Back when I was a young and feckless Jersey guy driving around with my friends, we had a running joke about how many “points” applied to mowing down some dope who was crossing against the light or jaywalking directly into your car’s approaching fender. The more inappropriate or sacred the ostensible target, the higher the number of points. We did not make up this mordant joke—at least I don’t think we did. But we got a grim kick out of it, until we didn’t. (Mind you, we never actually hit anybody, or tried to!)

In contemporary urban China the value of a “kill” in a hit and run is not a joke, though. Hit and run accidents there are sickeningly common, and the consequences for the drivers who commit them vary in an equally sickening way. It’s not a point system—civilization hasn’t devolved that badly. But a driver who kills someone in a hit and run accident gets, as a rule, very little in the way of punishment. Whereas a driver who merely injures someone has to pay costs of medical care for the remainder of the victim’s life.

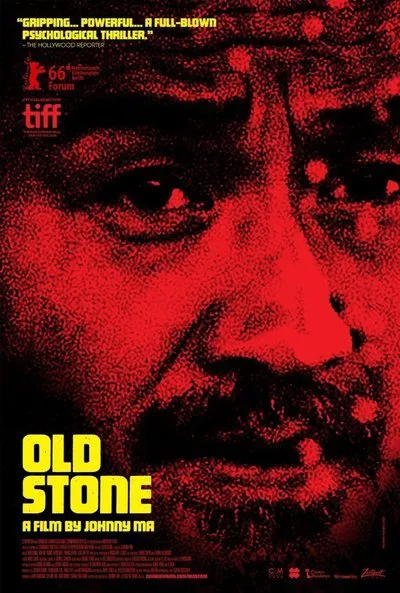

The way these peculiar rules practically affect human behavior is the subject of “Old Stone,” a concise but very knotty drama from director Johnny Ma, a Chinese-born, Canadian-raised and U.S.-trained filmmaker making his feature debut. The title character, whose name in Mandarin is Lao Shi—played in a superb and disciplined performance by Gang Chen—is a cab driver in a small city in the Anhui province who hits a cyclist after a drunken passenger grabs his arm, causing him to swerve. As the victim lies on the pavement, foaming at the mouth, Old Stone makes calls, awaits help, and tries to follow the seemingly all-important “procedure” people keep mentioning (and will continue to cite throughout). Sensing his victim may die, he takes the step of bringing him to the hospital himself. That’s when his troubles truly begin.

The victim is in a coma, and Old Stone has to pay the cost of his admission and care immediately. He then gets a hard time from everyone: the police, who want to know why he didn’t follow, you guessed it, “procedure”; his wife, who’s afraid, not without reason, that the situation will bankrupt their family; a lawyer who’s a family acquaintance, and so on. He eventually makes contact with the victim’s family. Turns out to be a bad idea. Old Stone manages to track down the drunk businessman who caused him to hit the victim in the first place. The sunny grin of hope that lights up Old Stone’s face as he meets this man who he thinks can help him is the only time you see the character smile. It’s a grimly heartbreaking sight, though, because you know this clown is going to bring him down and probably humiliate him while doing so.

People misuse the phrase “Kafkaesque” too often, but there is something like that in the dilemma Old Stone faces; actually, the situation is Kafkaesque in an inverted way. In Kafka’s world, the characters are harassed, persecuted and killed for being themselves; here, Old Stone feels driven to harass, persecute and perhaps kill because of his circumstance. Writer/director Ma handles the conundrums with brisk assurance, shooting the drama with a documentary realism that he punctuates with enigmatic views of forests undulating in the wind. By the movie’s finale, however, Ma overplays his hand.

The ending, while not inapt, also delves into a realm of cinematic overstatement that the movie had up until that time been careful to avoid. While disappointing, it doesn’t wholly mitigate the power of what has come before. This is an engrossing and unnerving film.