art, the biggest repository of cultural artifacts outside the Smithsonian.”

Time is right. The old movies contain the attitudes, prejudices, hopes and dreams of earlier years. They recall the hunger for money during the Depression, the era of the great stars, and the unashamed B Western: “Golly, Mr. Autry,” sighs Pat Buttram, “you sure do sing purty.”

Just the other night, for example, Chicago saw Spike Jones and Buddy Hackett in “Fireman, Save My Child,” a 1954 comedy described by The Sun-Times’ TV Prevue as a “false alarm.” So it was. But where else, I ask you, could a younger generation learn who Spike Jones was? Or that Buddy Hackett hasn’t changed his style in 14 years? These are discoveries not to be sniffed at.

“Speedway” is the late show of 20 years from now, I suppose. What will it tell the insomniacs of 1988 about our society? For one thing, they will probably wonder why we considered Elvis a sex symbol. He is as respectable on the screen as Dick Powell ever was, and his recent movies hold no hint of the swivel hips my generation remembers from the Ed Sullivan shows of 1956.

Viewers will also find a catalog of the recreations and material possessions prized in 1968, especially by Southerners. Elvis’ films are quite successful in the South, and “Speedway” seems to have been made with that market in mind.

Stock-car racing is far and away the most popular Southern sport (see Tom Wolfe’s “The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby”). So in “Speedway,” Elvis races a Barracuda around the Charlotte Speedway, lives in an expensive mobile home, drinks pop and keeps his hair combed.

“Speedway” also reflects the ground rules of courtship established in old Ozzie and Harriet shows. Elvis is excessively proper in behavior with his various dates (one of whom is Beverly Hills, the Hollywood stripper whose charms rival Brigitte Bardot’s, and another of whom is Nancy Sinatra, whose charms do not).

There is a lot of coyness. “You locked us in here on purpose,” Nancy pouts, and Elvis gets his extra key to prove he didn’t mean to. Meanwhile, Nancy climbs out the trailer’s window, which seems excessive under the circumstances. But maybe not. At least one of the girls in “Speedway” is convinced by tape-recorded animal roars that the lions have escaped from the zoo, and that Elvis’ trailer is the only safe haven.

And so it goes, with Elvis buying a station wagon for a poor family, and Elvis arguing with the tax man, and Elvis climbing into his Plymouth, and Nancy Sinatra still desperately trying, at this late stage of her career, to sing.

“Speedway” is pleasant, kind, polite, sweet and noble, and if the late show viewers of 1988 will not discover from it what American society was like in the summer of 1968, at least they will discover what it was not like.