“The world is too much with us late and soon.” This was true when William Wordsworth wrote it in the early 1800s, and it’s even more true now. There is too much of “the world” to absorb. Opting out is increasingly impossible. Some gas stations have little television screens above the pumps, blasting CNN at you, because apparently the 45 seconds it takes to pump your gas is way too long for any human to be unplugged from the news dump. You sit in waiting rooms, at airport gates, and the television is on, and it’s always news, the nonstop flow of information, propaganda, noise. Is the human brain built to absorb so much of “the world”? How do we filter anything? Matt Wolf’s new documentary, “Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project,” is an interesting meditation on these ideas, as well as a character study of a fascinating news-junkie with a mission.

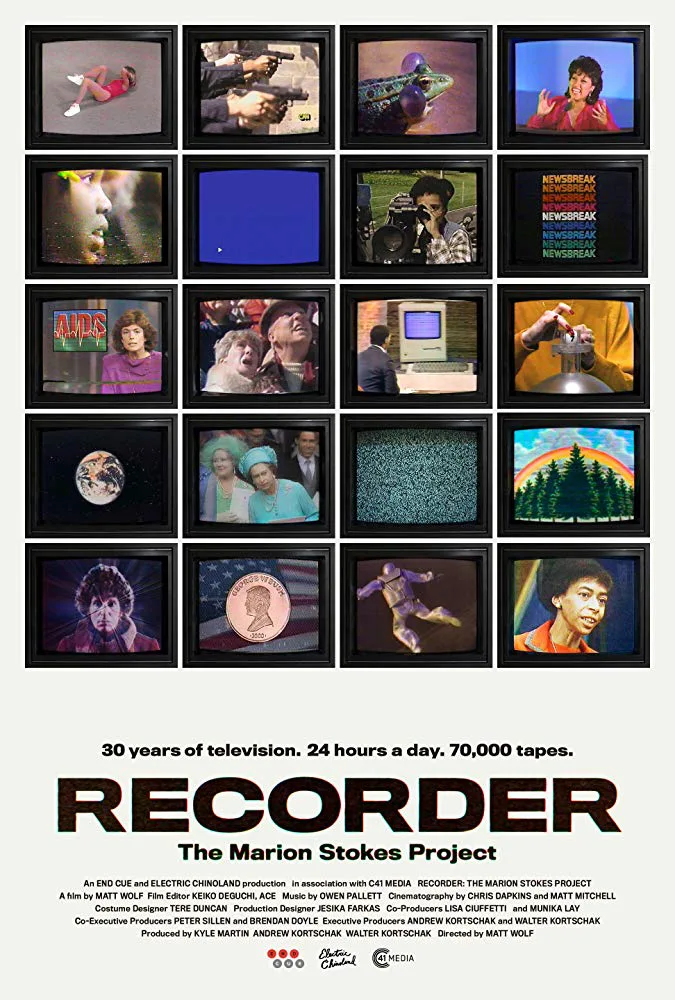

When Stokes, who started out as a librarian, died in 2012, she left behind a massive archive of video tapes (70,000 in total) of all of the television shows she had recorded over a 35-year period. To create such an archive, she spent all day every day watching television, multiple screens going at any given time, popping tapes in and out. She couldn’t keep up with labeling, so she’d stick a Post-It note on each tape, detailing what was on it. Keeping up with the archive of news was a driving obsession, a compulsion, and she was aided in this by new technology like the VCR.

“Recorder” is a compelling look at one very specific eccentric woman, who lived in the era when news went from local to national, from one time-slot to all day long, and who sensed in this shift something alarming, something new, and who responded by trying to capture all of it, catalog and save. Who was Marion Stokes? She was heavily involved in left-wing politics with her first husband, so much so that she was being groomed for a leadership position in the Communist Party, and she also wanted to emigrate to Cuba. After the marriage fell apart, she became a co-host of “Input,” a Sunday morning talk show on a CBS affiliate in Philadelphia. Her co-host was John Stokes, a wealthy local man: the two of them wanted to create a space where people with different viewpoints could discuss the hot topics of the day. Marion and John fell in love, and got married. (The footage from “Input” shows their chemistry, a chemistry of listening and care with one another’s viewpoints.) Their connection was so intense it shut everyone else out, including their children. Eventually, Marion and John lived as hermits, for decades, devoted to maintaining her ongoing video-taping project, to the exclusion of all else.

Wolf’s approach with this beguiling material is to utilize much of Stokes’ archive, which ends up being an historical survey of the latter half of the 20th century into the first years of the 21st. The Iranian hostage crisis in 1979 started it all. Stokes became aware of how the news was being shaped and molded, with wall-to-wall coverage of the crisis (Mark Bowden describes the media phenomenon in his book about the hostage crisis, Guests of the Ayatollah). She started recording news programs, like the brand-new “Nightline,” and when CNN launched in 1980, her project expanded overnight.

The montage from her tapes, culled from a daunting archive, is a record of an entire era, from news of worldwide importance, like the hostages in Iran, to the story of “Jessica McClure,” the baby trapped in a well who captivated American audiences for days on end. There’s footage of the Elian Gonzalez case, the Challenger explosion, or local news stories like a woman who chose to be buried with her Cadillac. Stokes did not select: she recorded it all. She noticed how small local stories were now blown up to national stories, mainly to keep the 24/7 news business going. Her final tape before she died was of the Sandy Hook massacre.

“Recorder” works on multiple levels. The Marion and John’s apartment—lined with video tapes—looks like an episode of “Hoarders.” Hoarding comes out of anxiety and a desire to control. Any collector understands this. The issue of “hoarding” and “collecting” has deeper elements, though, and it is in this realm that “Recorder” really resonates, especially when it addresses the importance of preservation and archiving. The fantasy is that with the internet, everything can be saved and found, everything is available. This is so far from the truth it’s outrageous that people still seem to believe it. We see the fantasy that “streaming” platforms are going to be this great thing, and of course they are, but the fantasy that everything will be available is just that: a fantasy. With every advance of technology—from VHS to DVD to Blu-ray to streaming—movies have been “lost” in the process, not making the transfer. I will continue to buy physical media, since I do not trust the “landlords.”

In terms of news programming, what has happened is that if it’s not on the internet, it might as well not exist at all. And so history, context, nuance, even the ability to analyze and compare and contrast, is lost. Local news stations don’t have the capability to save every single segment, and in so many cases, Stokes’ tapes may be the only copy. Some of these programs have never been seen since their first airing.

She kept up this pace for 35 years. Her relationships suffered. She stopped being able to go out. Why did she do this? Was she just an obsessive? Who was this gigantic archive even for? One of her assistants, interviewed in “Recorder,” says he believed she did it “for the betterment of mankind.” Exaggeration? I’m not so sure. Knowledge really is power and Stokes understood that. But let’s not forget the most important detail: Stokes may have stopped working as a librarian early on, but once a librarian, always a librarian. This is what librarians do. They want people to be able to find information, they try to clear the way so people can find what they need. As the daughter of a librarian, the daughter, too, of a collector, I understood Stokes’ drive to save, collate, organize, keep. My father passed down his obsessions to me. Stokes’ work is an urgent reminder of the importance of archives, the importance of preserving those archives so that they can be made available, open to all.