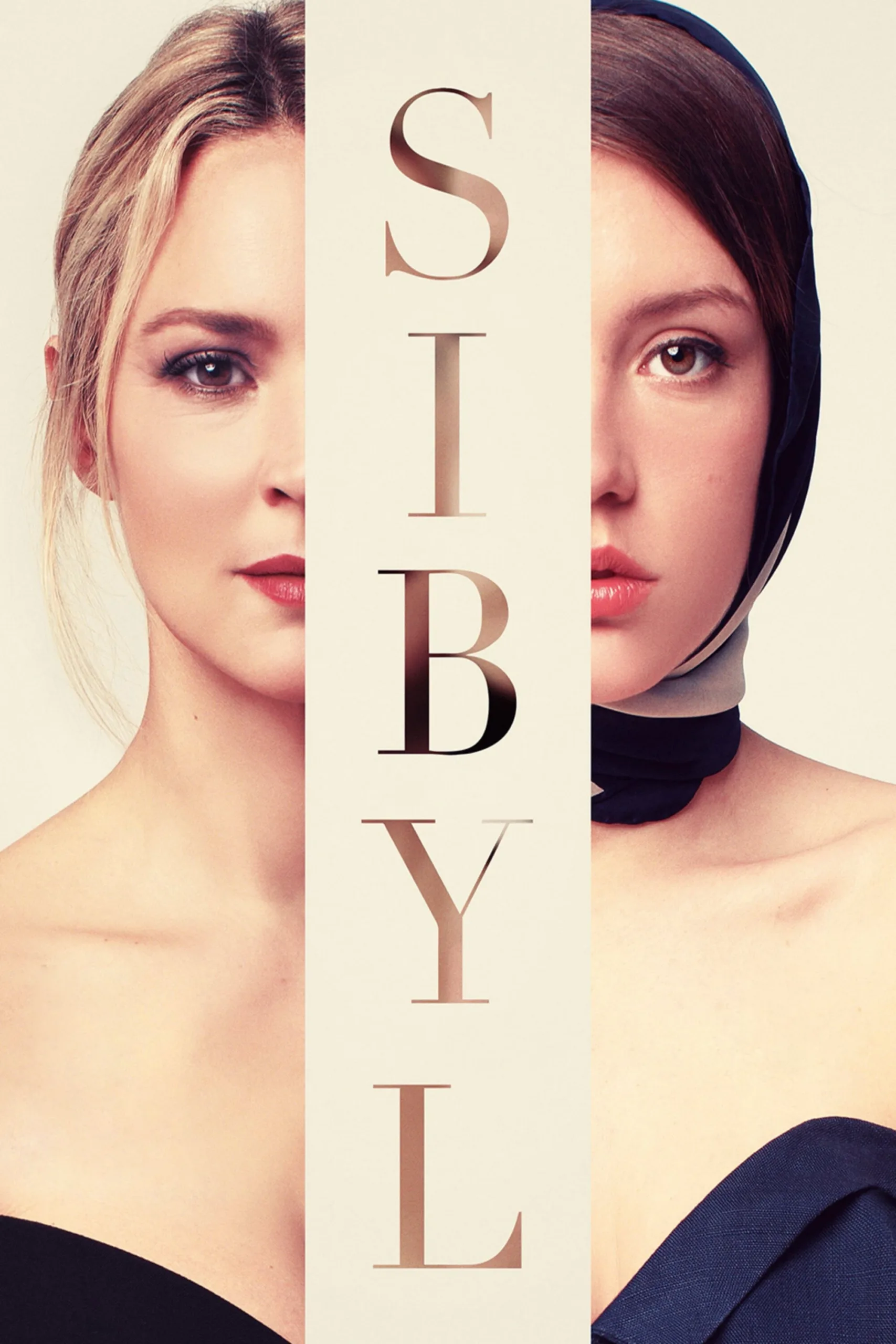

In the hybrid story that we conceive as our reality—part truth and part subjectivity—we are also versatile actors giving dozens of performances that influence the lives of others. We manipulate and are in turn manipulated by loved ones, strangers, and acquaintances. French writer/director Justine Triet’s “Sibyl” wraps these observations in an elegant meta tale exploring emotional engineering on the page, on set, and in the eponymous mastermind’s personal storyline. Rich in impulsive sensuality and knowing humor, the film captivates even as it stumbles through too many subplots. It’s a tad convoluted but never dull.

“In my dreams people unmask me,” says Margot (Adèle Exarchopoulos), a novice actress caught in a professional love triangle. She confesses this in her first meeting with an attentive Sibyl (Virginie Efira), a psychologist on her way out of the profession to write a novel. Margot is afraid of being seen for the broken person she believes she is, as opposed to the public persona she’s tried so diligently to confect. Exarchopoulos operates in heightened, raw distress for most of the running time, drowning Margot in tears of desperation and rage.

Ethics be dammed, Sibyl surreptitiously records their sessions to lift Margot’s real-life turmoil from her first major production and enliven her manuscript with the detailed, almost literary descriptions of the affair she’s having with her famous co-star Igor (Gaspard Ulliel), who’s in turn dating the movie’s director Mika (Sandra Hüller). Note the stellar ensemble cast featuring more than a handful of Europe’s most gifted thespians including Paul Hamy as Sibyl’s neglected husband Etienne.

A recovering alcoholic with plenty of baggage, Sibyl has shifted her addictive tendencies to the creative process. She’s found an exhilarating, even perverse sense of control in molding Margot’s sorrow for personal gain. It’s in her book’s best interest to take what the ingénue says at face value, rather than question the validity of the melodrama she depicts. Soon, the therapy sessions transcend the limits of patient-mental health professional boundaries when Margot asks for Sibyl’s advise on whether or not to have an abortion.

There’s a fascinating mutual investment in their odd friendship that doesn’t necessarily rely on a power imbalance. Instead of one taking advantage of the other, Margot and Sibyl seem to have an unspoken understanding that they are both embodying what the other needs at this point in their tumultuous existences.

While Exarchopoulos’ part requires consistency to convey her perpetual misery, Efira layers facets upon facets of Sibyl from one sequence to the next. Her fragmented personality as a concerned mother, an unscrupulous artist, an ardent lover, or a drunk staggering through a party exemplifies the multi-verse inside us all depending on our audience. It’s riveting to witness Efira transition from levelheaded to disturbed, passing through several frenzied modulations.

Triet’s vivid writing and skillful execution play with realism and over-dramatization. Her direction manages to maintain the atmosphere at that intersection, with certain beats reading as literature in their exaggeration while others are stripped down. Still, despite the great intensity of the piece, flashbacks to her time with ex-lover Gabriel (Niels Schneider), her relationship with her sister, or even her arguments with her own therapist, convolute an already heavy collection of characters and situations. At some point the murky timeline, which attempts to fold in all these past traumas and details, suffers from its own ambition.

Sibyl has willingly infiltrated this interpersonal debacle, and incrusts herself further in it when she agrees to travel to the Mediterranean island where Mika is shooting under the pretense of being there to support Margot and mediate between the three parties. Hüller accounts for many of the sly chuckles with her deliberately over-the-top turn as a filmmaker on the verge of a breakdown. It’s also in this second half that cinematographer Simon Beaufils shines brightest when lensing scenes within scenes in the idyllic place.

“Keep the drama fictional,” demands Mika when Margot uses a scene to repeatedly unleash her disdain for Igor. But the distinction between the synthetic heartbreak they are putting on display and the underlying animosity between them off-camera becomes increasingly difficult to pinpoint. The artifice of acting, an artful form of lying to generate a reaction from the viewer, continuously dominates Triet’s screenplay as a key theme of this puzzle.

Unable to elicit a passionate take from her leads, Mika despairs and Sibyl briefly takes on the role of the director. Triet once again switches the filter through which the protagonist sees the romantic strife she’s now a part of—always at a distance, without much empathy, even when it’s unfolding in front of her.

As the doomed location shoot approximates its nadir, a scene shows Sibyl reciting Margot’s lines, not from Mika’s text but from their private conversations, as if they were sides for an audition. It’s a brilliant encapsulation of the film’s self-referential through-line. Caught in a parade of lies—including her own—that obscure all sense of veracity, Sibyl finds it easier to reenact another person’s vulnerable moments than confronting her own. The illusion of someone else’s anguish is at least bearable. Once the adventure into filmic deceit is over, Sibyl can’t detach storytelling from flesh-and-blood interactions. Approaching her destiny as if it were a figment of the imagination may be the only way to cope with how powerless she is when trying to rewrite it.

Now playing in virtual cinemas.