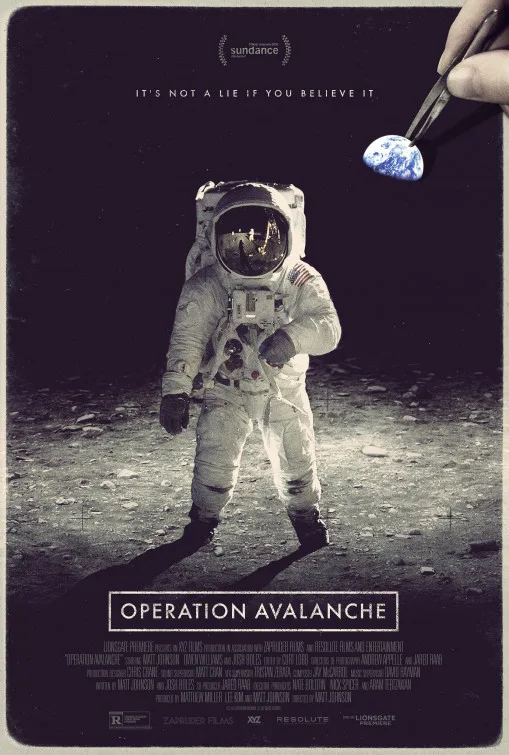

Found-footage conspiracy thriller “Operation Avalanche” is never as compelling as its high-concept premise: a quartet of CIA scientists help NASA fake the Apollo 11 moon landing after they discover that the Americans can’t land on the moon. This conceit is, on the surface, borderline offensive: why do we need to question the authenticity of one of humanity’s most awe-inspiring achievements? Matt Johnson and co-writer Josh Boles never try to address this thorny issue, though one of their characters does perfunctorily ask a colleague if he doesn’t think faking the moon-landing is “unethical.” Instead, Johnson and Boles ground their story in a fairly rote ticking-clock narrative: bland (but peppy!) protagonists struggle to complete their project in time as poorly-hidden spies lurk around every corner.

Paranoia abounds, but nothing sticks to agents Matt Johnson and Owen Williams, two of the most boring CIA agents you’re likely to ever meet. The most personal things that define these guys are their taste in period-specific films and music. Being cocky young men in the year 1967, Johnson and Williams blast Creedence Clearwater Revival when they’re happy, and paper their office with posters for “8 1/2,” “The Stranger” and “Lolita.” These cultural signposts stand out like a sore thumb, and are unfortunately the only clear indicator—other than cars and wardrobe—that “Operation Avalanche” is a period piece.

It’s also implied—and I do mean heavily implied—that these guys like to make movies. Two or three scenes show us Johnson and Williams at work doctoring photos and using Stanley Kubrick’s famous front-projection technique—a highly-reflective surface is used to project background images behind actors in order to create the illusion that they’re standing in front of a blown-up matte painting, or photograph—in order to make it seem as if they are on the moon. These guys are defined by their enthusiasm, or more accurately Johnson’s frantic need to prove himself, and Williams’s fraidy-cat need to avoid the wrong kind of attention.

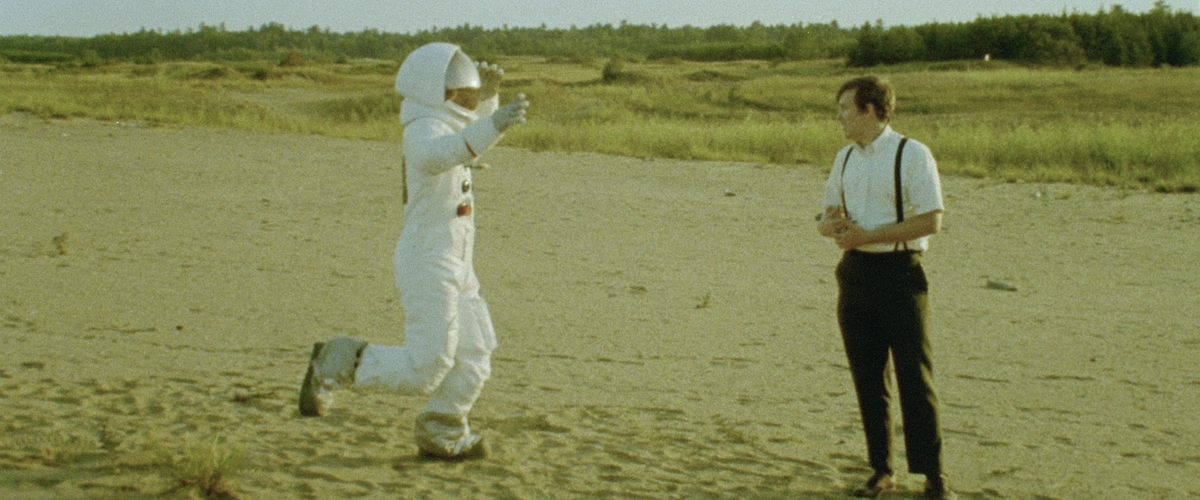

The most interesting scenes in “Operation Avalanche” half-heartedly address this basic shortcoming: we see Johnson and Williams using slow-motion photography to make it seem as if they’re bounding around on the moon (in the film’s reality, a remote desert location). We also see the two leads struggling to come up with an appropriate line for Neil Armstrong to say when he first steps on the moon—”a leap forward … for humanity”—but the less said about that unfortunately pandering exchange the better. Boles and Johnson rarely take enough time to show us what gets these guys going beyond an implied need to earn respect, or protect their families.

Instead of developing their characters beyond sketch-thin imperatives, the creators of “Operation Avalanche” focus on banal, effects-driven chase scenes and period re-enactments. Scenes where characters are shot at by blurry G-men driving a vintage Cadillac only call attention to on-the-cheap special effects. There’s no soul, nor any visual coherence in this type of scene. Which is to say nothing of the lack of internal logic behind scenes like the one where a Caddy driven by a spy tears away from the warehouse where Johnson and Williams are hard at work. Why would a spy—and it’s largely implied that it’s a spy since he hastily tears away when Johnson approaches him—park right outside of the warehouse’s entrance? There’s no good answer to that question, making it impossible to get lost in cheap thrills and lame historical speculation.

You know you’re in trouble with a film when you’re so bored by it that you wind up asking why things seem so implausible. The makers of “Operation Avalanche” make you wonder why Johnson keeps his clip-on mic all the time, or why one of his colleagues never stops filming him. The film’s narrative requires several leaps in logic, many of which are never really addressed given how focused the film is on Johnson and Williams’s story. They fight among themselves, and inevitably start to suspect each other of sabotage. But the paranoia these guys experience doesn’t appear to be rooted in the film’s Cold War setting. I had no sense that these characters cared about their country, or their mission beyond what it could get them. If that’s a statement on what it was like to live in the ’60s, it’s a vague, and poorly-expressed one.

I kept hoping that “Operation Avalanche” would eventually get so good that it would force me to overcome my innate skepticism. I didn’t need the film to do anything except make me feel something for these characters, or at least make me want to invest in their cover-up scheme. That moment never came, and I can’t help but feel that’s because Johnson and Boles didn’t do enough research on the type of characters who would, in the ’60s, leap at the chance to fake the moon-landing. You can only coast so far on a novel idea’s fumes, and “Operation Avalanche” doesn’t go far enough.