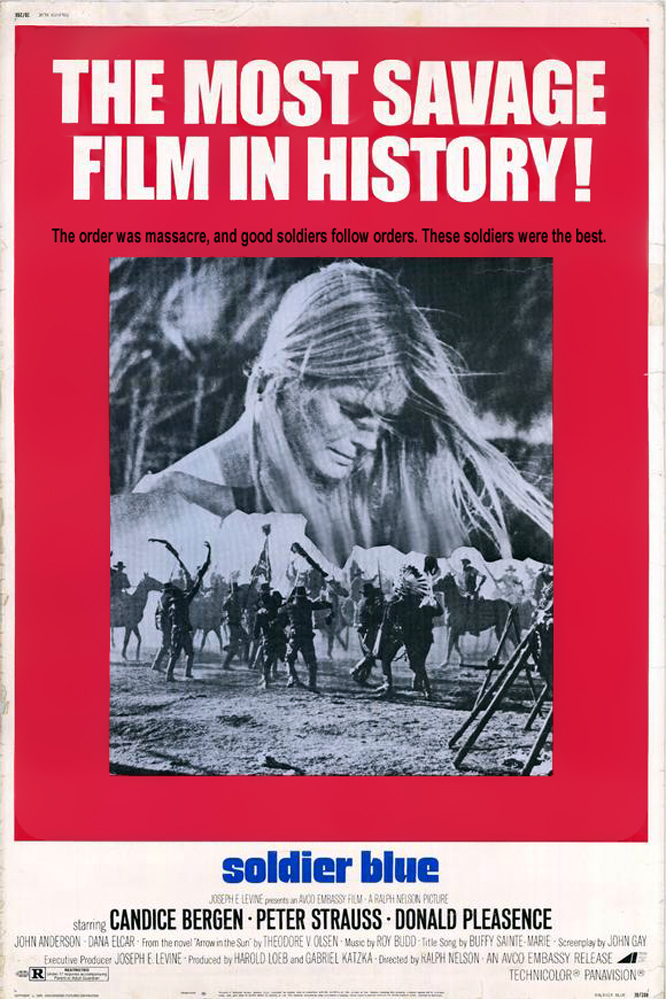

Why, its ads asked, does “Soldier Blue” show, “in the most graphic way possible, the rape and savage slaughter of American Indians by American soldiers?” Because it’s true, the ads replied, and “now more than ever is the time for truth.”

Now more than ever is also the time for violence in movies, a point that hasn’t been lost on the makers of “Soldier Blue.” “Soldier Blue” is indeed savage, but it wears its clock of “truth” self-consciously. It is supposed to be a pro-Indian movie, and at the end the camera tells us the story was true, more or less, and that the Army chief of staff himself called the massacre shown in the film one of the most shameful moments in American history. So it was, and of course we’re supposed to make the connection with My Lai and take “Soldier Blue” as an allegory for Vietnam.

But that just won’t do. The film is too mixed up to qualify as a serious allegory about anything. And although it is pro-Indian, it is also white chauvinist. Like “A Man Called Horse,” another so-called pro-Indian film, it doesn’t have the courage to be about real Indians. The hero in these films somehow has a way of turning out to be white.

In “A Man Called Horse,” Richard Harris was your average English aristocrat, but damned if he couldn’t out-hunt, out-fight, out-shoot and out-lead all those Sioux, who made him their chief out of pure gratitude. And now in “Soldier Blue,” Candice Bergen is the white girl from New York who “understands” Indians and makes liberal speeches and goes back to warn the tribe when the Cavalry is coming. Nobody who looks authentically Indian gets very close to the camera.

Anyway, “Soldier Blue” is about how Candice Bergen and Peter Strauss survive an Indian massacre and try to walk overland to Fort Reunion. They have the usual adventures along the way; the movie is similar in form to “Two Mules for Sister Sara,” “The African Queen” or any of those movies where a man and woman have to team up to face the wilderness (and fall in love). Miss Bergen’s dialogue is so fashionably contemporary that it sounds funny coming from a character who presumably lived 100 years ago. Strauss is unconvincing as the soldier; he keeps making mistakes and getting set straight, like those emasculated husbands in TV situation comedies.

After a sufficient number of adventures, separated by a sufficient number of “significant” speeches by Miss Bergen, the couple get back to camp and a second story begins. It’s about the massacre, and the massacre is such a bloody business that the movie simply can’t support it. So we sit there embarrassed at the clumsy way director Ralph Nelson reaches for significance. Nelson is an awfully good director when he’s on (“Tick … Tick … Tick,” “Lilies of the Field,” “Charly“). This time he’s way off.