What a delicate dance they perform in “Nelly and Monsieur Arnaud.” It is a matter of great erotic fascination when two people are intrigued by the notion of becoming lovers, but are held back by the fear of rejection and the fear of involvement. Signals are transmitted that would require a cryptographer to decode. The difficulty is to send a message that can be read one way if the answer is yes, and the other way if the answer is no.

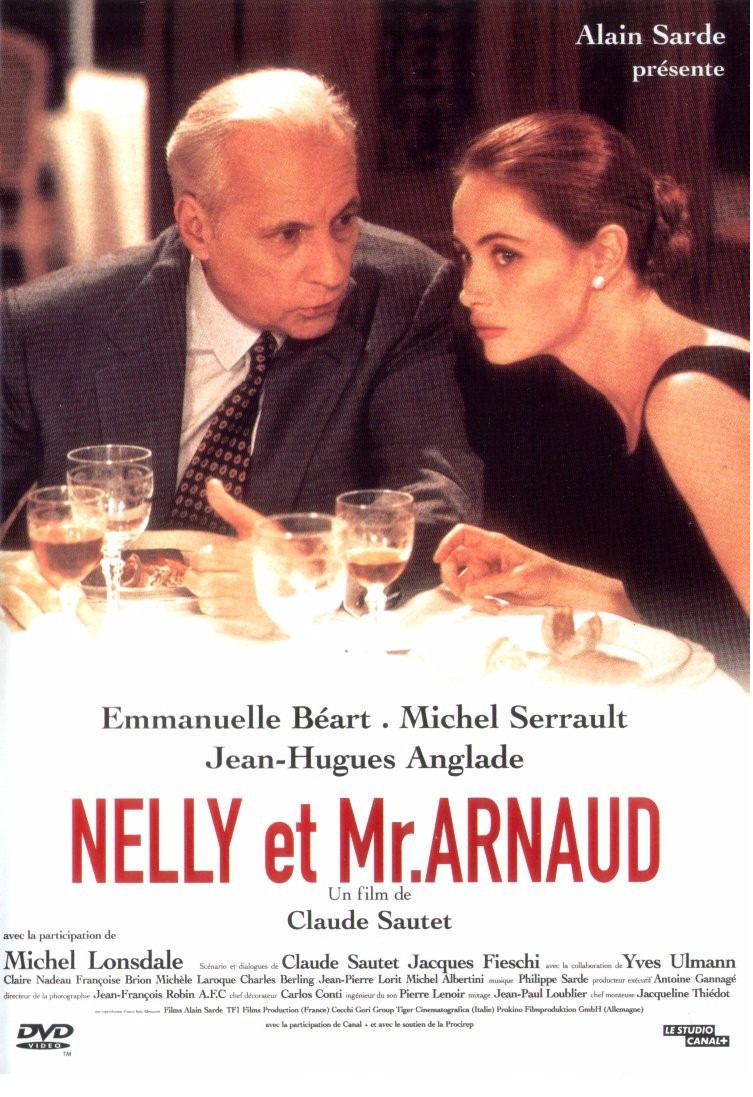

Nelly (Emmanuelle Beart) is young and beautiful, and poor, and married to an unemployed slug who is stuck in front of the television set all day.

Monsieur Arnaud (Michel Serrault) is old and rich, and married to a woman who has been living in Switzerland for years with another man. One day Nelly meets her older friend Jacqueline in a cafe, and they are joined by Arnaud, who was once Jacqueline’s lover.

Arnaud makes it clear he remembers meeting Nelly before: “Two years ago your hair was shorter, and lighter.” When Jacqueline leaves the table for a moment, he asks her personal questions, discovers she is in debt, and offers her money. She turns it down. “It was an honest offer,” he says. “I hope so,” she says. They part, but a connection has been made. Arnaud has declared his interest, and Nelly has started to think. She tells her husband that Arnaud offered the money, and she accepted it. She is testing him. He fails. She explains that she is leaving him. “You understand?” He nods. He does.

Arnaud gives Nelly the money, and she goes to work for him, editing his memoirs. He was once a judge, and then grew wealthy in real estate, “making Paris ugly.” They work day after day in his vast, book-filled apartment. She criticizes his manuscript. He quietly enjoys the attention. She makes changes.

“You butchered my text!” he cries. “You’re turning my book into a brochure!” They become like a married couple. No, not like a married couple, but like two halves of a strange whole: Despite their age difference, they fit. It’s not love. It’s an infinitely delicate emotional and intellectual dance.

Nelly is one of those women who is so beautiful that everything she does is about her beauty. Arnaud knows how beautiful she is. So do his friends. One night he takes her to a restaurant and buys a bottle of wine older than she is.

They talk about the possibility that Arnaud’s friends, across the room, assume she is a prostitute. They would be wrong. To begin with, there is no sex.

Although money is involved, Nelly is not with Arnaud because of money; it is simply that money makes it possible for her to be there.

But what do they want? Arnaud clearly wants to live with Nelly and be her lover, if he is not (as he fears) too old for that. On the other hand, equally clearly, he doesn’t want to make a fool of himself, either by being rejected or by being accepted and then finding he is unwilling to make the changes that a relationship would require. As for Nelly, she wants–well, you will have to decide for yourself. I think she finds Arnaud enormously attractive, not least because of his great reserve. She is attuned to the fact that she attracts him, and she enjoys attracting him. But does she want him to declare his attraction, or leave the two of them suspended in their state of exquisite erotic tension? And then there are others. Arnaud’s handsome young editor Vincent (Jean-Hugues Anglade), for example. He sees Nelly at Arnaud’s house and immediately asks her out. Arnaud is too proud to object to either one of them.

But he is possessive and jealous. In response to his questions, Nelly tells him she has slept with Vincent. She has not. She is setting him a test, just as when she told her husband about the money. Does Arnaud pass it? The question is too simple. It is more a case of whether he agrees to take the test.

“Nelly and Monsieur Arnaud” recently won two Cesar Awards, the French Oscars, for best director and actor. For Claude Sautet, the director, it is a return to the subject of romantic restraint; in his “Un Coeur en Hiver” (1993), also starring Beart, he dealt in a different way with a man who will not declare himself, who plays it safe and canny. These are films of great fascination. Beart is as talented and subtle as she is beautiful, and in this role, where so much goes unsaid, nothing goes uncommunicated.

Serrault, who is 68, made his first movie in 1955 (no less than “Diabolique”). He has done a lot of comedy (he was in all three “La Cage aux Folles” movies), but here he finds a gravity and intelligence that are indispensable to the character. And he avoids all temptations toward sentimentalizing the situation; he gives us no way to feel sorry for Arnaud, who demonstrates, especially at the end of the story, that he is quite able to take care of himself.

A movie like this is likely to appeal to the same kinds of people who admire the novels of Henry James. It is about the emotional negotiations of people who place great value on their status quo, yet find it leaves them lonely. Sometimes, of course, the alternatives to loneliness are not worth the price, and that is something to think about, especially for Monsieur Arnaud and perhaps even for Nelly.