If there’s anything worse than a laborious fable with a moral, it’s the laborious fable without the moral. The more I think about “Simon Magus,” the less I’m sure what it’s trying to say. It leads us through a mystical tale about Jews, Poles and an outcast who takes orders from Satan.

Both groups would like to build the local railroad station, but the outcast, a mystic, has visions of these very tracks being used to take Jews to the death camps. Does that mean it doesn’t matter who builds the station, because the trains will still perform their tragic task? In that case, what’s the story about, except bleak irony? The movie takes place in 19th century Silesia, bordering Hungary and Austria. Some 20 Orthodox Jews have a small community near a larger gentile town. The new railroad bypassing the town has created hard times for everyone. A Jew named Dovid (Stuart Townsend) wants to build a station and some shops, which will help out the woman he loves, a widowed shopkeeper named Leah (Embeth Davidtz). A gentile named Hase (Sean McGinley) also wants to build the station. The land is controlled by the squire (Rutger Hauer), a dreamy intellectual.

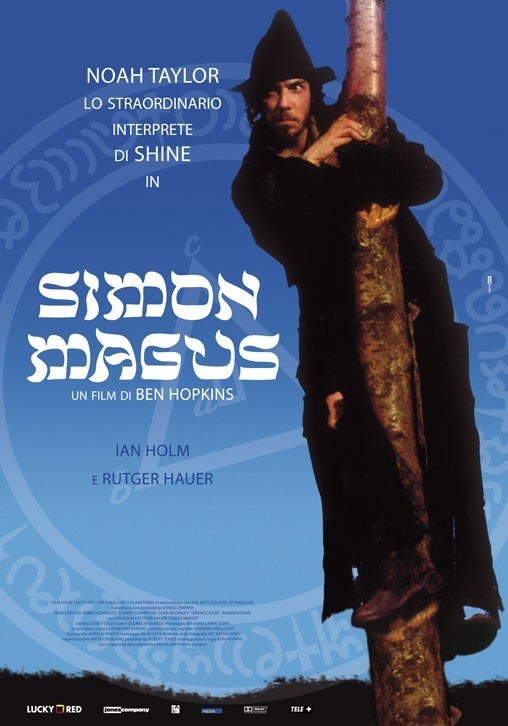

This would be a story about anti-Semitism and real estate, were it not for two other characters. Simon (Noah Taylor) is a Jew who is scorned by his own community because of his crazy ways. From time to time, as he makes his way through the gloomy mists of the town and forest, he is approached by Sirius (Ian Holm), who seems to be the devil. When Satan appears in a movie, I always look around for God, but rarely find him; it’s usually up to the human characters to defeat the devil. In this case, Simon’s visions of the death trains perhaps suggest that God is taking a century off.

The non-supernatural side of the story involves the good Dovid and the bad Hase (a villain so obvious he lacks only a mustache to twirl). Both want the squire to make his land available. The squire, a lonely and bookish man, wants intellectual companionship, someone to read his poems and keep him company around the fire on long winter evenings. Dovid, a talmudic scholar but not otherwise widely read, takes lessons from Sarah (Amanda Ryan), who is up on poetry. At one point, she and the squire get into a literature-quoting contest.

“Simon Magus” creates a sinister subplot in which the evil Hase tries to trick Simon into taking a box with a Christian baby inside and hiding it in the rabbi’s house, so that a mob can discover it as proof that the Jews plan to eat it. Simon responds with intelligence that surprises us, but what good purpose does it do to resurrect this slander? Most people now alive would never hear of such ancient anti-Semitic calumnies were it not for movies opposing them. Does Ben Hopkins, the writer-director, imagine audiences nodding sagely as they learn that baby eating was a myth spread by anti-Semites? Isn’t it better to allow such lies to disappear into the mists of the past? The story is resolved along standard melodramatic lines, and good (you will not be surprised to learn) triumphs. Yet still those death trains approach inexorably through Simon’s visions. The papers are filled these days with stories of Polish villagers who rounded up their local Jews and burned them alive. What difference does it make who builds the train station?