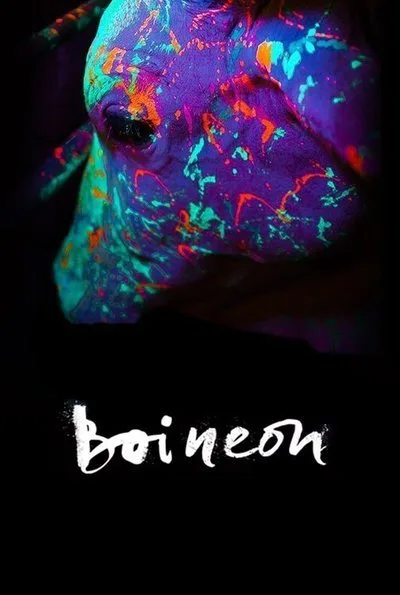

The latest example of what I call an emperor’s-new-clothes film is “Neon Bull,” by Brazilian director Gabriel Mascaro, which escorts us into the world of northeastern Brazil’s vaquejada rodeos. It was a buzz-generating hit at last fall’s Venice and Toronto festivals, and it does have one inarguable strength: a kind of anthropological interest, which is rendered with what one must assume is certain quotient of documentary-like accuracy. Mascaro mostly avoids the fleeing excitements of the bull ring in order to focus on a small group of characters who function as kind of a de facto itinerant family. Iremar (Juliano Cazarré) is a muscular and studly cowhand who devotes his off time to designing clothes, including skimpy stage outfits for exotic dancer Galega (Maeve Jinkings), a Shakira lookalike who drives the company’s truck and tends to her young daughter, Cacá (Aline Santana). The group’s other member is a corpulent cowhand named Zé (Carlos Pessao).

Still, its success may owe in part to the kind of exaggerated responses that festival premieres often provoke. And I would venture there are a couple of other potential causes that stem from the particular kind of festival film it is.

First, it’s the kind made outside of Europe and America but tailored for festivals in those places. Fans of international cinema who read accounts of premieres of a South American film at, say, Cannes may assume that said film was for made for the Brazilian market but happily discovered by discerning and venturesome French programmers. In reality, many of these films were created specifically for programmers and juries at international festivals, to whom they appeal by A) adapting the currently approved stylistic norms for “art” films, and B) viewing their native cultures in ways that will be seen as appealingly exotic by Europeans and Americans. (Whether you love or loathe their films, even estimable filmmakers such as Taiwan’s Hou Hsiao-hsien and Thailand’s Apichatpong Weerasethakul have become “world cinema” auteurs by employing this dual strategy.)

Second, “Neon Bull” is the kind of film that also bows strategically to other current cultural orthodoxies, specifically some rather dubious ones imported from academia. Consider the headline on The Hollywood Reporter’s review of the film, which determines that its “exploration of body and gender norms [makes] up for a lack of narrative.” Translated into plain English, what that means is: The film is essentially boring because its story is minimal and un-involving. But because its concerns can related to ‘body and gender norms,’ which university curricula now consider as important as previous centuries considered the Virgin Birth and Holy Trinity, it must be deemed important and meaningful.

Yet does the film have anything really cogent to say about those nominal subjects, or do the “body and gender” labels disguise something more pat and retrograde?

Mascaro spends much of the film’s length observing these characters as they sleep in hammocks and go about their daily routines. The characters are given no real depth—they’re types more than people—and the narrative has practically zero dramatic tension or development. There’s a general ambiance of sensuality which is upped a couple of notches when porky Zé is replaced by young, lean, long-haired Junior (Vinicius de Oliveira), and indeed the erotic intimations here are virtually the only things to sustain viewer attention.

Sex, almost by default, ends up being all the film has to sell. We get to see a horse being masturbated. And the climactic scene shows us Iremar’s erection as he mounts and has sex with a woman who’s nine months pregnant.

That’s all? Well, yes. That’s it. What does it say? That middle-class festival audiences in Europe and America derive a certain pleasure from watching sex scenes involving lower-class (and hence “naturally” sensual if not essentially animalistic) foreigners, as long as such prurient attractions can be described as exploring “body and gender norms”? No doubt. And the imperious cultural self-deception in that process would be laughable if it weren’t so sympathetic.