Neil LaBute’s “Nurse Betty” is about two dreamers in love with their fantasies. One is a Kansas housewife. The other is a professional criminal. The housewife is in love with a doctor on a television soap opera. The criminal is in love with the housewife, whose husband he has killed. What is crucial is that both of these besotted romantics are invisible to the person they are in love with.

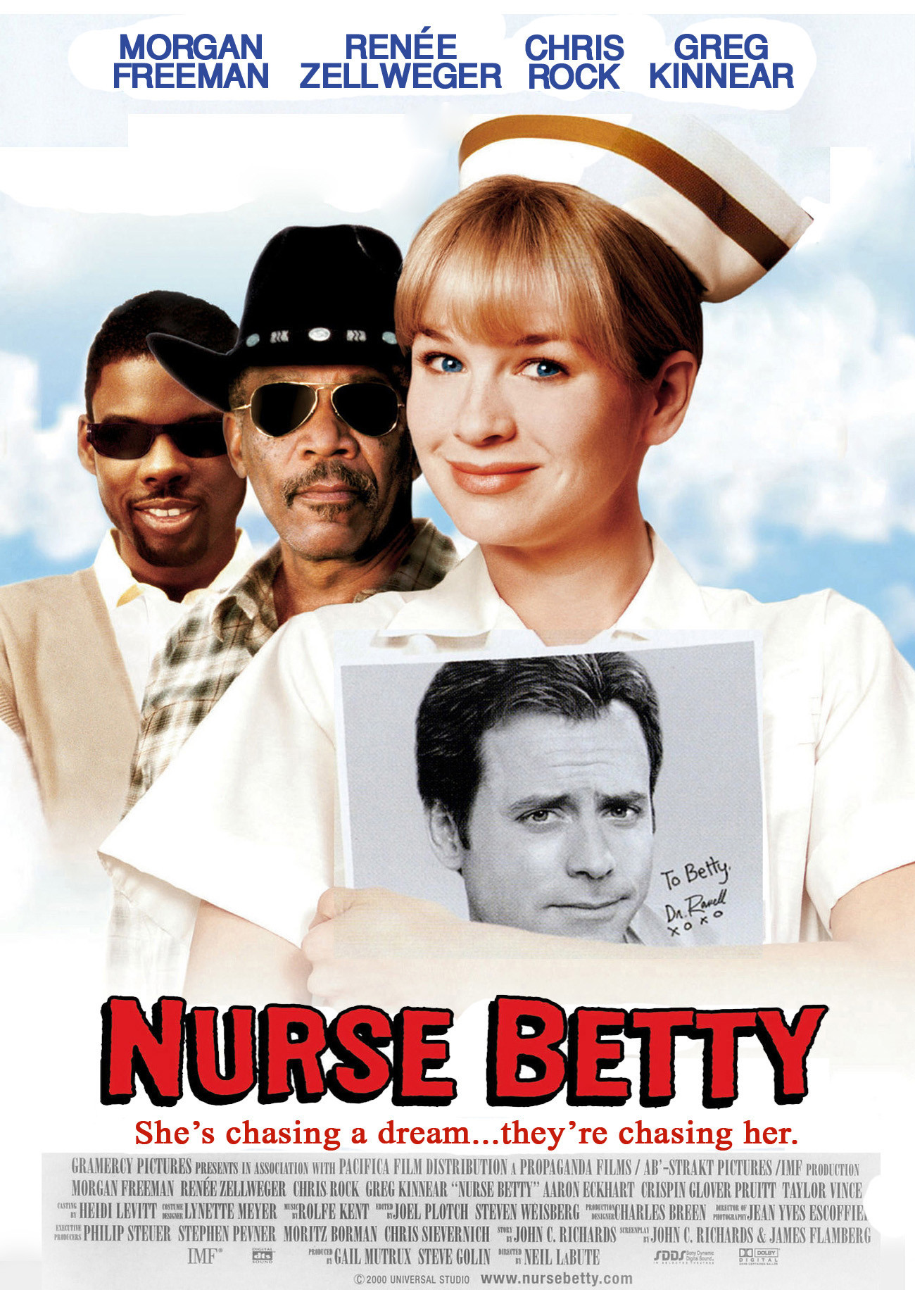

Morgan Freeman is Charlie, the killer, and Renee Zellweger is Betty, the housewife and waitress. Their lives connect because Del (Aaron Eckhart), Betty’s worthless husband, tries to stiff Charlie on a drug deal. Charlie and Wesley (Chris Rock) turn up at his house, threaten him, scalp him and kill him. Well, Charlie only kills him because Wesley scalps him–and then what are you gonna do? Betty witnesses the murder, but blanks it out of her memory. Her husband was a rat, she doesn’t miss him, and in her mind his death frees her to drive out to Los Angeles to meet her “ex-fiance,” a doctor on a soap opera. Charlie and Wesley trail her, and in the course of their pursuit, Charlie’s mind also jumps the track. Under the influence of Betty’s sweet smile in a photograph, he begins to idealize her–he speaks of her “grace”–and to see her as the bright angel of his lost hopes.

In Los Angeles, Betty meets George (Greg Kinnear), the actor who plays the doctor. She relates only to the character, and as she talks to “Dr. David Ravell” at a charity benefit, George and his friends think they’re witnessing a brilliant Method audition. Charlie and Wesley meanwhile arrive in Los Angeles with Charlie increasingly bewitched by fancies about Betty. When they started chasing her, she was an eyewitness to murder who was driving a car in which her husband had hidden their drugs. Now Charlie thinks of her more as a person who would sympathize with his own broken ideals.

I’m spending so much time on the plot of “Nurse Betty” because I think it’s possible to misread. When the film premiered at Cannes in May, some reviews didn’t seem to understand that Betty and Charlie are parallel characters, both projecting their dreams on figures they’ve created in their own fantasies. Look at this movie inattentively, especially if you’re looking for Hollywood formulas, and all you see is a mad woman pursued by some drug dealers, like a high-rent “Crazy in Alabama.” But it’s more, deeper, and more touching than that. Zellweger plays Betty as an impossibly sweet, earnest, sincere, lovable, vulnerable woman–“a Doris Day type,” as Charlie describes her. She has unwisely married Del, a vulgar louse who orders her around and eats her birthday cupcake. Her consolation is the daily soap opera about her fantasy lover Dr. Ravell. When Charlie and Wesley turn up, nobody knows she’s home. She glimpses the murder from the next room, and her response is to hit the rewind button for a crucial soap opera scene she’s missed. A therapist tells the local sheriff (Pruitt Taylor Vince) she remembers nothing; she’s in an “altered state–that allows a traumatized person to keep on functioning.” Betty heads west in the fatal Buick LeSabre with the drugs in the trunk, and outside a roadside bar she experiences a fantasy in which Dr. Ravell proposes marriage. Not long after, hot on her trail, Charlie pauses in the moonlight on the edge of the Grand Canyon and fantasizes dancing with Betty. Charlie has never met Betty, and Betty has never met the “doctor”; both of their dream-figures are projections of their own needs and idealism.

Morgan Freeman has a tricky role. His Charlie is a mean guy, capable of killing but looking forward to retirement in Florida after one last “assignment.” He has great affection for Wesley, a loose cannon, and tries to teach him lessons Wesley is not much capable of learning. Charlie has led a life of crime but has now gone soft under the influence of Betty, whose smile in a photo helps him to mourn his own lost innocence.

Betty is even further gone. Traumatized by the murder, she has no understanding that the soap opera is a TV show, and her first scene with Kinnear is brilliantly acted by both of them, as she cuts through his Hollywood cynicism with unshakable sincerity. Kinnear is deadly accurate in portraying an actor who has confused his ego with his training, and a scene where Betty is offered a role in the show is handled with cruel realism.

LaBute previously wrote and directed “In the Company of Men” and “Your Friends and Neighbors,” films with a deep, harsh cynicism. “Nurse Betty,” written by John C. Richards and James Flamberg, is a comedy undercut with dark tones and flashes of violence. Heading inexorably toward a tidy happy ending, LaBute sidesteps cliches like a broken-field runner.

As for Charlie, his final scene, his only real scene with Betty, contains some of Freeman’s best work. “I’m a garbage man of the human soul,” he tells her, “but you’re different.” He is given an almost impossible assignment (heartfelt wistfulness in the midst of a gunfight) and pulls it off, remaining attentive even to the comic subtext.

“Nurse Betty” is one of those films where you don’t know whether to laugh or cringe, and find yourself doing both. It’s a challenge: How do we respond to this loaded material? Audiences lobotomized by one-level stories may find it stimulating or confusing–it’s up to them. Once you understand that Charlie and Betty are versions of the same idealistic delusions, that their stories are linked as mirror images, you’ve got the key.