The night air is filled with sounds: birds, insects, cows, a barking dog. But people sit at night, eyes closed, listening for cars approaching. The sound of cars means “they’re” coming. It’s too dangerous to even name them or put a label on them. They are just “they.” There are sounds that belong in this isolated mountain village, and sounds that don’t. Of all of the things Tatiana Huezo captures in “Prayers for the Stolen,” her first narrative feature, the terror of the night is most unnerving.

Huezo brings her documentary background to this fictionalized tale of an all-too-real humanitarian crisis unfolding in Mexico, the ongoing war between the government and the cartels, the rampant human rights abuses, the drug business, the international sex trafficking business. In many cases the “police” are either helpless against the cartels or work in concert with them. Thousands and thousands of people have been “disappeared,” with women and girls making up a significant percentage. They are abducted from their homes, often in broad daylight, and sold into sex trafficking or murdered. Their dead bodies are used to terrorize others into compliance. Boys and men are not exempt, often forced into working for the cartels, or to “give up” the female members of their family.

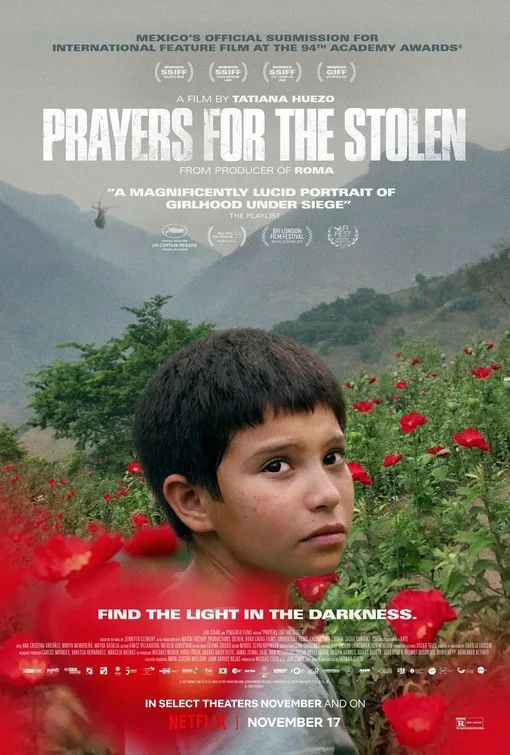

The Mexican-Salvadorean Huezo has created a film vibrating with dread, even more so since it is seen through the eyes of a child, Ana (Ana Cristina Ordóñez González, with a wonderfully expressive face), who perceives all that is happening. The adults, meanwhile, never speak of the events but plan grimly for the eventuality. The opening shot shows Ana’s mother Rita (Mayra Batalla), a careworn anxious woman, putting her daughter into a hole in the ground, a grave-sized indentation where Ana can hide if “they” come for her. Ana’s father is “over there”—America—and is supposed to send money home, but he never does. He never answers his phone. Like most adults in the town, Rita works in the nearby poppy fields. The children go to school, but it has become impossible to keep a teacher there; the situation is far too dangerous.

Despite this, Ana and her two best friends, Maria (Blanca Itzel Pérez) and Paula (Camila Gaal), resilient like children are, create their own little world. They’ve made up a game where they try to get totally in sync, all humming the same note, breathing at the same pace. They soothe one another. The adults around them are too frightened to do any soothing. The children strain to hear what the adults are saying, teachers leaving, other villages erecting barricades against the cartels. The girls are forced to cut their long hair very short because of “lice” says Rita, but, of course, it’s so they will look like boys, at least until adolescence arrives.

Ana is central, and it is through her eyes which we see this world, a world dominated by the tense silence of adults, and the sudden bursts of terror when the cartel “representatives” barrel into town, shooting guns in the air, whooping like conquerors. A family was taken in the night. Nobody knows where. Ana peeks through the windows of their home, dishes on the table, shoes by the bed. It is as though they were ripped up into the sky mid-meal.

The second half of the film, not as strong as the first half, takes place a couple of years later, with new actresses playing the trio: Marya Membreño (Ana), Giselle Barrera Sánchez (Maria), and Alejandra Camacho (Paula). The now tween-age girls still soothe one another with their in-sync game, and share a crush on their teacher. Their hair is still shorn close to their heads, and they look longingly at the little bottles of nail polish in the makeshift salon. Being a girl is a dangerous act. When Ana gets her period for the first time, Rita doesn’t hug her daughter. She looks terrified. They both know what it means. Huezo has done such an intuitive job of setting up the dangers that when the girls go swimming in the river, or walk home after school, chatting and laughing, you fear for them.

So much is left unsaid, and this adds to the intensity of “Prayers for the Stolen.” Cinematographer Dariela Ludlow immerses us into this world, its lush greenery and pitch-black shadows, the poisonous pesticide dropped on the village in a burning acidic fog, the quiet oasis of the school room. There’s a beautiful shot of a crowd of people standing on a hill at dusk, the only place in town where there’s cell service, their phones lit up as they try to contact loved ones, anyone on the “outside.” Much of the film depends on the young actresses, and they create a believable and very touching bond. Ana is tough and resilient, and her smile, when it comes, cracks her face open with joy. Any joy is short-lived. People are fleeing. The girls can no longer “pass” as boys. They are in grave danger.

Huezo’s approach is sensitive but powerful. The lack of explanatory dialogue keeps us fully immersed in the everyday reality of people who live in the terrifying crossfire, all of them vibrating with the silence of things that can’t be said, that don’t need to be said. Terror is the air they breathe.

In theaters and on Netflix today.