Roger Ebert’s belief that cinema is a machine that generates empathy applies to “Nocturama,” a French thriller about a group of teenage Parisian terrorists. As a work of political provocation—one that asks viewers to relate with kids who endanger, and murder innocent civilians—”Nocturama” is useless, since the politics, background, and motives of writer/director Bertrand Bonello’s young characters are not developed beyond a basic point. But Bonello (“Saint Laurent,” “House of Tolerance”) doesn’t seem to care about ideology or psychology. Instead, he focuses primarily on what his characters are feeling and thinking on the day that they bomb and/or set fire to multiple targets around Paris, and then hole up over night in a nearby mall.

The movie conveys the range of emotions and ideas that the characters experience through a series of elaborate flashbacks, several of which go back in time just a few minutes or seconds earlier, to relate what other characters were doing at pivotal moments. The filmmaker refuses to pigeonhole his protagonists with trite exposition. Instead, he relies heavily on visual cues and clipped, opaque conversations to relate both the limits of our knowledge and the depth of his subjects’ feelings. Bonello doesn’t coddle viewers, but he does give us a world of information conveyed simply, without heavy-handed commentary.

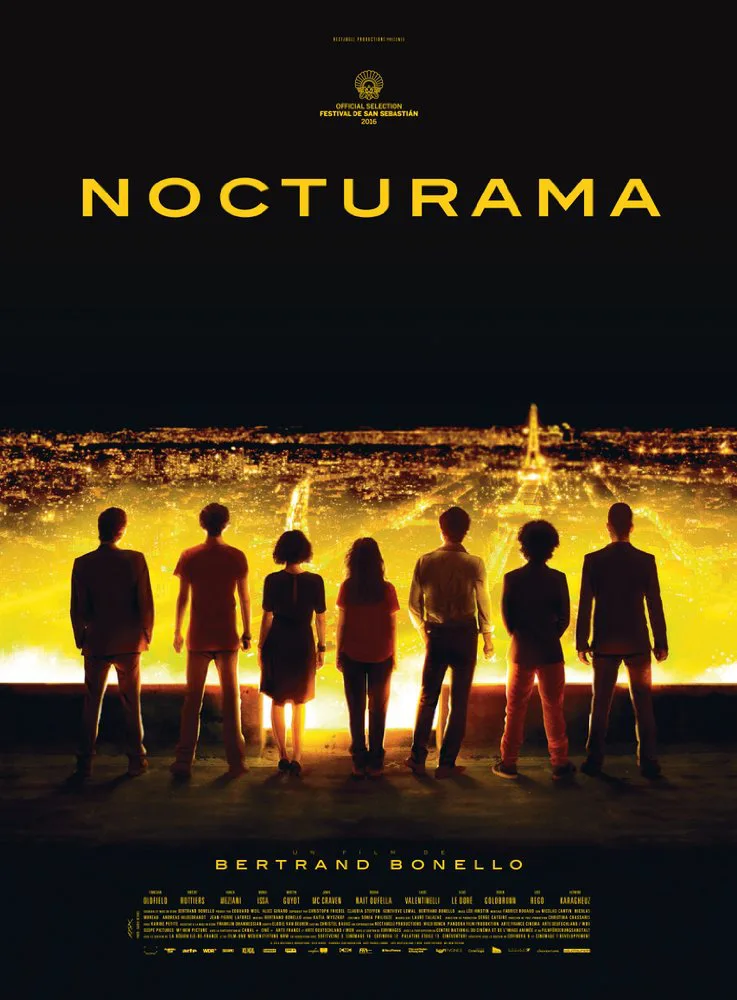

“Nocturama” starts on the afternoon of the never-named terrorist group’s attack. These kids have no clear leader, though no-nonsense Andre (Martin Petit-Guyot) comes closest. That said, they are hyper-organized, and very few of them show signs of hesitation. Each fulfills a role: Mika (Jamil McCraven) delivers an explosive while romanticallly involved couple David (Finnegan Oldfield) and Sarah (Laure Valentinelli) clear an office building’s 28th and 29th floor, which are already under construction. Meanwhile, Greg (Vincent Rottiers) keeps an eye out for security guards while Sabrina (Manal Issa) uses a cherry-picker to douse a statue of Joan of Arc in lighter fluid.

We don’t learn anyone’s names at first. They’re not important as individuals beyond the functions that they perform in the story. One swipes a credit card at a boutique clothing store and waits nervously for her purchase to be authorized. Others push their way past a security checkpoint using a counterfeit access card. Their colleagues ride the subway and try to act casual as they abandon cell phones in public trash cans, plant explosives, and check into hotel rooms under fake names. They are a well-oiled machine, momentarily working against a much larger system.

It’s never really clear why these kids behave the way they do. This might seem like a fundamental creative shortcoming, but Bonello makes it work to his advantage. Why pigeonhole these characters by allying them with a specific political ideology when you can let their actions—specifically their callow fascination with material goods, their love of rap and vintage pop music, and their giddy attraction to violence—speak for them? When these kids speak, they don’t talk for Bonello, or each other, but rather for themselves and to each other, and only in the moments that they’re speaking.

One boy believes he’s going to heaven. Another feels guilty and fears death. Several teens are hiding secrets from each other. These are not authority figures in adolescent bodies, but rather children who chose to rebel with an unthinkable act of violence. If “Nocturama” is a commentary about politics, it’s about the politics of avoidance, and the juvenile emphasis on being heard over having something essential to say.

Bonello is a master of blunt but simply expressed symbolism, and he often conveys the majority of his characters’ feelings through clipped, well-measured bits of naturalistic talk. Even flashbacks that threaten to editiorialize or hint at the real reasons why these kids did what they did are open to interpretation, as when one teen recalls a political history essay he wrote about how periods of decadence are always followed by a period of violent reconstruction and then by renaissances. The fact that he doesn’t dwell on cultural upheaval is telling. These kids are on auto-pilot, as evidenced by the way they clear out a mall by calling in a bomb scare and hastily dispatching the stores’ security guards, then carry on like kids in a candy store. They play with war toys, try on make-up, and perform karaoke for each other using expensive home entertainment systems. Mannequins surround them. The echoes of their footsteps haunt them. Designer labels accost them everywhere: dresses by Celestina Agostino. Bedding by Alexandre Turpault. Jewelry by Isabel Marant.

Bonello draws viewers in by letting circumstantial tension and quiet, private little gestures define the characters. We get to fill in the blanks when Mika dons a mask that obscures his facial features and looks at himself in the mirror. You can’t definitively know if he likes what he sees, or if he’s even thinking at all. We are also encouraged to draw our own conclusions when Omar (Rabah Nait Oufella) drives around a toy store in a child’s dune buggy. We follow him for a few moment as he careens around the display floor, periodically driving behind a plastic tarp that marks where the store ends and an employees-only area begins. This scene fragment tellingly ends with the dune buggy disappearing behind the tarp. Bonello knows exactly when he’s said just enough, and that makes the experience of watching “Nocturama” more engaging.

Despite how much information he purposefully withholds, Bonello’s film is remarkably accessible. We see these kids’ fears of being assimilated into a culture that only wants their blind allegiance. We see how they confuse counter-cultural influences as a separate kind of anti-system. Finally, we realize the limits of their knowledge and experiences, without the film feeling the need to overstate this. “Nocturama” engages critical thinking while it unassumingly works your emotions over. You may not think that a movie that asks you to understand terrorists is for you, but if you give Bonello 130 minutes of your time, he’ll make you a believer.