On May 30th, 2020, most Earthlings’ minds were not focused on a billionaire-funded rocket soaring into the sky, but on the abhorrent image of a Black man’s neck getting ground into the street. The historic first manned launch of the SpaceX spacecraft, Dragon 2, to the International Space Station was almost entirely overshadowed by the murder of George Floyd by white police officers in Minneapolis just five days prior. The racial reckoning triggered by this atrocity, combined with the global pandemic, rendered the expensive phallus-shaped rocket as mere fodder for late night jokes, epitomized by the guest hosting of its chief designer, entrepreneur Elon Musk, on “Saturday Night Live” last year. Questlove’s exhilarating Oscar-winning documentary, “Summer of Soul (…or, When the Revolution Could Not be Televised),” showed how the attendees at the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival—the Black equivalent of Woodstock that deserves to be just as infamous—asked why they should care about a man landing on the moon when there are so many problems in need of money and awareness on the ground. It’s an excellent question, especially in light of how white privilege has been woven into the fabric of the space race.

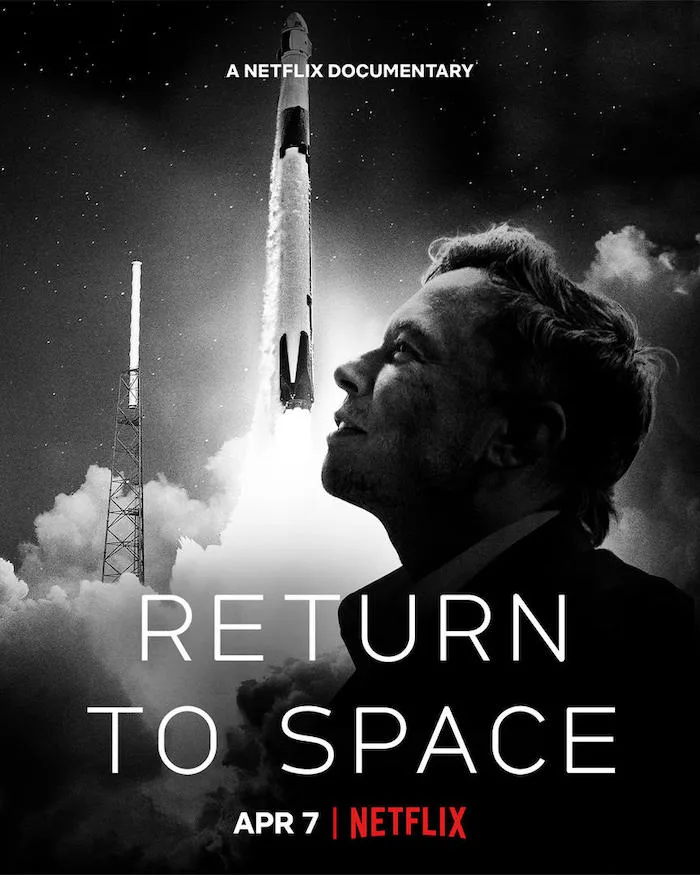

Yet “Return to Space,” the latest optimistic portrait of real-life individuals achieving the seemingly impossible from Oscar-winners Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi (“Free Solo”), invites us to give SpaceX another look, arguing that it is indeed worthy of our attention. The film’s overtly uplifting tone would cause it to have no qualms from SpaceX’s publicity team, though it does briefly touch upon the reasons why Musk and his rival, Amazon’s Executive Chairman Jeff Bezos, have been mocked, namely their obscene wealth and off-putting egos. Musk’s answers about aiming to make mankind a multi-planetary civilization, starting with the colonization of Mars, sound like they have been rehearsed from his press notes, yet what’s most disarming about Musk in Chin and Vasarhelyi’s film is how openly emotional he proves to be. Tears form in his eyes when he becomes the target of damning skepticism from his hero Neil Armstrong, and he gets choked up when answering a question about how he grapples with the risks faced by astronauts and beloved fathers Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken, being a parent himself. And it was during his appearance on “SNL” in which Musk publicly acknowledged that he has Asperger’s Syndrome, a revelation that contextualizes much of what we see here, as well as further humanizing the man behind the headlines.

Ultimately, it is the bravery and integrity of Hurley and Behnken that earns our investment in the success of Dragon 2, prompting us to hold our breath as each unprecedented step forward is made with the full knowledge that failure could occur at any second. The fact that the film’s 128-minute running time breezes by is a testament to the expert editing of Daniel Koehler, Dan Duran and Phillip Schopper, who intensify each risk taken by Musk’s team by recalling the previous disasters that haunt them, such as the disastrous reentry into Earth’s atmosphere of the Space Shuttle Columbia in 2003. I found myself on the edge of my seat all the way up to the very end of their 62-day mission, when it takes a few too many agonizing beats for their parachutes to inflate. This is yet another Netflix release sorely deserving of the big screen treatment, with its typically awe-inspiring views of Earth from above, motivating the astronauts to voice familiar epiphanies about how small we are in the universe and how the divisions between countries cannot be glimpsed from space. Especially touching is the astronauts’ care for their children, and by extension the future of our species, who they believe will be able to reach for the stars in ways no previous generation has.

Apart from its amusing shape, the Dragon 2 is distinguished by its reusability, making it cost far less tax dollars than previous space vehicles. One of the film’s most thrilling sequences shows how the rocket is able to remain standing while successfully hitting its mark upon landing just as the ships did in “2001: A Space Odyssey,” a film clearly referenced by Strauss’ “Blue Danube” waltz on the soundtrack. Among the film’s persuasive array of talking heads is SpaceX president Gwynne Shotwell, who believes that someone like Musk was needed to break through the bureaucracy of the space program, and that his vision more than makes up for his eccentricity. His lack of interest in pretending to be a model citizen in the eyes of NASA, as witnessed when he smokes marijuana on camera during Joe Rogan’s podcast, is reflected in the film’s causal inclusion of f-bombs, the sole barrier to making this picture acceptable for classroom viewing. So intent is the film on reigniting the audience’s excitement about space exploration that it fails to tackle questions about the elitism of figures like Musk and Bezos, whose profit-driven goals threaten to reduce what should be innovation for all to a competition for showing off whose “rocket” is bigger.

As feel-good entertainment, “Return to Space” is thoroughly engaging, containing some of the same warmhearted appeal as classics like “The Right Stuff” and “Apollo 13.” It is stunning to behold what SpaceX has been able to accomplish working outside of the system, as many visionaries do, creating technology to move us beyond Earth, which Musk dubs the “cradle of humanity,” nearly a half-century after our last moon landing. Whether this venture deserves the majority of our attention amidst the monstrous invasion of Ukraine, climate catastrophes, rising authoritarianism, institutional racism and the ongoing pandemic is another matter entirely. With so much presently at stake on our planet, we should be doing far more than merely planning an escape reserved for Musk and Bezos’ multi-billionaire club. Perhaps mankind should be less interested in becoming a multi-planetary species before they secure the future of life on their first and, as of now, only home. All that being said, Chin and Vasarhelyi make a solid case for why space exploration should continue, and the benefits we could reap from it, provided it doesn’t keep our heads perpetually lost in the clouds.

Now playing on Netflix.