“Narcissus, at high tide, escaped without wings.”

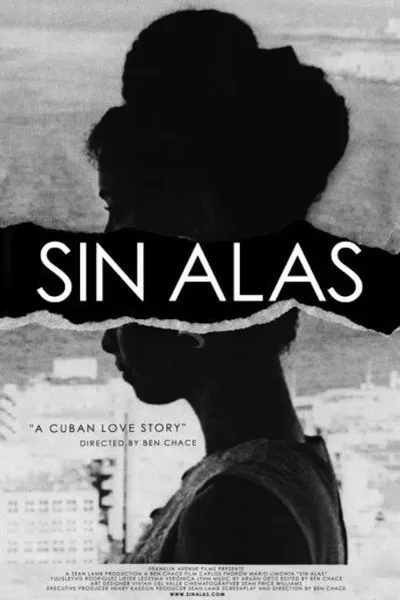

Those are the final words of 20th century Cuban poet Jose Lezama Lima’s “Muerta de Narciso,” a poem excerpted throughout “Sin Alas,” writer/director Ben Chace‘s impressive feature debut. The first American film to be shot in Cuba since 1959, “Sin Alas” is about memories and dreams, flashbacks and continuums, fragmented timelines and piled-up detritus. It’s about the way light looks in Havana in the morning, the way echoes carry through doorways, the way the surf crashes over the sea wall. It’s about rambunctious street life, music and voices and eccentric characters, playing out against the backdrop of gorgeous crumbling pre-Revolution buildings, all of which still have stories to tell, messages to pass on. “Sin Alas” has a lot going on, both plot-wise and stylistically, and it often gets quite theatrical, but the overall effect is that of a pure and beautiful simplicity. There is nothing in the way between the story and its impact.

Luis Vargas (Carlos Padrón), a 70-year-old former arts journalist, opens the newspaper one morning and sees an obituary for a once-famous dancer, Isabela Munoz (Yulisleyvís Rodrigues). Back in 1967, Luis and Isabella had a brief but very intense affair. News of her death stirs the depths of his soul, memories—all fragmented and hallucinatory—crowding before his eyes. He has been dreaming of Isabela, the same dream every night, and in the dream, a song is playing. He does not know what the song is and he tells his friend Ovilio (Mario Limonta) about it. The two friends set out on a quest to find out the name of the song. (This musical motif, composed by Robert Pycior, recurs throughout “Sin Alas,” sometimes played with mournful cellos, sometimes with pounding bongos underneath, sometimes with single piano notes sounding like a child’s music box. Music is not used in “Sin Alas” as lazy filler or to manipulate audience emotions. The music is sweepingly dramatic: it’s an old-fashioned score.)

“I need to get this melody out of my head so I can rest,” says Luis to Ovilio. That quest leads him down pathways of memory that he might have wished to avoid, but once the floodgates open, there’s no stopping it. Luis grew up in a wealthy family of sugar-planters, and his parents fled Cuba when Castro took over. He, a young man of 20, stayed behind. There are mysteries in his childhood, things glimpsed when he was a boy, not understood.

Ben Chace and his cinematographer, Sean Price Williams, have chosen to use different color schemes for each separate era. This might sound cliche, but it isn’t in execution. The color schemes are threads through the labyrinth of associations, locating the different spots on the timeline as they come in and out of focus. Luis’ childhood is in crisp, almost alienating black-and-white, sunlight bursting through the frame, bringing not clarity but dizzying reflections and refractions. This is no golden-hued nostalgic past. This is something else entirely. Luis and Isabela’s 1967 affair (with Lieter Ledesma Alberto as the younger Luis) has a glamorous 1960s palette, all sea-greens and silvers and pinks, passionate and yet somewhat cold, torrential rain pouring on the windshield, Isabella’s silvery nail polish gleaming against a cut-glass tumbler. The paranoia of Castro’s Cuba is intense in the 1960s sequences, and the style reflects that reality. In the current day, life on the street may be more relaxed, but that paranoia remains: open doorways, labyrinthine stairwells, windows peering down on the residents from above.

In “Listen Up Philip,” “Christmas, Again,” “Heaven Knows What,” “Queen of Earth,” and now “Sin Alas,” Sean Price Williams shows he is one of the most gifted cinematographers working today. He’s wonderful with fluid camera movements and intuitive closeups. He can “catch” a mood, or a type of light, or the space between people, in a way that tells 90% of the story. The current-day Havana-street scenes in “Sin Alas” have a lot in common with the street photography of “Heaven Knows What,” Williams’ camera seeming to be everywhere at the same time, not missing a beat. But the flashbacks and dream sequences in “Sin Alas” are surreal and eerie, with elongated shadows stretching across rooms or up gigantic empty marble stairways. Along with the score, Williams’ work brings out the depth of Chace’s story, its potentials, its universality. This is not a “slice of life” movie. It’s a “meditation on life” movie. “Sin Alas” is emotional and dense, thought-provoking and intelligent, and it’s all held together by music, Lima’s poem, colors, sounds.

Ingmar Bergman (“Wild Strawberries,” in particular) is a clear influence on “Sin Alas”: dreams bleeding into waking life, the past flowing into the present, as an old man close to death goes on a “journey,” coming to accept the liquidity of time and his own mortality. The past doesn’t just contain the story of “what happened,” the past also holds Luis’ various younger selves, and all of the once-vibrant people he used to know, people now dead and gone.

“Narcissus, at high tide, escaped without wings.” In Spanish, “without wings” translates to “sin alas,” and throughout this beautiful film, characters try to fly with clipped wings, develop wings they never knew they had, or accept the fact that the time for “escape” is long past. However bleak this may sound, “Sin Alas” is not about hopeless people living hopeless lives. Everybody wants something, and everybody tries to get what they want. Life is vibrant and sad, tough and poetic, lonely and claustrophobic, simultaneously. The past has been severed from the present, with a sense of dislocation the result. Time is speeding up, and at points, it is as though everyone is waking up from a dream. Nobody knows which way things will go. (When asked why he didn’t go to America with his parents, Luis says, “I wanted to see where all this was going.”) Each character trembles on the edge of an abyss. Narcissus escaped “without wings.” Can they?