There’s no room for the concept of workman’s compensation in the world of the Hong Kong stuntman. Although certain stunts involve an 80 percent chance of a trip to the hospital, that’s all in a day’s work, and the stuntman who complains risks losing face with his employers — and his fellow stuntmen.

So we learn in “Red Trousers: The Life of the Hong Kong Stuntmen,” a rambling and frustrating documentary that nevertheless contains a lot of information about the men and women who make the Hong Kong action film possible. Not for them the air bags and safety precautions of Hollywood stuntmen. Quite often, we’re stunned to learn, their stunts are done exactly as they seem: A fall from a third-floor window, for example, involves a stuntman falling from a third-floor window.

There is a sequence in the film where a stuntman is asked to fall off a railing, slide down a slanting surface to a roof and bounce off the roof to the floor below. It is rehearsed with pads on the floor. When the shot is ready, the director tells his stuntman, “No pads. Concrete floor.” And when the stuntman lands on the concrete incorrectly the first time, he insists on doing the stunt again: “I came off the roof at the wrong angle. This time, I will get it right.”

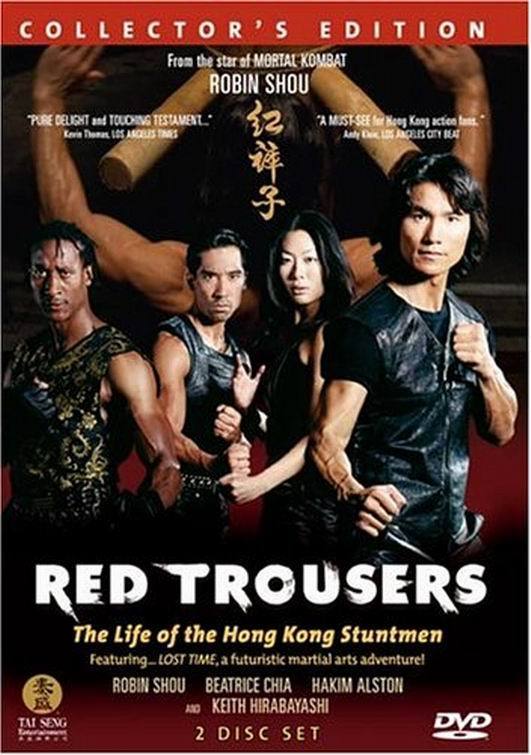

Are stuntmen ever killed? No doubt they are, but you will not hear about it in this doc, directed by the onetime stuntman and current actor and director Robin Shou (“Mortal Kombat”). We do learn of a stuntman who was gravely injured when his wire snapped and he fell from a great height to land on jagged rocks. We see the shot as the wire snaps, and then the cameras keep rolling, Jackie Chan-style, as the crew races over to the man, who is screaming in pain. There’s a call for pads to put him on, and then he’s carried off on the shoulders of five or six crew members. We realize with astonishment that there is no medical team standing by, no ambulance, no provision at all should the stunt go wrong.

Later, visiting the injured stuntman in his village, we learn that he needed many operations over a period of two years on a shattered leg, but thank goodness his facial cuts didn’t leave scars. He was paid $25 a day for two days of work, he observes. What about compensation? No mention. Good thing they have socialized medicine.

Wires are, of course, often used in stunts to make the characters appear to defy gravity, but it would be wrong to assume they make stunts any easier. We see stunts where the wires are used to slam a stuntman against a wall or spin him into a fall. The wires do not break the impact or slow the fall.

We hear a lot about how carefully Hollywood stuntmen prepare their “gags,” but consider a scene in this movie where a stuntman jumps off a highway overpass, lands on top of a moving truck and then rolls off the truck onto the top of a van before falling to the highway.

How was the stunt done? Just as it looks. “My call was for 5:30 and the stunt was finished by 5:45,” the stuntman reports cheerfully. Good thing the truck and the van were in the right places, or he might have been run over, or have fallen from the overpass to the pavement.

There are a lot of interviews with stuntmen in the movie, who repeat over and over how they love their work, how excited they are to be in the movies, how of course they’re frightened but it’s a matter of pride to do a stunt once you have agreed to it — if word gets around that they’ve balked, the jobs might dry up. They take pride in the fact that Hong Kong stuntmen are allowed to make physical contact with the stars, while in Hollywood, the stars must never be touched.

All of this has a fascination, and yet “Red Trousers” is a jumbled and unsatisfying documentary. It jumps from one subject to another, it provides little historical context, it shows a lot of stunts being prepared and executed but refuses to ask the obvious questions in our minds: Are there no laws to protect injured stuntmen? Are they forced to sign releases? How many are killed or crippled? Why not use more safety measures?

Instead, Shou devotes way too much screen time to scenes from “Lost Time” (2001), a short action film he directed. Yes, we see stunts in preparation and then see them used in the movie, but sometimes he just lets the movie run, as if we want to see it.

He explains that the term “red trousers” originated with the uniforms of students at the Beijing Opera School, which produced many of the early stuntmen, and shows us students of the opera school today; they begin as children, their lives controlled from morning to night, just as depicted in Chen Kaige’s great film “Farewell My Concubine” (1993). Shou interviews some of the students, who are still children, and as they affirm their ambitions and vow their dedication, we glimpse a little of where the stuntman code comes from. But if the wire breaks some day, they may, during the fall, find themselves asking basic questions about their profession.