Here’s a case of two actors who do everything humanly possible to create characters who are sweet and believable, and are defeated by a screenplay that forces them into bizarre, implausible behavior. It is not even the behavior I object to; in a raucous sex farce, it would be understandable. It is the film’s refusal to come down on one side of the fence or the other: to find a tone and believe in it. It wants to be heartfelt and sincere and vulgar, dirty and shocking. And it is willfully blind to human nature.

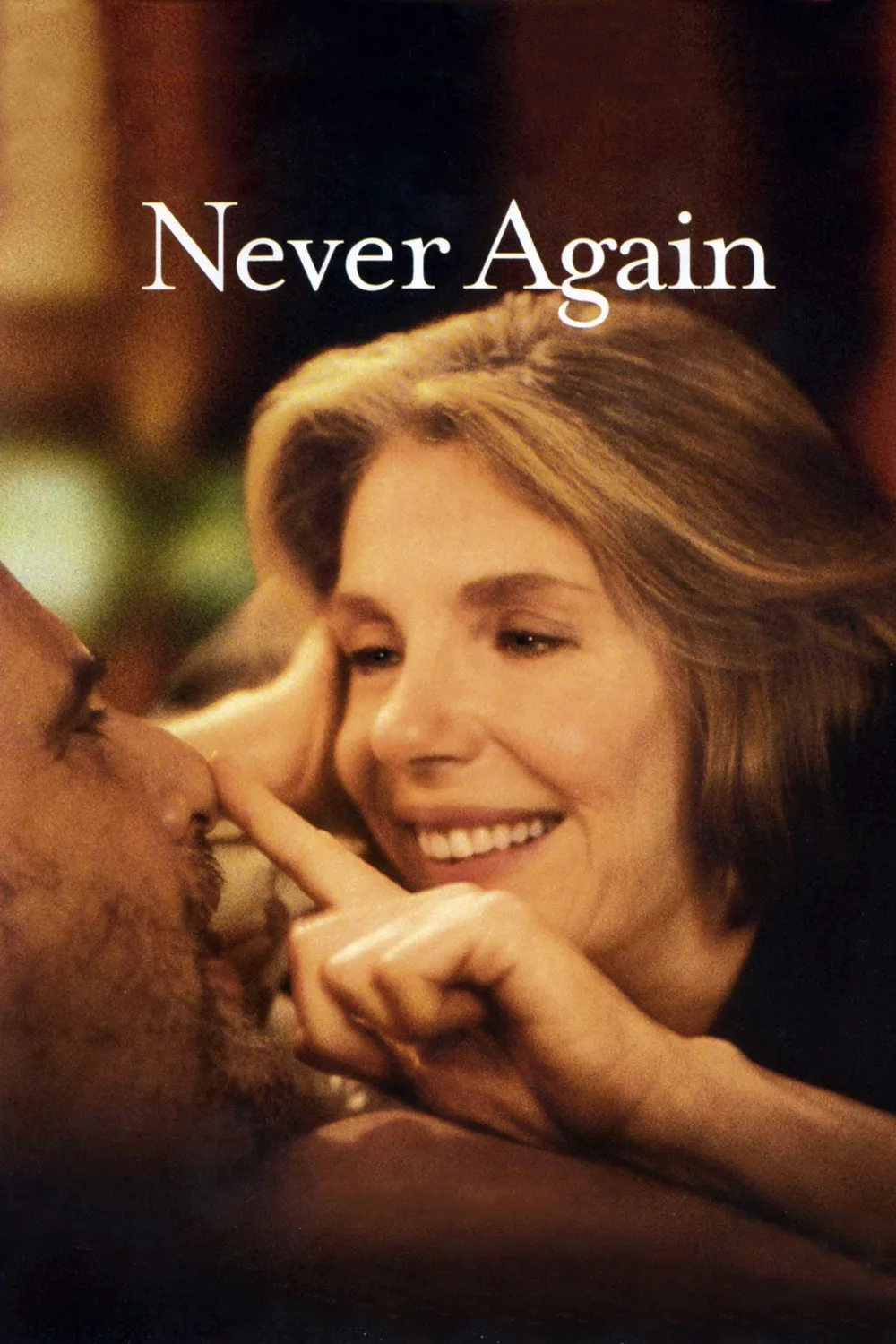

“Never Again” stars Jeffrey Tambor and Jill Clayburgh as Christopher and Grace, two lonely people in their 50s. She is divorced; he has never married. They both believe another romance is probably impossible. During the course of this film they will Meet Cute and have a relationship that no two people have ever or will ever have, outside the overheated imagination of Eric Schaeffer, the film’s writer and director.

Christopher runs an exterminating service by day and in the evenings plays jazz piano in a Greenwich Village night club; the combination of those two jobs says more about an overwrought screenplay than about employment possibilities in the real world. You might assume a jazz pianist in the Village would have seen something of life and even gathered some knowledge of homosexuality, but Christopher is as naive as a 13-year-old, and wonders if perhaps his failure to form relationships with women is because he is gay. To test this theory, he makes a date with the least convincing transsexual in cinematic history (Michael McKean), and then, fleeing the scene but still in an investigative mood, he enters a gay bar and meets the most unconvincing male hustler in cinematic history–before eventually trying to pick up Grace, who he thinks might be a more convincing transsexual.

She is a woman, she informs him, and has simply fled to the nearest bar after an unhappy experience in her own dating career. They decide to go out for a meal, and show in a few brief scenes that a sane and plausible version of this relationship might have made a wonderful movie. But no. Schaeffer wants it both ways, and has written a screenplay that periodically runs off the rails.

The most unlikely scenes involve Clayburgh’s eagerness to make up for lost time in the department of sexual experimentation. She walks into a sex shop to buy an enormous sex toy, and also walks out with whips, chains and what I guess is supposed to be an S/M uniform, although why a complete set of medieval armor would be necessary is beyond me; how about something simple, in leather or rubber? The appurtenance later pays off, so to speak, in a scene where she straps it on and can’t get it off when Christopher unexpectedly comes calling with his mother. I do not pretend to know if it could possibly be true that she could not remove the offending device, but there is one thing as certain as the sun in the morning, and that is that no 54-year-old woman would open the door to her boyfriend and his mother while wearing such an appliance, however well-concealed by a bathrobe.

There is another scene in “Never Again” that strikes a false note. Grace walks into a beauty parlor and describes an impressive array of sexual practices in a voice clearly audible to other women in the shop, whom she does not know. I am prepared to believe that a woman will tell her hairdresser anything, but that same instinct informs me that such women speak in hushed tones, because they don’t want everyone in the shop to spread gossip about events usually found in the pages of Penthouse Forum, if indeed that publication still exists. (“An interesting thing happened the other night between me and my boyfriend, a piano-playing exterminator …”) All of this is discouraging because in scene after scene, Clayburgh and Tambor show themselves ready and able to create Grace and Christopher as realistic characters. There is a remarkable scene where it appears that he’s about to break up with her, and she lets him have it, in a merciless verbal dissection; it’s a reminder of Clayburgh’s gifts as an actress. And other scenes where his loneliness is a fact instead of a set-up for gimmicks. But “Never Again” plays like a head-on collision between two ideas in conflict. Is it a movie about people, or about gags? What purpose is there in creating believable people, only to put them into situations that clash and jar? Who’s in charge here?