Kim Longinotto’s documentary “Shooting the Mafia” is not for the squeamish—it matter-of-factly brandishes numerous images of dead bodies on the ground, sometimes accompanied by pools of blood. Sometimes they’re slumped over in chairs, or lying face down. The corpses, like that of a teenage boy, often take up only the bottom third of the frame, as if they’ve become a natural part of the environment.

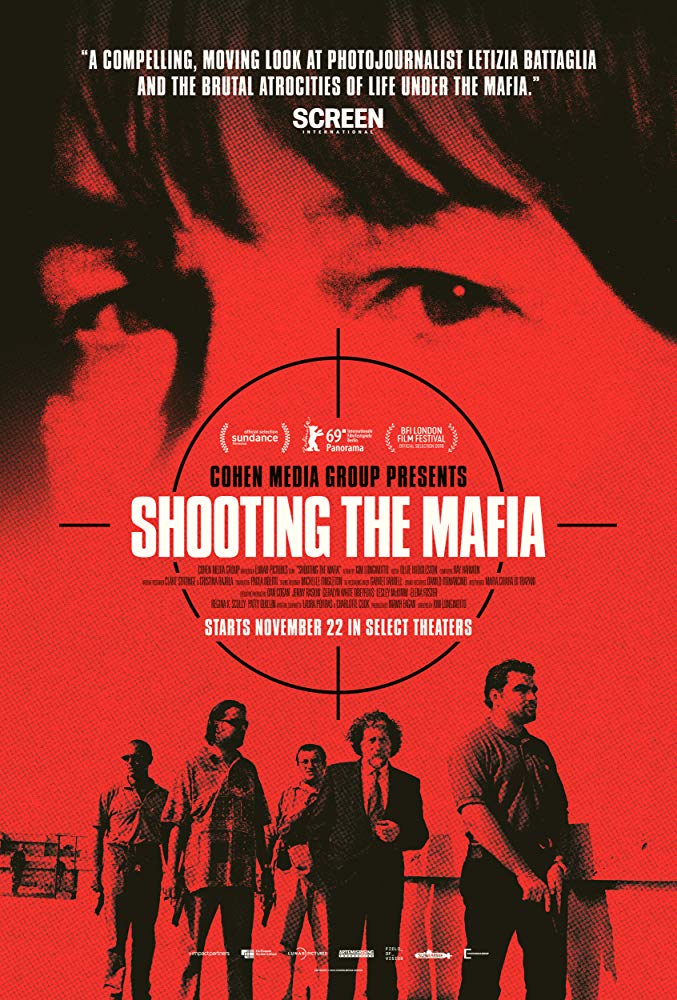

These photo subjects are the targets of Mafia slayings, and Italian photographer Letizia Battaglia has documented countless deaths. As it emphasizes both the photographer and the photo, the compelling “Shooting the Mafia” features a great deal of these snapshots, in a manner that is even more melancholy than it is disturbing.

Battaglia was the first woman photographer to work for a daily Italian newspaper, and her plan was not originally to photograph the Mafia. But three days into her work, she witnessed her first murder. It started a collection that is hard to explain, but necessary. “I could tell my own story,” she says. “I could feel it rather than understand it.”

Her life also put her in the vicinity of those deep in the Mafia wars. She talks about her interactions with ghoulish Mafia bosses, or the pain she felt when a heroic judge was murdered. The word “fear” pops up often in the documentary, emphasizing how Battaglia went against the environment, initially as a woman in a world of men, and later even more so as a journalist surrounded by bloodshed and turmoil.

The story has a clear impact on her; such dedication comes from a stunning idea of compassion, but also courage. “Photographing trauma is embarrassing,” she notes. But later adds, “It’s the photos I never took that hurt me the most … I miss them.”

Battaglia appears in various candid interviews, her hair sometimes a spunky pink, and in other occasions light orange. Longinotto often seems to catch her while she’s sitting on a bed, or passing by time with a cigarette in hand. These moments are in welcoming juxtaposition to her disturbing images, especially when watching Battaglia atone for the difficult familial or romantic relationships that came with such a line of work. In one striking yet unassuming snippet, Battaglia sits hunched over a table looking over at an old partner, who is also hunched. They talk openly about their relationship; the camera placed as if we were eavesdropping on two people Having A Moment. It all helps give the movie a strong personal core, to then elaborate on the sacrifices of her disturbing work, and always humanize the artist.

“Shooting the Mafia” does have one key aesthetic force working against it—other movies, as Longinotto keeps referring to film clips when trying to depict something. So when the voiceover talks about kissing, there may be old black and white footage of a couple doing just that; the same goes for when someone tells of a gunfire, and an old clip is used to show it. As these clips are from Italian movies (like Francesco Rosi’s “Salvatore Guiliano,”) maybe some subtext is lost in translation. Here, they play like on-the-nose visual storytelling devices.

What’s interesting about the movie, but later a bit frustrating, is in how it balances its candid statements with the magnitude of Italy’s Mafia violence history. Battaglia becomes a bit of a secondary character as Longinotto spends ample time providing backstory about when the Mafia reacted against a mass incarceration, killed certain Italian officials, and then the unrest that followed. Possibly because the movie doesn’t have enough material to talk about just Battaglia for feature length, “Shooting the Mafia” goes into these details that are illuminating but also feel like they’re from another movie.

In the end, “Shooting the Mafia” is about recognizing Battaglia as a woman of immense bravery and unflappable individuality. She has seen a great deal of sadness in the world, and captured it in a way that combines art, journalism, and activism. “Shooting the Mafia” aptly conveys Battaglia’s many layers, while exemplifying the power in not looking away.