How seriously does “Orphans” intend to be taken? On one hand it tells the gritty story of three brothers and their handicapped sister in Glasgow, Scotland, in the 24 hours after their mother dies. On the other hand, it involves events that would be at home in a comedy of the absurd. When the sister’s wheelchair topples a statue of the Virgin Mary and the damage is blamed on high winds that lifted the roof off a church, we have left the land of realism.

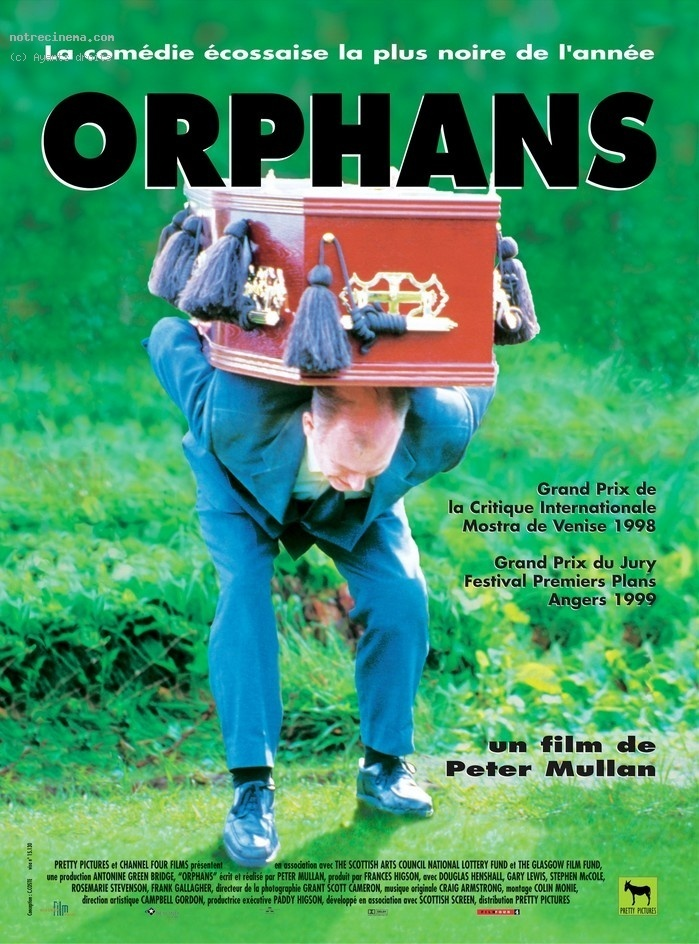

We have not, however, entered the land of boredom. “Orphans” is a film of great intensity and weird events in which four suddenly parentless adults come unhinged in different ways. For Thomas, the oldest, the mother’s death is an occasion for piety, and he spends the night with her coffin in the church and later tries to carry it on his back to the grave. For Michael, it’s an occasion for boozing, a pub fight and a spiral of confusion after he gets knifed. For John, the youngest, it provides a mission: to find and kill the man who stabbed Michael. And for Sheila in the wheelchair, it leads to an act of defiance as she ventures out into the night alone.

The movie, part of the six-film Shooting Gallery showcase at the Fine Arts and Evanston theaters, was written and directed by Peter Mullan. You may remember him as the title character in “My Name Is Joe,” Ken Loach’s heartrending film about a recovering alcoholic in Glasgow. He won the best actor prize at Cannes for that role, and with “Orphans” focuses on at least two characters in urgent need of Alcoholics Anonymous.

It’s one of those sub-Eugene O'Neill family dramas in which a lifetime of confusion and anguish comes to a head during a family crisis. We see how each brother has hewn out his space in the family in reaction to the others, while the sister basically just wants out. The brothers Michael and John inhabit a world of hard characters and pub desperados (sample dialogue: “We’d cut your legs off for 20 Silk Cut [cigarettes] and a rubber bone for his dog”). Thomas likes to see himself as older, wiser, saner, more religious, and yet he’s the maddest of them all. And the movie staggers like its drunken characters from melodrama to revelation, from truth-telling to incredible situations, as when Michael finds himself used as a dart board by a pub owner.

How are we to take this? There are times when we want to laugh, as when Thomas tries to glue the shattered Virgin back together with hot wax candle drippings (“She’s a total write-off,” he observes morosely). We see the roof lifting off the church in a nice effects shot, but why? To show God’s wrath, or simply bad weather conditions? It’s a nice point when the funeral goes ahead inside the ruined church–but wouldn’t the insurance company and public safety inspectors have something to say about that? Maybe we’re not supposed to ask such realistic questions, but we can’t resist. Yet other moments seem as slice-of-life as anything in “My Name Is Joe.” My guess is that Mullan never decided what tone his film should aim for; he fell in love with individual sequences without asking how they fit together. The Shooting Gallery series includes an optional “club night” when members get to discuss each film with a movie critic, and here, it must be said, is a film that provides a great deal to be discussed.

Note: Because of the characters’ Glasgow accents, the film has been subtitled. But we can understand most of what the characters say, and that leads to disconnections, since the subtitles are reluctant to use certain four-letter Anglo-Saxonisms we can clearly hear being uttered by the characters.