At about the midway point in “See You in the Morning,” there is a scene set in a group therapy session – one of those groups where all the statements seem to begin with the words “The trouble with you is. . . . ” The women in the group have trouble with men, and the men have trouble with women, and the issue is usually Trust, although it can also be Dependence or even Childhood Loss. The fears expressed during this group seem to radiate out into the rest of the screenplay, infecting a relatively simple story with psychological jargon.

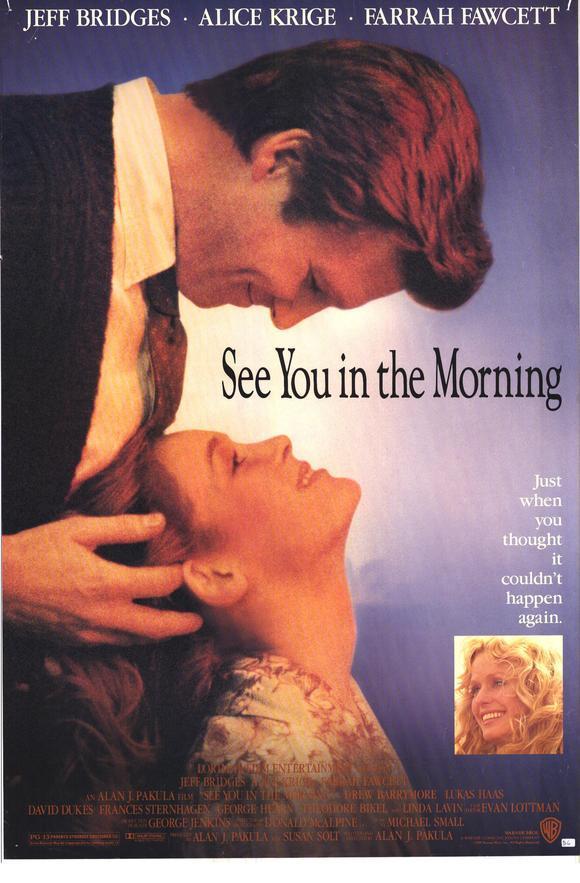

Perhaps that is the point. The hero of the story is Larry Livingstone (Jeff Bridges), a psychiatrist. He is the very model of a modern, sensitive male, who is able to see both sides of every issue so thoroughly that he even discusses his own mistakes with a certain bemused wonder. At the outset of the movie, he is married to a model (Farrah Fawcett) and lives happily, it would seem, with her and their two children. Then she says they need to have a talk.

We meet another family, the Goodwins, also with two children.

He is a concert pianist who is faced with the paralysis of one of his hands. She has devoted her life to supporting him. One day his hand betrays him in the middle of a concert, and two years later, we learn, he kills himself. Both this death and the divorce proceedings of the Livingstones are kept offscreen, while the film flashes forward three years to a meeting between the psychiatrist and Beth, the pianist’s widow (Alice Krige).

They fall in love. Well of course they do. They’re both in need, both lonely, and as he walks her home through the rain they discover, as people always do in the movies, that getting wet together is one of the most romantic things that can happen to you. There is a marriage, and then the movie settles in for the long haul, to consider Larry’s problems as the new stepfather of Beth’s kids, Cathy (Drew Barrymore) and Petey (Lukas Haas).

Cathy seems more or less normal. Petey has a habit of practicing his cello far into the night, “as if,” his mother says, “he feels that he somehow caused his father’s death by not practicing enough.” When Beth is sent to Russia to photograph a concert tour, Larry is left with the two kids and tries his best to understand them and relate to them in an intelligent and sensitive way. Of course he fails, intelligently and sensitively. And when Beth and Larry get that worked through, Larry’s first mother-in-law grows ill and dies. Alone with his first wife in a northern cottage, he grows foolishly nostalgic for what they once had together, and attempts to have it again, but is betrayed by his equipage.

Of course his near-miss must be confessed immediately to Beth, but in terms so abstract and analytical that he seems to be diagnosing, not castigating, himself. And in the treatment of that scene I finally began to discover that I had been through enough therapy. If a movie is going to alternate between simple human spontaneity and tortured self-analysis, then it had better have a point of view toward one or the other. To use them as a sort of sweet-and-sour of the soul is unbearably frustrating.

What almost redeems “See You in the Morning” are the performances. Bridges is completely at home in the central role, seeming relaxed around the children and convincingly decent in his relationships with the women. Krige is a good choice for his second wife; she has a way of conveying absolute good faith, and so it is painful to see her confronted with the dialogue in the big confession scene, where at a crucial turning point everything she is given to say sounds false.

The movie was written and directed by Alan J. Pakula, and is, like Blake Edward’s “That’s Life,” one of those unsparing movies of experience and analysis in which the audience is not spared. The screenplay is so scrupulous, so fair, so enlightened and so intelligent that real people have trouble shouldering it aside so that they can share messy human emotions. Nothing is ever quite this neat. (And the film’s level of taste is so high that a closing scene, involving a couple of cops, seems even more contrived and idiotic than it is.) I liked the people in “See You in the Morning.” I just wish they felt free to like themselves more. Actually, I don’t really know if that’s true. It’s just that after listening to them for almost two hours, I find myself thinking in phrases like that. Phrases about liking themselves more. Maybe I’m only saying that. Possibly I have a resentment against them. It’s hard to be sure. I’ll see you in the morning.