Watching other people piece together jigsaw puzzles would not sound like the most inherently cinematic pursuit, nor would it seem to provide much opportunity for character development. Puzzles are a solitary activity—a chance to focus quietly and inwardly, to retreat from the peripheral noise of the outside world.

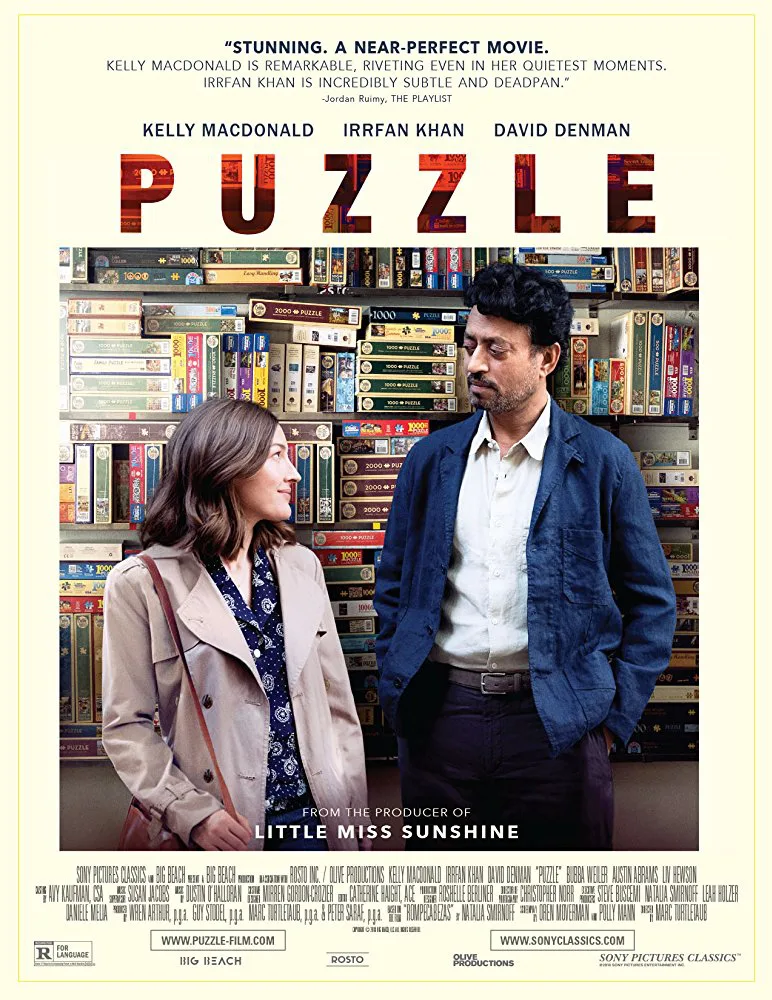

All of which makes “Puzzle” such a lovely surprise. A million tiny revelations make up one massive arc, and Kelly Macdonald positively radiates hope and joy throughout that process. The directorial debut from producer Marc Turtletaub (“Little Miss Sunshine,” “Loving”) gives Macdonald a rare and welcome starring role in which to shine—albeit in an understated and unassuming way, at first. Watching her blossom throughout the course of the film in such an unexpected way is a true pleasure. And while “Puzzle” adheres to a bit of a formula in depicting her character’s path of self-discovery, it’s filled with vivid details and lovely grace notes along the way.

A remake of 2009’s “Rompecabezas” from Argentinean writer/director Natalia Smirnoff, “Puzzle” is an intimate look at Macdonald’s character, Agnes, whose entire existence has consisted of caring for others. Whether it was her late immigrant father, her mechanic husband, Louie (David Denman), their two grown sons (Bubba Weiler and Austin Abrams) or her close group of church friends, other people’s needs have always come before Agnes’ own. She’s actually reached her 40s without even knowing what her needs are.

Working from a script by Oren Moverman and Polly Mann, Turtletaub reveals this dynamic in a sly and deliberate way at the film’s start. We see Agnes putting up balloons and decorations in her middle-class home, then serving snacks and cleaning up messes once her party guests have arrived. When it comes time to bring out the birthday cake, Agnes is the one to light the candles—and she’s also the one who blows them out. Turns out this party is for her, but she’s stuck doing all the work, just as she would be on any ordinary day.

But one of the gifts she receives is a jigsaw puzzle, which she spontaneously sits down and quickly completes at the dining room table one afternoon. It has 1,000 pieces, and she breezes through it with ease before breaking it all apart and starting all over again. This awkward, introverted woman suddenly reveals herself to be a virtuoso who’s totally in command. Turtletaub invites us into the quiet of these private moments, shooting them in unadorned fashion, making us feel as if we’ve entered a sacred place by sitting at the table beside her.

The fact that Agnes displays a knack for such an old-fashioned, analog activity makes sense, even though she never knew she had it in her. She dresses in conservative cardigans and skirts and pins her hair back simply, disorienting us at first as to the era in which “Puzzle” takes place. Another birthday gift she receives is an iPhone, which she’s initially reluctant to use: “It’s like carrying a little robot in your purse,” she complains. But the puzzle and the phone together become the tools she ultimately uses to explore the world outside her insular cocoon of blue-collar Bridgeport, Connecticut.

Agnes eventually works up the nerve to hop on a train to New York City, where she discovers an entire store full of complicated puzzles for her to explore, as well as an unlikely friendship with a champion puzzler named Robert who seeks a partner for an upcoming competition. He’s played by the great Irrfan Khan, who immediately changes the tone and energy of “Puzzle” simply through his charismatic presence. A wealthy inventor living alone in an ornate Manhattan brownstone, Robert has a playful, low-key sense of humor, which he uses to draw Agnes out of her shell. Macdonald and Khan have an enjoyably prickly chemistry with each other off the top, which steadily evolves into a bond that’s unexpectedly deeper.

At the same time, though, what’s fascinating about “Puzzle” is the way in which it depicts the other characters in Agnes’ life. They may look like types, but they’re more complicated than that. Even though she keeps her day trips and puzzling a secret from her family—and she’s a surprisingly cool liar—she does so through her own sense of insecurity. There’s no real “villain” here, per se. Her husband, Louie, is a decent, hardworking man who happens to have traditional notions of family and gender roles. He’s grown accustomed to having dinner waiting for him on the table when he comes home from a long day’s work, because that’s the way it’s always been. He’s never cruel or abusive toward her. He loves her—but he also expects her to go to the grocery store to pick up the specific kind of cheese he likes.

Meanwhile, Agnes’ sons are struggling to assert their own senses of identity and purpose as they grow up and prepare to leave the nest (something her older son, Ziggy, probably should have done a while ago). So as Agnes’ confidence grows, and she shows flashes of anger or frustration at the restrictions of her daily life, her sons instinctively sympathize with her. They’re all just looking for a piece of something that feels real and true—a missing piece that will complete them.

“Puzzle” wisely doesn’t complete the whole picture in easy or obvious ways, but rather gives us the space to consider the solutions for ourselves.