It is hard to imagine your parents as young people, when you are older than they were when they reared you. We understand other adults, but it is so hard to see parents clearly; we still regard them through the screens of childhood mystery. In his old age, the thoughts of the Swedish director Ingmar Bergman have turned toward his childhood, and particularly toward the secrets of his parents’ marriage.

His father was a Lutheran minister. His films paint his mother as a high-spirited woman who often found her husband distant or tiresome. Both his parents were steeped in religion and theology, which did not prevent them from doing wrong, but equipped them to agonize over it. In four films, one as a director and three where others directed his screenplays, Bergman has returned to the years when he was a child and his parents were in turmoil. “Fanny and Alexander” (1983) was a memory of childhood. Bille August’s “The Best Intentions” (1992) was the story of the parents’ courtship.

“Sunday’s Children” (1994), directed by Bergman’s son Daniel, was about the boy’s uneasy relationship with his father. Now comes “Private Confessions,” the story of his mother’s moral struggles. He calls these films fictions because he imagines things he could not have seen, but there is no doubt they are true to his feelings about his parents. One would not live to 81 and tell these stories only to falsify them.

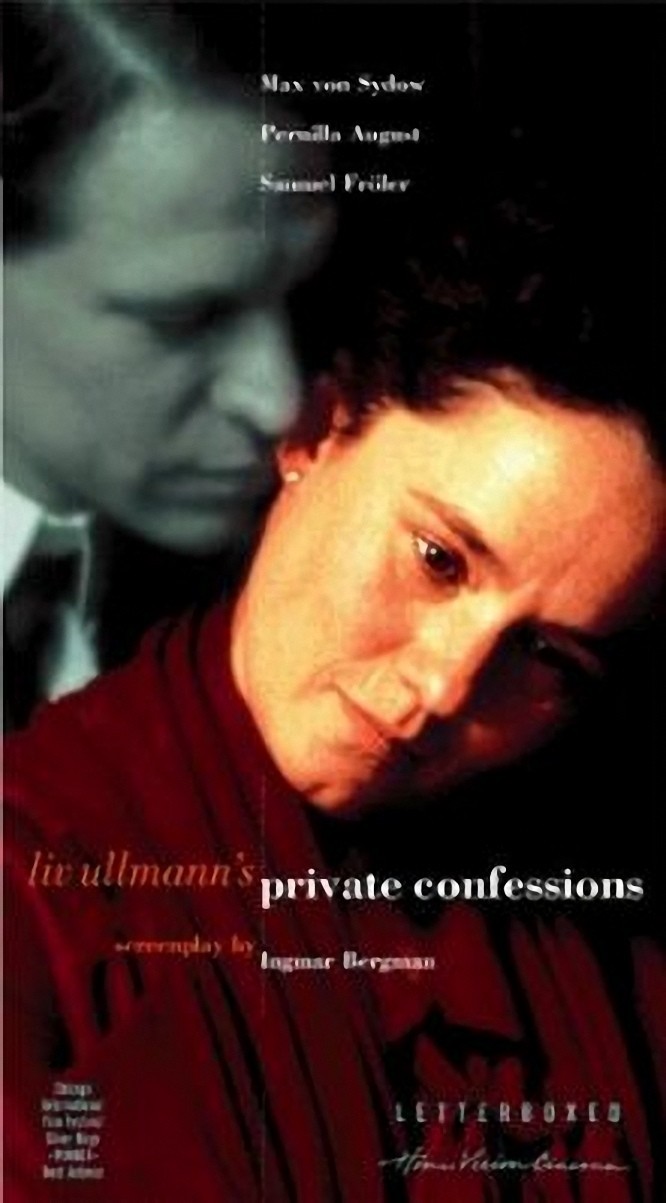

“Private Confessions,” based on Bergman’s 1966 book, has been directed by Liv Ullmann, an actress in many of his best films. The cinematographer is wise old Sven Nykvist, his collaborator for 30 years.

The actress playing Anna, his mother, is Pernilla August, who also played Anna in “The Best Intentions.” Uncle Jacob, Anna’s spiritual adviser, is Max von Sydow, the tall, spare presence in so many Bergman films from “The Seventh Seal” onward.

The film is divided into five “conversations.” An explanation is offered early, by Uncle Jacob. It is often wrongly thought, he tells Anna, that Luther abolished the Catholic sacrament of confession. Not exactly. He replaced it with “private conversations” in which sins and moral questions could be discussed with an adviser.

Jacob led young Anna through her confirmation, and they meet again as the film opens in the summer of 1925. She confesses to him that she has been an unfaithful wife. She has cheated on her husband, Henrik, with a younger man, Tomas. Both men are theologians.

Jacob tells her she must break off the relationship and tell everything to her husband. In the second conversation, set a few weeks later, she follows his advice, and we see that Henrik (Samuel Froler) is a cold man who views adultery less as a matter of passion than as a breach of contract. No wonder, he shouts, that the house contains “chipped glasses, stained cloths, dead plants.” The third conversation takes place before the other two, and involves a rendezvous between Anna and Tomas, which she has arranged in the home of a friend. Here we get insights into the nature of their relationship, and there is the possibility that for a lover Anna may have selected the man similar to her husband. He feels “gray and inadequate,” Tomas tells her the morning after, and keeps repeating, “One must be true.” Is it Anna’s fate to forever dash her passion against the stony shores of men who think before they feel? The fourth conversation, which contains the heart of the film, takes place 10 years later, when Jacob is dying, and wants to know the truth about what happened–about whether Anna followed his advice. She lies to him to spare his feelings.

They take communion together, and that sets up the fifth conversation, which takes place before all the others, the day before young Anna’s confirmation. In it she confesses to Jacob that she does not feel ready to take communion the next day. One must, of course, be in a state of grace and readiness to take the sacrament, and she does not feel she is. His advice to her at this time is the best he ever gives her.

The film is not about sex or adultery. It is about loneliness, and the attempt to defeat it while living within rigid moral guidelines. To understand it completely, we have to remember “The Best Intentions,” which tells the story of Anna and Henrik’s courtship, and shows her as warm and generous, he as already crippled by a cold childhood and an inferiority complex. There is just the hint–the barest hint, a whisper only–that the one man in Anna’s life who might have given her what she craved was Uncle Jacob.

A film like “Private Confessions” makes most films about romance look like films about plumbing. It is about Bergman’s eternal theme, which is that we are all locked in our own boxes of time and space, and most of us never escape them. They have windows but not doors. Anna’s problem is not morality but consciousness. To know herself is to accept that no one else will ever truly know her. Her final lie to Jacob accepts this truth, but at least as he dies she can make his own cell a little more peaceful.