In a poem called Home Burial, Robert Frost wrote, “from the time when one is sick to death/One is alone.” Those who are critically ill pass through the stages unforgettably defined by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. And they do it alone. Those around them, no matter how loving and how devoted, pass through their own stages. They face fear, grief, helplessness, compassion, loneliness, survivor guilt, exhaustion, and the guilt of feeling angry at the one who is dying. But they can never truly understand the experience of facing death, of seeing one’s old life from the other side of an impenetrable glass wall.

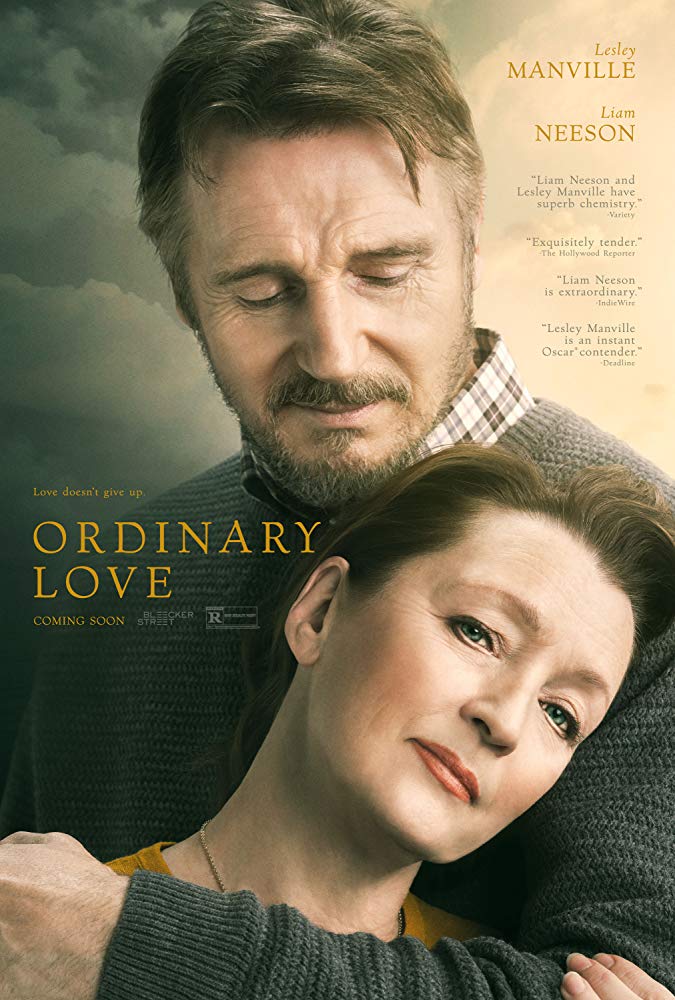

“Ordinary Love” stars Liam Neeson and the exquisite Lesley Manville in the story of a couple who are navigating the world of serious illness, the euphemisms and delays, from initial tests that are “concerning” to the diagnosis: “the results weren’t what we hoped.” Then there is surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Health care professionals are sympathetic but removed. Random encounters with other patients somehow become vitally important.

This first screenplay by Irish playwright Owen McCafferty is inspired by his own wife’s experience with breast cancer, and the smallest details are thoughtfully observed and portrayed with sympathetic honesty. Tom (Neeson) and Joan (Manville) have an amiable, affectionate relationship with a lot of gentle teasing that may sound like bickering but is really their form of banter, clearly honed over decades together. Her name may be a reference to Darby and Joan, a popular British term from an 18th century poem that has come to mean any unassuming (“ordinary”), long-time married couple who are deeply devoted. In the poem’s terms, they are “ever uneasy asunder.”

Uneasy and asunder is what Tom and Joan are about to be. In the shower, Joan feels a lump in her breast. Her last mammogram, eight months earlier, was clear, so the doctor’s initial response is reassuring. But there must be tests, just to make sure. The results are not good. As they move forward, even the “good” results are not very good, and the treatments are brutal.

Joan spots a familiar face in the hospital waiting room. It is Peter (David Wilmot), another cancer patient. He was a teacher who once had Joan’s daughter Debbie in his class. McCafferty understands the instant straight-to-the-point intimacy of fellow patients and the comfort that they get from being able to be frank with each other. Joan and Tom are completely comfortable with their companionable but indirect form of communication. Peter and Joan speak with the kind of directness that only comes when time is limited and choices are even more limited.

McCafferty shows this in even the briefest of encounters, as with a fellow patient who gives Joan some advice on chemo. Later, another patient preparing for her first treatment gives Joan the chance to pass on that sympathetic reassurance, even as she looks at the young woman’s long hair, knowing what is to come.

Manville gives a performance of heartbreaking delicacy and courage. When her hair starts to come out in clumps, it is time for Tom to cut it all off and shave her head. Watch her face as she pretends—convincingly—to find it all funny as long as he is in the room. That same look fades away as she confronts the image in the mirror when she is alone. Joan and Tom pay a tender farewell to her breasts in a scene so intimate it is almost intrusive. Manville has to go through a kaleidoscope of moods and emotions, and every one of them is precise, fearless, and searingly real. There is nothing ordinary about Tom and Joan, and their story shows us that there is nothing ordinary about love.