‘Separate Lies” opens with an event so sudden it is over before it can be registered; only later do we discover that a man was knocked from his bicycle by a speeding car, which didn’t pause. The man was killed. It happened on a lane near the country home of a London lawyer, on the afternoon he and his wife invited some neighbors for drinks. The dead man was the husband of their housekeeper.

The movie is not so much about the solution to this crime, as about the ethics involved in taking responsibility. If you can, should you get away with murder? What if you did not intend to kill — what if it was an accident? The man is dead. Should you be made to suffer? Many people have one answer to these questions when a stranger is involved, and another when it touches them personally. Not even a hanging judge wants to hang.

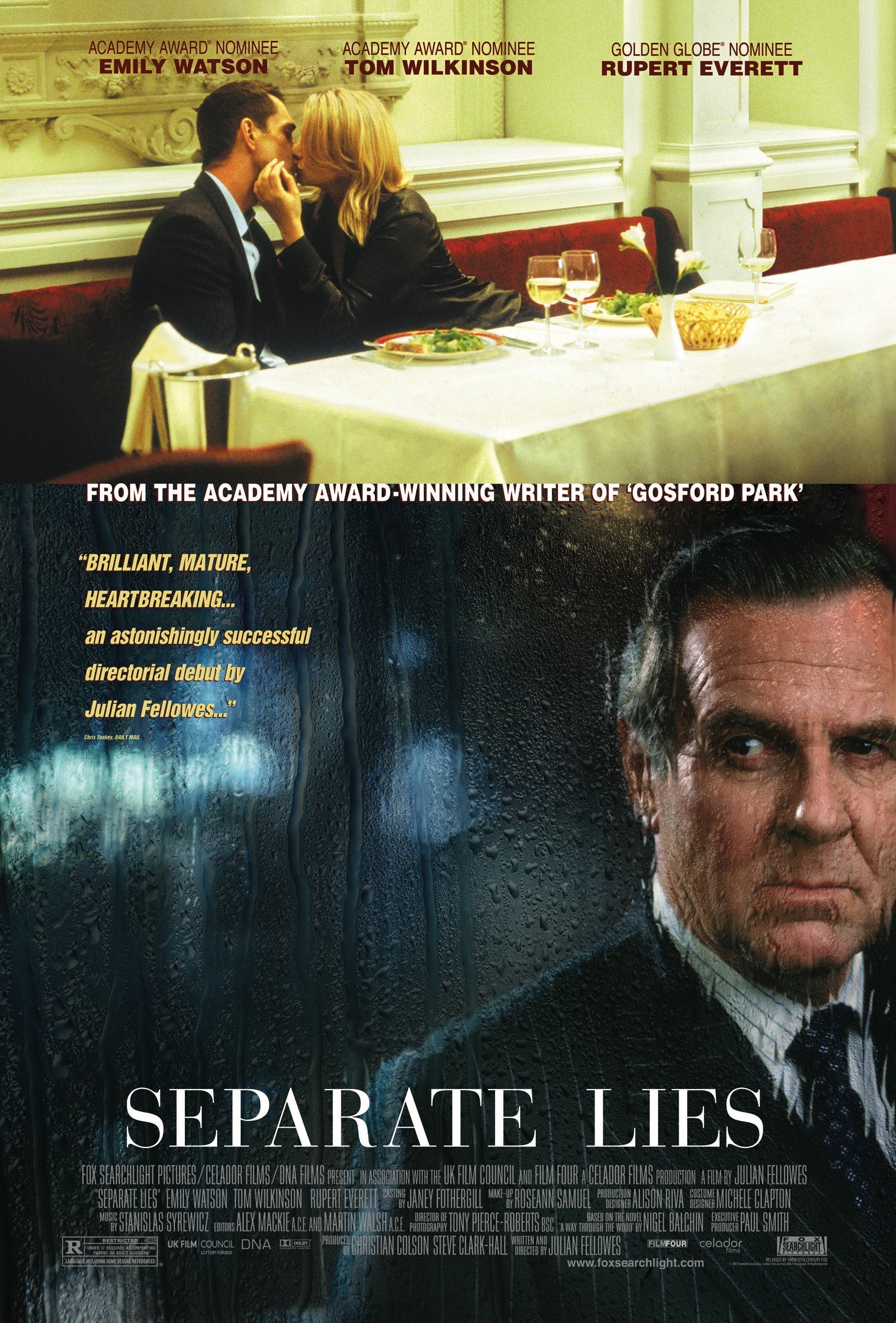

“Separate Lies” stars Tom Wilkinson as James Manning, the lawyer, and Emily Watson as Anne, his wife. Their marriage seems happy enough. He’s one of those lawyers who specializes in making powerful clients more powerful. When it comes to matters of right and wrong, he likes to think of himself as inflexible. His wife is accommodating and dutiful and likes the life they lead, the house in London, the Buckinghamshire hideaway.

In the village a remembered face has reappeared. This is William Bule (Rupert Everett), son of a leading local family, recently returned from America, indolent and insinuating as he plays cricket on the village green. He catches Anne’s eye, and it is because of him, really, that she tells her husband they should have neighbors over for drinks. Everett plays Bule as a man detached and arrogant, dismissive of conventional values, attractive to women because he doesn’t seem to care how they feel about him one way or the other.

James Manning, on the other hand, is serious and responsible and we catch glimpses of the idealistic undergraduate. Wilkinson, who often plays ordinary men, here emerges as a sleek London figure, no stranger to the shirtmakers of Jermyn Street; he has the impatience of a man who is always having to explain things to people who do not have his standards. Anne may be one of those people; perfect as she seems, she feels she never quite comes up to his mark.

Now there is the matter of the dead body in the grass beside the lane. There was a witness, as it happens: Maggie (Linda Bassett), whose husband was killed. She saw the car and might be able to identify it. Or perhaps not. Maggie knows William Bule, too; she worked for his family until she was dismissed. It was Anne who gave her a new start in the village. When the police constable comes around, he will want to talk to all of these people, not because they are suspects, but because they might (as the British so carefully word it) be able to assist the police in their inquiries. Certainly Anne is not under suspicion: “One person not driving to a party,” her husband observes, “is surely the hostess.”

The unfolding of the plot I will leave for you to discover. The story, based on a 1950 novel by Nigel Balchin titled A Way Through the Wood, could as easily have been told by Agatha Christie, if the focus is on the whodunit aspects, or by Georges Simenon, if we know whodunit but want to know how they feel about it, and how their feelings change as they discover more details. The movie’s director, Julian Fellowes, takes the Simenon approach, although some of his moments of revelation could take place in an Agatha Christie drawing room where a word or two rotates a crime into a new dimension.

Fellowes, who has worked mostly as an actor, won an Academy Award with his screenplay for Altman’s “Gosford Park” (2001). There, as here, he is fascinated by the way class lingers on in Britain after its time has allegedly passed; how fierce loyalties and resentments are exchanged between upstairs and downstairs. The way he handles James and Anne is a case study in British manners: There is the sharp outburst, to be sure, and even the f-word, used for effect by a person who doesn’t talk that way. But there’s none of the screaming and weeping and acting-out of American domestic drama; James and Anne would rather be reasonable than be in love, because there’s less chance for embarrassment that way. At one point, when a possibility is suggested, James curtly replies: “I’m afraid that’s a little too Jerry Springer for me.”

“Separate Lies” reminded me of Woody Allen’s “Crimes and Misdemeanors.” Its characters are above reproach — from themselves. Others deserve justice, but we deserve compassion and understanding. This is hypocrisy, but so what? Do onto others as you would not have them do onto you. “Separate Lies” is only seemingly about the portioning of blame. It is actually about the burden of guilt, which some can carry so easily while for others, it is intolerable.