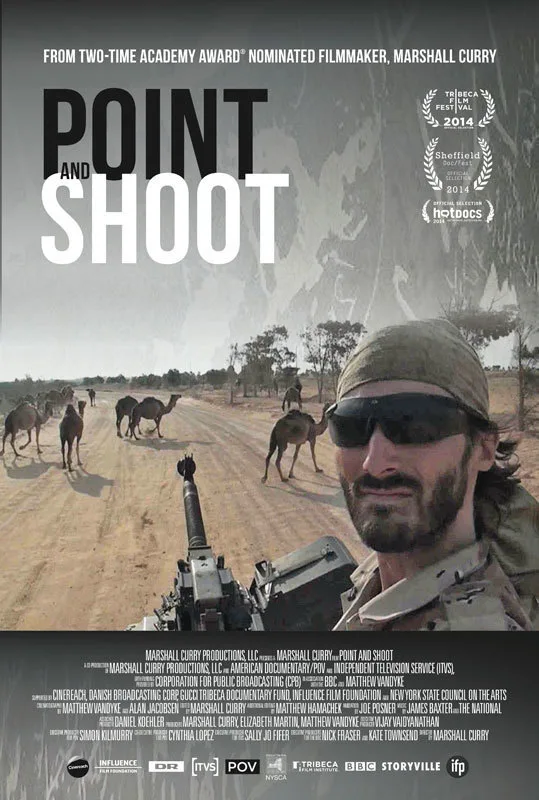

In the new war documentary “Point and Shoot,” filmmaker Marshall Curry provokes viewers with a loaded question: did Matt Van Dyke do the right thing? Van Dyke is an American civilian who set out to document his backpacking adventures across Africa, and wound up becoming a symbol of the Libyan revolt against Muammar Gaddafi’s oppressive regime. Curry periodically reminds viewers that he’s at least a smidge skeptical of Van Dyke by tentatively questioning his motives, like when he asks Van Dyke what he thinks of people who will say he should have fled Libya after being imprisoned by Gaddafi loyalists for six months. But more often than not, Curry doesn’t give us much to judge his subject by beyond anecdotal details and non-committal introspection.

Van Dyke explains that his travels through Libya were a way of refashioning himself as a rugged adventurer. “Everyone creates their idealized image of how they want to be seen,” he demurs. This is an inherently troubling position to take, since real-life violence isn’t the same thing as the “Sid Meier’s Civilization” computer games we see Van Dyke playing. Van Dyke acknowledges that by stubbornly qualifying some of his more incredible assertions, like when he defensively adds “I cannot imagine staying at home, watching my friends being killed” after insisting that “the Arab spring…[challenged] what I knew was to be a man.”

Curry gently guides Van Dyke’s narrative throughout “Point and Shoot,” asking him to think about where his pre-revolutionary ideas of heroism came from, and why he chose to pick up arms, and fight. But he’s usually so obsessed with establishing the broad structure of Van Dyke’s self-made man narrative that he rarely takes time to flesh out its more tantalizing details. For example, we don’t really know why Van Dyke renames himself “Max Hunter,” or why he describes his Hunter persona as a “swaggering, egotistical” counterpoint to his usual anxious, meek self.

Moreover, while Van Dyke characterizes his pre-Libya personality through anxieties, we don’t learn what motivated them. This is partly because he suffers from at least one Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Van Dyke is not only highly germophobic, but also perpetually fearful of hurting other people. Curry doesn’t press Van Dyke on this last point, preferring instead to focus on the fact that Van Dyke wanted to conquer his fears by documenting his journey across Africa with a video camera mounted on his motorcycle helmet. So Van Dyke tells us of his interest in “Lawrence of Arabia,” but not what he loves about that film. He also doesn’t explain how, practically speaking, a seriously anxious person trains himself to live in “utterly filthy” hotels, to shoot guns, and to pal around with revolutionaries who constantly tease him about his outsider status.

“Point and Shoot” consequently feels like a film made by a storyteller—not a journalist—who doesn’t know he can ask follow-up questions. Curry understandably doesn’t judge Van Dyke so harshly that his status as a tourist looking for self-esteem ever seems malicious. But he also doesn’t mine enough experiential details from his subject to explain his

transformation into the second coming of John Rambo. So while Van Dyke insists that he has a deep sense of respect to the friends he made while growing a wicked beard and fighting for his life, it’s impossible to know what he’s feeling when one of his comrades jokes that he’ll send Van Dyke’s body home in a posh coffin, as a “nice souvenir” for his mother.

Even the moviemaking-as-self-fashioning angle that Curry leans hard on throughout “Point and Shoot” is underdeveloped. Curry uses his talking head interview footage to simplistically create a pattern that unites Van Dyke’s first impression of Gibraltar—”It was very picturesque…it was how I would have imagined it in a script”—with American soldiers’ requests to be filmed posing heroically with their guns, and best tough guy glares. But Curry doesn’t get his subject to explain why he thinks these requests are just soldiers asking for Facebook post-ready clips of them doing what they do, or why he told his Libyan allies that he wanted to be more than “just a cameraman,” insisting that, as one ally puts it, he be a soldier with “two [full] hands: guns and camera.”

Since “Point and Shoot” isn’t a political documentary, but rather a narrative about stories, Van Dyke’s memories of imprisonment are especially disappointing. This scene should feel revelatory since, as he says, “It absolutely transformed me.” But these scenes, represented through imagistic animated flashbacks, aren’t especially moving. They suggest a stir of emotions without evoking them, emphasizing POV shots of disembodied hands, and the night sky as seen through Van Dyke’s pinhole-sized air hole. Curry’s not patient enough to get inside his subject’s head, so “Point and Shoot” often feels as rushed as its title implies.