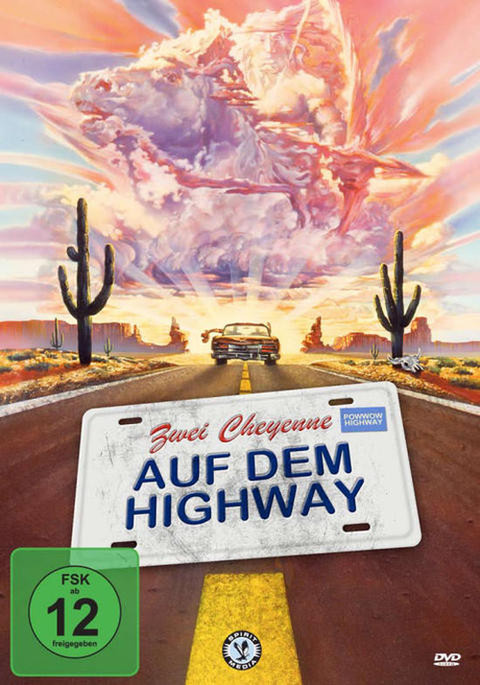

Anyone who can name his 1964 Buick “Protector” and talk to it like a pony has a philosophy we can learn from. Philbert Bono is the name of the philosopher. He is a member of the Northern Cheyenne tribe, and near the beginning of “Powwow Highway” he and a friend, Buddy Red Bow, set out to ride Protector from Lame Deer, Mont., to Sante Fe, N. M.

They go by way of the Dakotas, because to Bono the best way to get to a place is not always the straightest way.

“Powwow Highway” is the story of their journey, and in one sense it’s a road movie and a buddy movie, but in another sense it’s a meditation on the way American Indians can understand the land in terms of space, not of time. Philbert never states it in so many words, but it’s clear he doesn’t think of a trip to Santa Fe in terms of hours or miles, but in terms of the places he must visit between here and there to make it into a journey and not simply the physical relocation of his body.

The movie supplies a plot in order to explain why the two Indians need to take their journey, but the plot is the least interesting element of the film. It involves a scheme against Buddy, who is a tribal activist and opposes a phony land-rights grab that’s being directed at some Indian territories. His sister is thrown into jail in Santa Fe, and he must go there to bail her out, and that will get him out of Montana at a crucial time. And so on.

The plot is not the point. What “Powwow Highway” does best is to create two unforgettable characters and give them some time together.

It places them within a large network of their Indian friends so we get a sense of the way their community still shares and thrives. As Philbert points Protector east instead of south, as he visits friends and sacred Indian places along the road, he doesn’t try to justify what he’s doing. It comes from inside. And it comes, we sense, from a very old Indian way of looking at things. Buddy is much more modern and impatient – he’s Type A – but as their journey unfolds, he can begin to see the sense of it.

The movie develops a certain magical intensity during the journey, and much of that comes from the chemistry between the two lead actors.

Philbert is played by Gary Farmer, a tall, huge man with a long mane of black hair and a gentle disposition. He speaks softly and sees things with a blinding directness. Buddy (A Martinez) is more “modern,” more political, angrier. Their friendship has survived their differences.

The movie was shot entirely on location, and the set decoration, I suspect, consists of whatever the camera found in its way. (If this is not so, it is a great tribute to the filmmakers, who made it seem that way.) We visit trailer parks and dispossessed suburbs and pool halls and conve nience stores. We watch the dawn in more than one state, and we get the sense of the life on the road in a way that is both modern (highways, traffic signals) and timeless (the oneness of the land and the journey). And although I have made this all sound important and mystical, “Powwow Highway” is at heart a comedy, and even a bit of a thriller, although the way they spring Buddy’s sister from prison belongs to the comedy and not the thriller.

The movie is based on a novel by David Seals, which I have not read; the story resembles the tone in some of W. P. Kinsella’s stories about North American Indians. In Buddy it shows the somewhat fading anger of a man who once was a firebrand in the American Indian Movement (he has a concise, bitter speech about the programs “for” the Indians that will be an education for some viewers). In Philbert it finds a supplement to that anger in a man whose sheer, unshakable serenity is a political statement of its own.

One of the reasons we go to movies is to meet people we have not met before. It will be a long time before I forget Farmer, who disappears into the Philbert role so completely we almost think he is this simple, openhearted man – until we learn he’s an actor and teacher from near Toronto. It’s one of the most wholly convincing performances I’ve seen.

Most of the people who go to see “Powwow Highway” will already have seen “Rain Man,” the box-office best seller. Will they notice how similar the movies are in structure? Philbert does not have any sort of mental handicap, as the man with autism does in “Rain Man,” but he has a similar, absolutely direct simplicity. Both characters state facts.

They catalog the obvious. Deep beneath the simplicity of Philbert’s statements is a serene profundity (we cannot be quite sure what lies at the bottom of the autistic’s statements). In both movies the other man – younger, ambitious, impatient – learns from the older. Meanwhile, in both movies, the men become friends while they drive in ancient Buicks down the limitless highways of America.