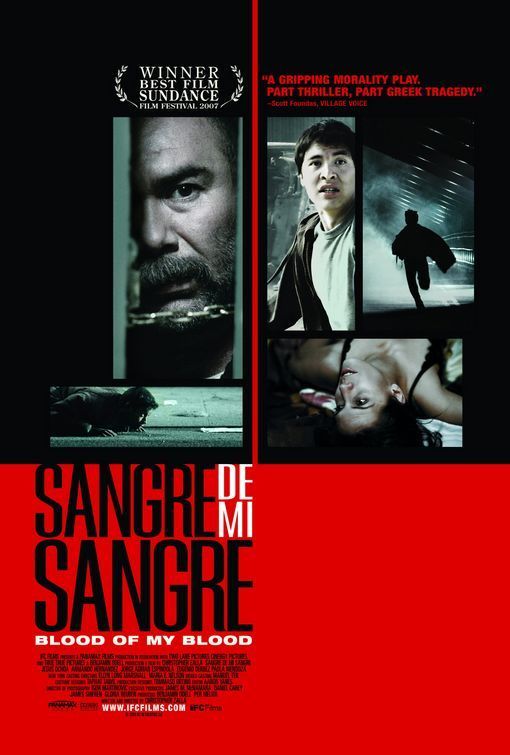

“Sangre de Mi Sangre,” the grand jury prize winner at Sundance 2007, gives us wonderful actors struggling in a tangled web of writing. The film is built around two relationships, both touching, both emotionally true.

But time after time, we’re brought up short by absolute impossibilities and gaping improbabilities in the story. To give one example: A newly arrived Mexican immigrant struggles to find his father in New York City. All he has is the 17-year-old information that the man works in (or perhaps owns) a French restaurant. Working his way through the Yellow Pages listings of French restaurants, he successfully finds his father. Uh-huh.

Let’s back up to earlier screenplay questions. We meet the hero, Pedro, as he escapes from Mexico by quickly scaling a fence along the U.S. border. Is it that easy to cross? Never mind. Waiting on the other side (not miles away, or hidden) is a truck for taking immigrants to New York. Wouldn’t U.S. Border Patrol agents notice it, in full view in an urban area? Pedro is hustled inside, the doors are slammed, and the truck begins a 2,500-mile journey that can apparently be survived on half a taco and a small bottle of water. More surprising still is that no effort is made to charge Pedro for the trip. He rides for free.

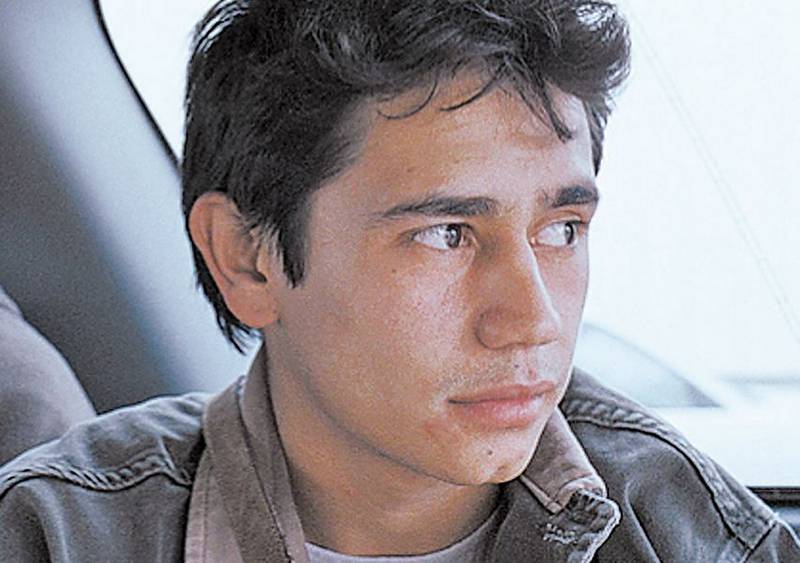

Pedro (Jorge Adrian Espindola) is young, earnest, trusting. On the journey he makes a friend of Juan (Armando Hernandez) and tells him his story: He hopes to find his father in New York and carries a letter to the old man from his mother. When Pedro wakes up at the end of the trip, Juan has already disappeared with the letter.

Juan is enterprising and decides to pose as Pedro; maybe it’s true, as Pedro’s mother claimed, that the father owned the restaurant where he earned money, which he sent home for several years. But why a French restaurant? Using the address on the envelope, Juan easily finds the shabby apartment of old Diego (Jesus Ochoa), who has never seen him and has no desire to acquire a son. But Juan is ingratiating and tells a convincing story; after all, he has read the letter, and Diego refuses to.

Meanwhile, the “real” Pedro wanders the streets, remembering only his father’s street address (still accurate after 17 years). He enlists Magda, a hard-worn Mexican girl, who does drugs, makes a living by her wits and her body, and wants nothing to do with Pedro. They nevertheless become confederates, picking up $50 here or there by performing sex for men who want to watch.

At this point you’re rolling your eyes and wondering how the grand jury at Sundance, or any jury, could have awarded such a story its prize. But you would have missed what makes the film special: the relationships. Juan does such a good job of playing Pedro that he convinces Diego he really is his son. And the real Pedro gets a quick series of lessons in surviving the mean streets, and comes to care about (not for) Magda.

The truest of these relationships, paradoxically, is the false one. Jesus Ochoa, a much-honored Mexican actor, creates a heartbreaking performance as Diego, the “old man,” as Juan always calls him. He was once in love in Mexico, left, sent money home, returned, and then (after apparently fathering the real Pedro), returned to New York 17 years ago. Maybe he told his wife he owned a restaurant, or maybe she lied about that to her son. No matter. He is a dishwasher and vegetable slicer, who earns extra money by sewing artificial roses. He has money stashed away. He is big, burly, very lonely. He comes to care for this “son.” Despite Juan’s deception, Juan comes to care for him — almost, you could say, as a father.

Magda is a tougher case. She does not bestow her affection lightly, nor is the real Pedro attracted to prostitution as a way for them to earn money. But Christopher Zalla, the director, does a perceptive, concise job of showing us how Magda lives on the streets and nearly dies. Magda and Pedro are together as a matter of mutual survival.

Pedro, Juan and Diego have paths that must eventually cross, we think. See for yourself if they do. And try not to ask why the police, planning to break down a door by surprise, would announce their approach with five minutes of sirens. The story’s conclusion is rushed and arbitrary, but so perhaps it has to be. “Sangre de Mi Sangre” (“Blood of My Blood”) is a film that stumbles through a maddening screenplay but nevertheless generates true emotional energy.