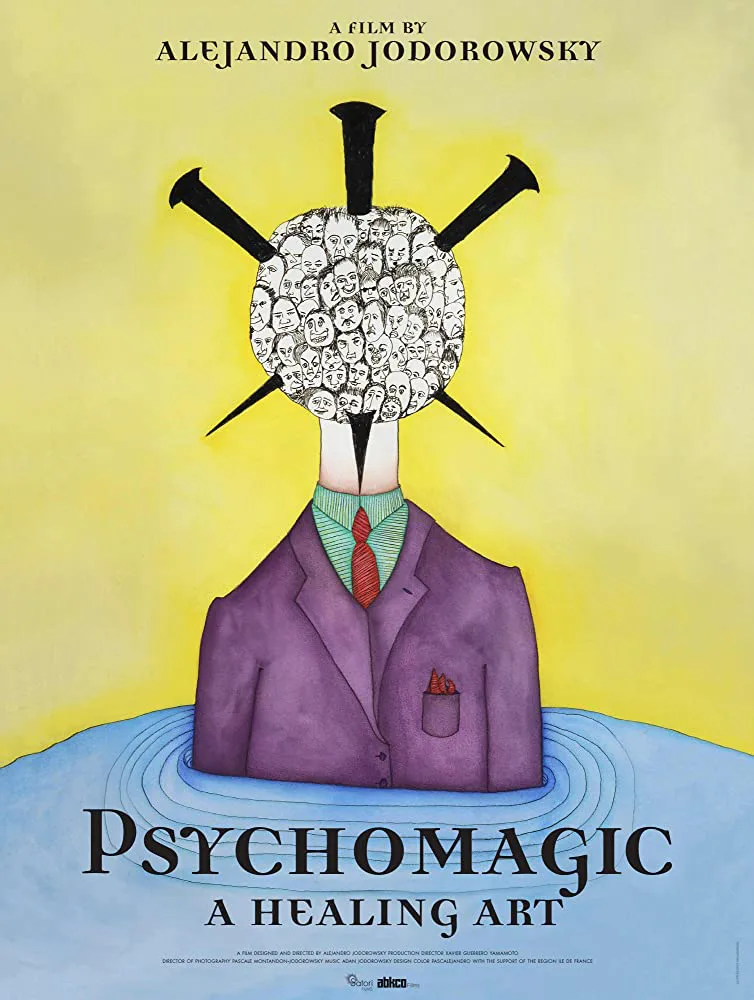

“Psychomagic, A Healing Art,” a new documentary about and by Chilean shaman-cum-filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky, is many things, including an advertisement of Jodorowsky’s surreal holistic medicine practice, which sometimes involves public exhibitionism, bizarre costume changes, and interpretive full-body massages. Jodorowsky’s latest film is also a portrait of the artist as an older, and more palatable father figure (he refers to himself as a “fatherly archetype” in one scene).

It is, in that sense, similar to Jodorowsky’s last two movies, the autobiographical scripted dramas “The Dance of Reality” and “Endless Poetry”: all three films represent the 91-year-old artist’s desire to control how we see his still-mystifying art, and its purportedly therapeutic value. So viewers should not expect “Psychomagic” to explain anything about Jodorowsky’s work he doesn’t want to address. Thankfully, Jodo’s latest is also way too weird to be hagiographic. It’s indulgent, absurd, frustrating, and more than a little gross. It’s also idiosyncratic and funny enough, and in ways that Jodo’s fans will probably love.

As usual, Jodorowsky first provokes his audience, and then explains himself in ways that make his sensationalistic methodology both more and less sensible. We see footage of “initiatory massages,” a hands-on and highly unorthodox style of therapy that Jodo invented for the sake of forcing his would-be patients into a personal breakthrough.

Some of Jodo’s patients literally muscle their way through their issues—with parents, spouses, and/or their own bodies—by being massaged, buried alive, or otherwise exorcised in public. A group of women paint self-portraits with their own menstrual blood. A 40-something grapples with his daddy issues by donning a Captain Hook-style pirate outfit, complete with puffy shirt and plumed tricorner hat, and playing an emotional ballad in the middle of an empty theater. A self-described “couple in crisis” attach chains to their ankles, and trudge around Paris without once looking at each other. Your guess is as good as mine since “Psychomagic” only provides so much information about these people and their problems.

That said: “Psychomagic” makes sense, if only as a heavily-redacted Rosetta Stone for Jodorowsky’s art, which includes films, comics, “Panic Movement” theatrical performances, novels, and more. Jodorowsky explains himself throughout, using clips from his older movies (including “Tusk”!) and a few on-camera interviews: “One can’t teach the unconscious to speak the language of reality. Reason needs to be taught to speak the language of dreams.” Jodo also uses interview footage with grateful patients to illustrate the healing powers of auto-suggestion, I mean psychomagic. An unidentified throat cancer victim testifies after Jodorowsky leads a circus-tent-full of on-lookers in sending her good vibes: “Healing comes from the center.” That line may be the only point of contact between Jodorowsky’s art and popular self-help books like The Secret.

Another patient, who wants to stop stuttering, raises more questions than he answers when he puts on a Donald Duck sailor suit, and agrees to have his junk grabbed by Jodorowsky. “I will pass manly energy along to you,” Jodorowsky says. The look of relief on this guy’s face then suggests that he agrees with Jodo, and his counterphobic approach to therapy. But it’s hard to nod along in agreement given that, as some readers may recall, Jodorowsky advertised his 1970 acid western “El Topo” by saying, in interviews, that he “really raped” co-star Mara Lorenzio. I tend to agree with film critic (and friend) April Wolfe when she writes: “You might take his claim with a grain of salt as another of Jodorowsky’s hype experiments. Still, that a director would brag about raping his co-star to publicize a film is mind-boggling. That critics don’t seem to care is worse.”

In this harsh light, “Psychomagic” seems like an inadequate, and relatively PR-friendly self-defense, despite its many deliberately confrontational elements. It’s a movie that boils down to dubious self-mythologizing one-liners like “nothing that is human is ridiculous.” At the same time, “Psychomagic” is often immediately engaging and amusing. I mean, where else are you going to see a self-described healer bury someone up to their necks, and then, after covering their patient’s face with an overturned bowl, sic a wake of vultures on them? The vultures do what they do, devouring a pile of glistening offal, and the patient walks away from his premature burial with a smile on his face. But only after he releases a photo of his father, attached to a red balloon, into the stratosphere. It’s ridiculous, it’s unbelievable, it’s bullshit—it’s Jodo!

Now available exclusively at Alamo on Demand.