The father prepares the postbag the night before, arranging the mail in the order it will be needed, and wrapping everything carefully against the possibility of bad weather. This will be the last time he packs the bag, and the first time the route will be carried by his son — who is inheriting his job.

The next morning unfolds awkwardly. The boy’s mother is worried: Will be find the way? Will he be safe? The father (Teng Rujun) is unhappy to end the job that has defined his life. But his son (Liu Ye) will be accompanied by the family dog, who has always walked along with the father and knows the path. It is a long route, 112 kilometers through a mountainous rural region of China, and the trip will take three days. The son shoulders the bag and sets off, and then there is a problem: The dog will not come along. It looks uncertainly at the father. It runs between them. It is not right that the son and the bag are leaving, and the father is staying behind.

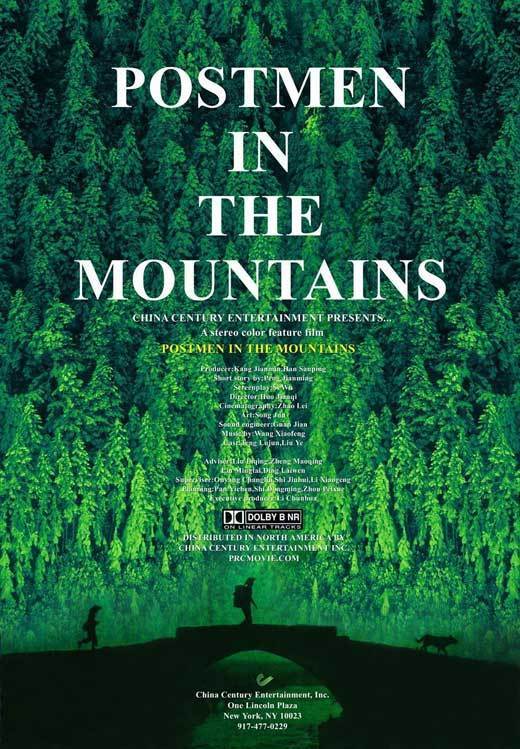

This is the excuse the father is looking for, to walk the route one last time and show his son the way. The two men and the dog set off together in Huo Jianqi’s “Postmen in the Mountains,” a film so simple and straightforward that its buried emotions catch us a little by surprise.

The trek represents the longest time father and son have ever spent together; the boy was raised by his mother while his father was away, first for long periods, then for three days at a time. They’ve never even had much of a talk. Now the son observes that his father, who seemed so distant, has many friendships and relationships along the way — that he plays an important role, as a conduit to the outside world, a bringer of good news and bad, a traveler in gossip, a counselor, adviser and friend.

The villages and isolated dwellings are located in a region that must have been chosen for its astonishing beauty. There are no factories, freeways or fast food to mar the view, and the architecture has the beauty that often results when poverty and necessity dictate the function, and centuries evolve the form. The dog seems proud to show these things to his new young master.

There are several vignettes, as the postman brings personal news between villages, and in one case continues a long-running deception he has practiced on a blind woman. Her son in the city sends money, but does not write; the postman invents a letter to go with every delivery, “reading” to her out of his imagination. Now that will become part of the son’s job.

They receive food and shelter along the way. One night they build a campfire under the stars. They don’t share deep philosophical truths, but simple facts about the job, which gradually become the father’s explanation to his son about the life he has led, about his satisfactions and regrets. It is too bad he was never at home very much — but now his son will find out for himself that carrying the mail is an important job and must be taken seriously.

And that’s about it. The movie consists of the journey, the conversations, the scenery, the little human stories. No big drama. No emergencies. Just carrying the mail, which over the years has supplied the threads to bind together all of these lives. When the son sets out along on his next journey, the dog cheerfully goes along.