I confess to a flagging interest in the struggle between the forces of Light and Darkness. It’s like Super Sunday in a sport I do not follow, like tetherball. We’re told the future of the world hangs in the balance, and then everything comes down to a handful of hung-over and desperate characters surrounded by dubious special effects. I want to hear Gabriel blow that horn.

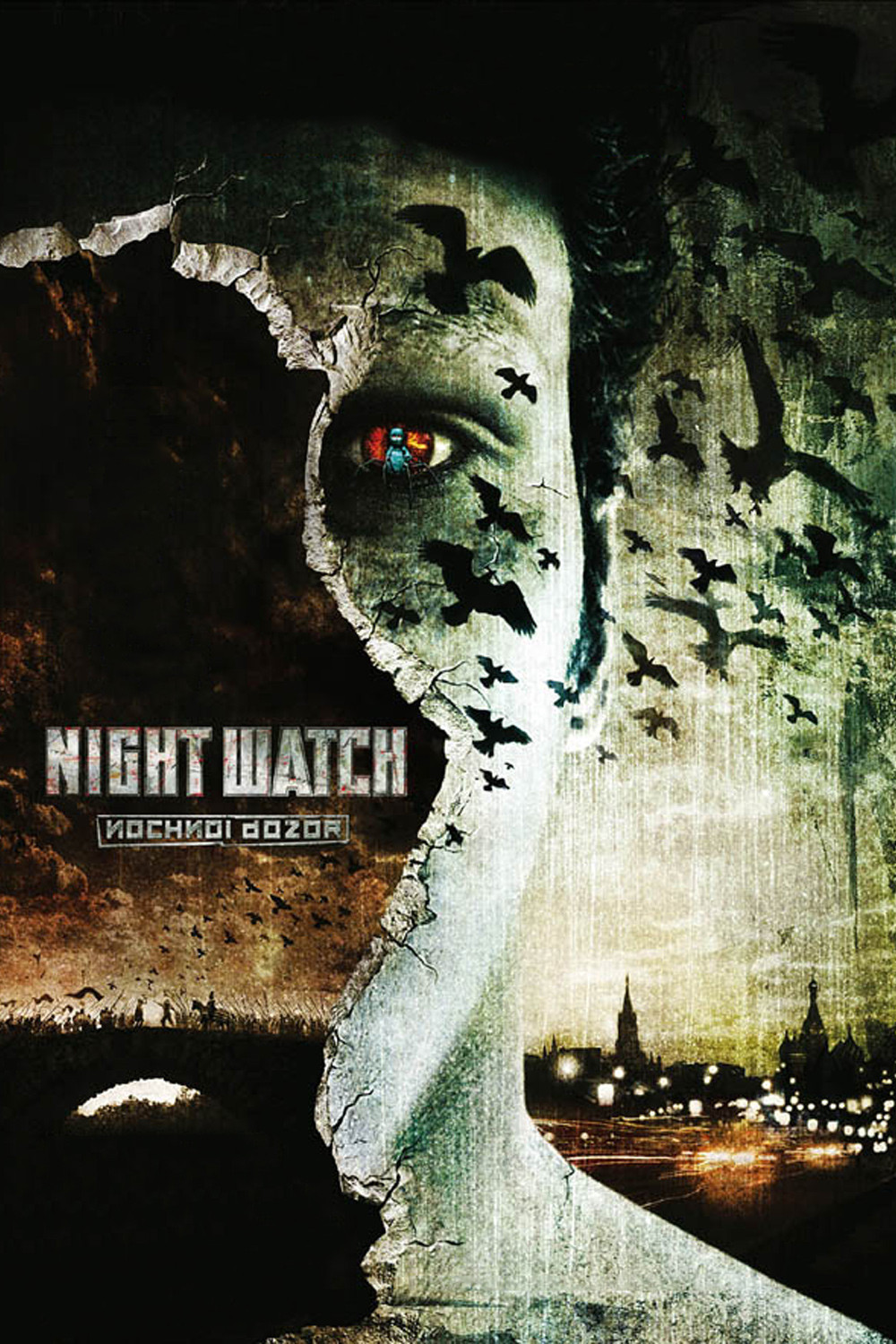

Movies about apocalyptic showdowns always begin with an origin story; the rules for the struggle were established long ago, but now a recent crisis has altered the balance. That’s the case with Timur Bekmambetov’s “Night Watch,” the first in a fantasy trilogy from Russia. We learn that in the year 1342, the Warriors of Light and the Warriors of Darkness met in battle on a bridge, and so bloody was their carnage that it appeared both teams of Others (so called, I think, because they are not Sames) would lose all of their warriors, which might have been a good thing for Earth in the long run. But it was not to be; Gesser and Vavulon, the leaders of Light and Darkness, establish a truce, which holds until Moscow 1992, when a new Other is born whose existence may reopen the ancient struggle.

We learn that during all the centuries in between, the truce was enforced; the Warriors of Light ran a Night Watch, and the Warriors of Darkness ran a Day Watch, to keep tabs on each other. Sometimes, when they were shorthanded, they hired a free-lancer from the other side, which is like trusting mercenaries because now they’re working for you. But now a young boy has been born who senses The Call and is drawn toward vampires — but hold on, how did they get in here? It appears that Others and Vampires are either interchangeable or operate in sync with each other, and the vampire hero Anton (Konstantin Khabensky), working for Light, attempts to rescue young Yegor (Dima Martinov) from the vampires of Darkness. Whichever team gets Yegor holds the edge. This is like Quidditch in hell.

You will sense that my understanding of the plot is not crystal-clear. Do not depend upon me for a rational synopsis. In the meantime, a Vortex is heading for Moscow, as symbolized by ground-level shots of special-effects birds whirling about the roof of a tall building. Severe turbulence seizes an airplane, and the power plant in Moscow blows up, throwing everything into darkness, and then Anton is savagely attacked , and brought into the office of the president of the light company, who sweeps everything off his desk and turns it into an operating theater to save him by plunging his fist into the chest of the victim, just like those magic healers we used to hear about in the Philippines.The Others are hardy; one warrior removes his own spine and uses it as a bludgeon. I wondered how he remained standing and had movement in his limbs, but it didn’t seem to bother him.

Let us return to the endangered airplane. The passengers scream, the plane plunges wildly through the air, and at one point is actually seen so close to the ground that it passes power cables. Then it’s left to bounce about forgotten by the plot, until a perfunctory shot shows it aloft again and cruising smoothly. That’s after the lights go back on in Moscow, which is odd, since how can the power plant function after it has exploded into smithereens? The movie is so plot-heavy, it scurries between developments like a puppy surrounded by pigeons. I cringe in anticipation of the e-mails explaining all of this to me; those who understand the plot of “Night Watch” should forget about the movies and get right to work on string theory.

One interesting quality of the film is its use of characters who seem as if they might actually live in Moscow. They have a careworn look. Most Light vs. Darkness movies involve elaborate wardrobes, as if, between Apocalypsi, the warriors refit at a custom leather shop. But the Others look scruffy, drink vodka and blood more or less interchangeably, and speed around the city not in a customized Vampiremobile but in a truck of the sort used to transport refrigerated meat. While indoors, they spend a lot of time in rooms that remind me of Oscar Wilde’s dying words: “Either this wallpaper goes, or I do.”

The subtitles for the movie rise to the occasion, literally. They do not simply materialize at the bottom of the screen, but unspool dynamically, dance across the picture, evaporate, explode, quiver and seem possessed. Not since a modern benshi version of the Mexican silent classic “The Grey Automobile” (1919) have I seen such subtitles. Benshis, of course, were the Japanese performers who stood next to the screen during silent films and explained the plot to the audience. If ever a benshi were needed in a modern movie, “Night Watch” is that film.