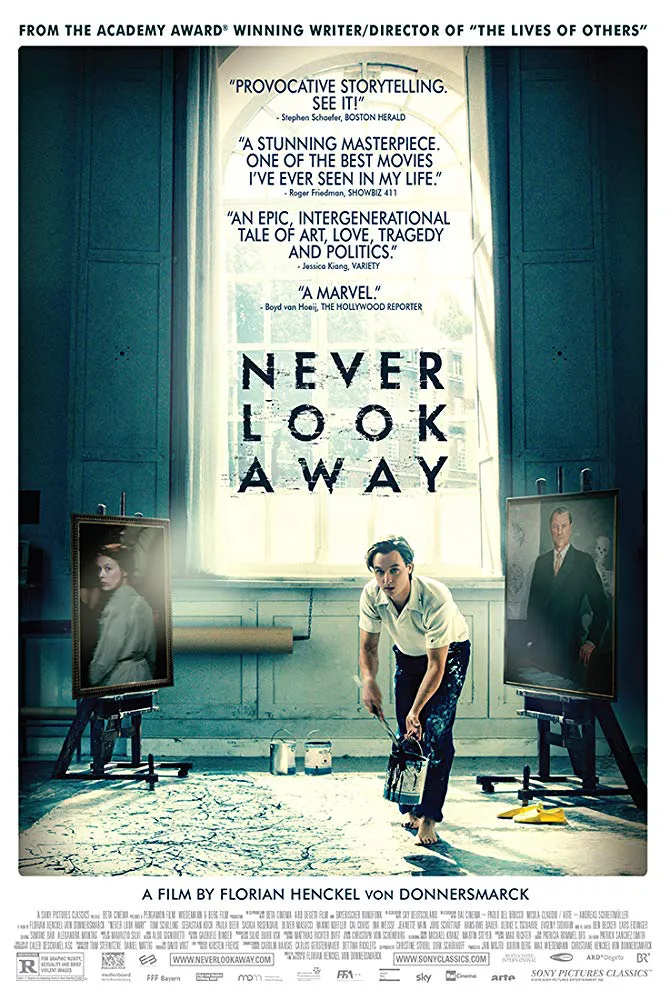

In 1937, the Nazi Party organized a notorious “degenerate art” exhibition, which opened in Munich before traveling through other German cities. Hitler had been railing against modern art for years (the artists were all “incompetents, cheats and madmen”), and so this exhibition was an extension of his attack on the modern world, on humanistic shared values. Featuring artists like Picasso, Mondrian, Kandinsky, Paul Klee, George Grosz, including an entire section devoted to Jewish artists, the exhibition was a propaganda blast against “impurities” in German culture. Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s new film “Never Look Away,” opens at this exhibit (it’s been transplanted to the city of Dresden). A small boy named Kurt (Cai Cohrs) and his free-spirited aunt Elisabeth (Saskia Rosendahl) stand in a group, listening to a tour guide (Lars Eidinger) sneer with contempt as he gestures at a Kandinsky: “How does this elevate the soul?”

This question reverberates throughout “Never Look Away,” a film spanning a 40-year period, and loosely based on the life of German painter Gerhard Richter, often referred to as the world’s greatest living painter. The boy’s “interaction” with art is interrupted by a world war, but—even more crucially—it’s impacted by warring political ideologies. First it was the Nazis, with their rejection of modernism, and then it’s the Communists after the war, when Socialist Realism is the only style allowed in the art school attended by Kurt (played as an adult by Tom Schilling). The Communists were as unforgiving as the Nazis in their attacks on artistic expression. At a daunting 188 minutes long, “Never Look Away” takes its time, doesn’t force its themes. Like one of those novels that follows a family through multiple generations, “Never Look Away” follows Kurt from Dresden, to Düsseldorf, to Berlin. It details his romance with fashion student Ellie (Paula Beer), and his difficulties with Ellie’s parents (to say more would constitute spoilers). All of this is overlaid with an awareness of the damage done by the top-down enforcement of ideology, how a society set up thus has one principle only, to destroy the individual’s will and spirit. Larger questions come up. How does a country that was run by Nazis transform itself into a Communist Utopia, with the same people who shouted “Heil Hitler” now declaiming the glories of Socialism?

“Never Look Away” covers a lot of ground, starting with a terrifying portrait of the Nazi’s eugenics and forced sterilization program, when aunt Elisabeth—the fragile and open-faced woman we saw in the first scene—is taken to an institution after a mental breakdown following being chosen to hand “The Führer” a bouquet of flowers at a local parade. (It’s an astonishing sequence.) Elisabeth is put under the “care” of a famed gynecologist, Professor Carl Seeband (Sebastian Koch, in a chilling performance), who schedules her for sterilization. Elisabeth vanishes from the film, but her memory lingers, a ghost flickering on the periphery of Kurt’s consciousness, barely remembered, but present. You could even say she was the wellspring of his art.

“Never Look Away” keeps its eye on the particulars, and in so doing critiques the messed-up society of totalitarian East Germany. (“The Lives of Others,” Henckel von Donnersmarck’s 2006 Oscar winner for Best Foreign Film, also starring Sebastian Koch, did a similar thing, wrestling with East Germany’s Stasi past by focusing on an intimate story of two artists under surveillance.) Through the character of Professor Carl Seeband, “Never Look Away” stares unblinkingly (speaking of the film’s title) at those who helped the Nazis implement their murderous policies, and then had to reinvent themselves into good Socialists following the war—either that, or flee from possible persecution for war crimes.

The more I think about “Never Look Away,” the more I think about it in terms of what it has to say about art and artistic expression, especially for those living in a totalitarian society. Art is always in the crosshairs. Art must be controlled: what can and cannot be said, as well as how things must be said. Ideologues demand that art should be uplifting, art must carry the ‘correct’ message, art must abolish ambiguity. What on earth would happen if artists were free to make the art they want to make? What would happen if it were left up to the viewer to decide the meaning? To quote Dr. Venkman in “Ghostbusters”: “Human sacrifice, dogs and cats living together … mass hysteria!” Kurt does his best to fit in. In the GDR art school, he paints women in kerchiefs holding up sheaves of wheat, men standing in wide-legged stances staring off at the horizon, idealized images of a Workers’ Paradise. He is praised. He becomes famous. But at what cost? What would happen if he splattered paint across a canvas like Jackson Pollock? What is so dangerous about that?

Gerhard Richter himself is thanked in the end credits. Knowledge of Richter’s specific journey is not necessary to understand “Never Look Away,” although familiarity with his art—and how it eventually developed (he’s been working for an extraordinary six decades)—probably will intensify the pleasure of the second half of the film, when his unmistakable style starts to emerge, almost by accident. In 2002, a friend and I went to a show of Richter’s art at MoMa, the first major exhibition of his work in America. Known for his blurred “photo paintings,” Richter never aligned himself with a specific movement (and, seeing “Never Look Away,” it is clear why). His paintings flicker like a mirage. If you glance at one quickly, you may see a photograph, but on closer inspection, the image dissolves into grey and white and black strokes. But sometimes the experience is in reverse. His work is difficult to absorb. The paintings are optical illusions, in a way, but the effect goes deeper than just a trick of the eyes. The impact of his work is intensified since his paintings are generally so big. The subject matter is sometimes explicitly political, like “September,” or his “October 18, 1977” series, which depicts members of the Baader-Meinhof Group. But then there’s something like “Motor Boat,” one of my favorites, showing three people in a boat, smiling at the “camera,” the water’s wake churned up behind them. “Motor Boat” captures a fleeting moment in time, you can almost hear their laughter and the roar of the motor. Richter’s work is all about the act of seeing, and what it means to look.

Some people will say “Never Look Away” is too long. Maybe. Maybe there are some sequences that could be trimmed. But much would be sacrificed, and there’s something very gratifying about watching an artist discover what he wants to say and how he wants to say it, even when cramped by the society in which he lives. There will always be ideologues who will demand of artists: “How does your art elevate the soul?” Sometimes the best thing to do is ignore the question.