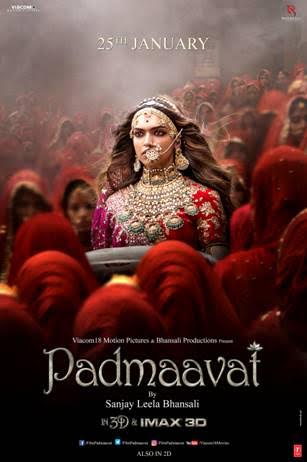

The three-star rating that I’ve given to the equally thrilling and upsetting Indian period spectacular “Padmaavat” does not reflect my personal disagreement with the film’s politics. A review’s star rating is usually supposed to be a holistic approximation of a critic’s response. But “Padmaavat,” a controversial adaptation of Malik Muhammad Jayasi’s 16th century epic poem, is a different kind of film, and it needs a different sort of review/rating.

“Padmaavat” is, after a certain point, propaganda for a pseudo-traditional and highly romanticized fundamentalist attitude. It is possible to enjoy most of the film without asking yourself why this 11th-century-set drama was made, particularly during scenes where the mild-mannered King Ratan Singh (Shahid Kapoor) and his head-strong queen Padmavati (Deepika Padukone), the rulers of the small kingdom Chittor, try to stop greedy Sultan Alauddin (Ranveer Singh) from abducting Padmavati. But the real trouble starts in the film’s final stretch: “Padmaavat” hinges on a dramatic act of of “jauhar,” the Hindu ritual where women threatened by rape and/or enslavement set themselves on fire.

When considering how to review and rate “Padmaavat,” I thought of other milestone period dramas that were this ideologically extreme, like “The Birth of a Nation” and “The Passion of the Christ.” Those earlier films also seemed designed to appeal to a hypothetical like-minded choir who already shared the filmmaker’s point-of-view on the subject. “Padmaavat” is likewise a passion project. Its main appeal stems from its seductive rhetoric. It tries to draw you in and make you see the world through the eyes of its main characters, to better understand the appeal of values that many consider outdated. The movie is a powerful explosive with a very long fuse. “Padmaavat” is, in that sense, exactly the kind of movie that writer/producer/director Sanjay Leela Bhansali (“Black,” “Saawariya”) set out to make, so I want to try to judge how successfully he and his collaborators convey the story’s ideas, apart from the blatant provocation of its ending.

Bhansali implicitly extols questionable concepts of femininity, loyalty, and spirituality, even if “Padmaavat” is more concerned with secular traditions than religious beliefs. Still, try telling that to the right-wing Hindu rioters who, according to Reuters, took to the streets of New Delhi last week to protest the film’s depiction of a Muslim Sultan trying to seduce a Hindu queen who has come to symbolize purity, and inner strength. It’s hard to imagine being able to talk about this film, or its characters’ symbolic importance without getting into a fight about its inherently retrogressive nature. The Huffington Post India’s Betwa Sharma notes that the film exposes a raw nerve during her conversation with Indian school-teacher Rakhi, who says that she cannot begin to talk to her family about why she dislikes treating Padmavati as a positive role model: “[My family] said that ‘you are anti-national, anti-Hindu and a disgrace to your caste … “

Still, “Padmaavat” seems to exist to show the beauty of Jayasi’s archetypal love story. Through several key scenes, we watch as Bhansali emphasizes Alauddin’s secular greed and obsessive character. Singh’s intensely committed performance makes you believe in his character’s Iago-like malevolence, even when Singh himself goes so far over the proverbial top that he flies into the stratosphere. Singh’s charisma makes you believe him when he snarls, grimaces, and even dances out Alauddin’s character-defining aggression. Singh’s dancing is especially impressive, as in the scene where Alauddin gathers his men and boasts that he’s “aloof before heaven.” This setpiece is so rousing that it stands out as the best musical number in a film full of strong vocal performances and well-conceived choreography.

Bhansali also makes Padamavati and Rhatan Singh’s relationship look strong enough to be attractive. She does inevitably ask him for permission to kill herself. But that choice feels like a decision that her character would make based on her previous actions. Bhansali convincingly sells Padamavati’s perspective in scenes like the one where she defiantly tells Rhatan Singh’s treacherous Brahmin adviser what she believes: that “happiness” in a relationship depends on mutual trust, and personal “sacrifice” is only possible when you believe that your physical body is a fleeting expression of your self. Bhansali uses similarly fraught but relatively innocuous scenes to make inflexible characters seem affable and attractive. Consider the scene where Rhatan Singh and Padamavati celebrate the spring festival of Holi by dying each other’s faces and ankles with brightly colored powders. It’s a genuinely sexy and tender sequence, and it makes you believe that the couple’s uneven power dynamic is more level than it really is.

Still: even if you admire the film’s craft, what can be said to a viewer incensed at the idea of a woman using self-immolation as a means of standing up for herself? Nothing. I sympathize and share the feelings of actress Swara Bhasker when she asserts, in an open letter to Bhansali, that “Women have the right to live, despite the death of their husbands, male ‘protectors’, ‘owners’, ‘controllers of their sexuality’… whatever you understand the men to be. Women have the right to live—independent of whether men are living or not.” I also confess that Bhansali momentarily convinced me that, within the context of his drama, Padmavati’s representative actions reflected her inner strength. “Padmaavat” is a rare work of pop art that is both powerful and repugnant.