Her brother has gone bonkers. He’s pouring all the booze down the drain and announcing he’s turning the pub into a worship center for Jesus people. Mona and Phil inherited the pub from their parents, and live upstairs; Phil (Paddy Considine) has come to Jesus belatedly, after a spell in prison. Mona (Natalie Press) gets on her moped, which has no engine but nevertheless functions as a symbol of escape, and wheels it into the country outside their small Yorkshire town. That’s the day she meets Tamsin.

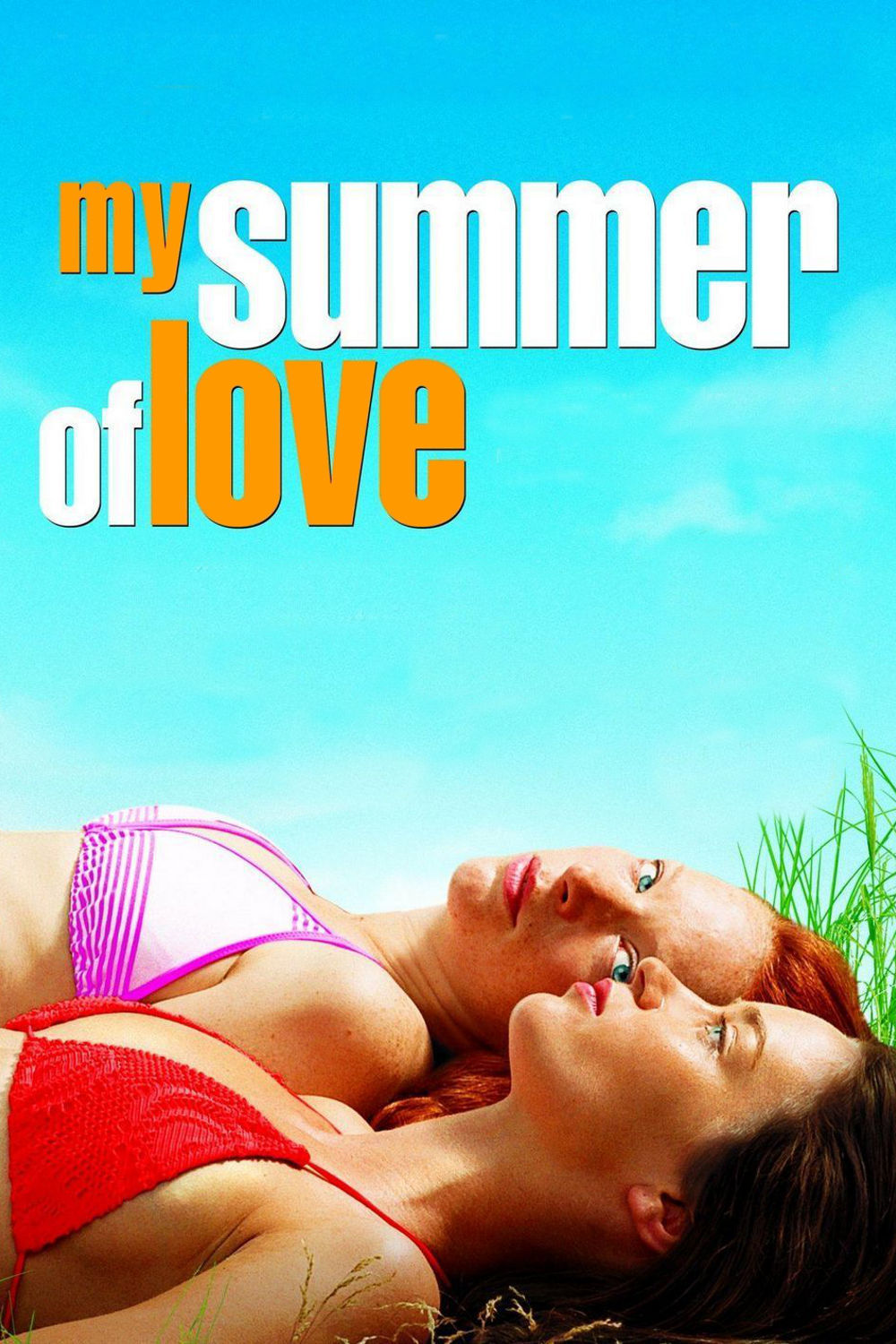

The title of “My Summer of Love” gives away two games at once: That she will fall in love, and that autumn will come. Mona is a tousled blond, 16 years old, dressed in whatever came to hand when she got up in the morning, bored by her town, her brother and her life. Her boyfriend has just broken up with her in a particularly brutal way. Tamsin (Emily Blunt) is a rich girl, about the same age, sleek and brunette, on horseback the first time Mona sees her. She’s spending the summer at her family’s country house. “You’re’ invited,” she tells Mona. “I’m always here.”

Tamsin’s mother is absent. Her father is present but seems absent. The first time Mona visits, Tamsin shows her the room of her dead sister: “It’s been kept as a shrine.” The sister died, Tamsin says, of anorexia. The country girl and the city girl become friends almost by default; there seems to be no one else in the town they would want to talk to — certainly not the members of Phil’s worship group.

That their summer leads to love is not quite the same thing as that it leads to a lesbian relationship. It’s more like a teenage crush, composed in equal parts of hormones and boredom. But Tamsin and Mona promise to love one another forever, and as they swim in forest pools and ride around the countryside they form their own secret society.

Phil in the meantime is engaged in the construction of a giant cross, made of iron and wood, which he wants to place on the top of a hill overlooking the town. Mona passes through the pub on her way upstairs, avoiding the prayer groups; left unexplained is how the brother and sister are supporting themselves. For Phil, religion seems less a matter of spiritual conviction than emotional hunger; he has been bad, now is good, and requires forgiveness and affirmation. Nothing wrong with that, unless he begins to impose his new lifestyle on Mona.

The movie is sweet and languid when the girls are together, edgier when Mona is around Phil. The question of Tamsin’s father is complicated by the presence of his “personal assistant.” The big summer house is empty and lonely, lacking a mother and haunted by the ghost of the dead sister. Pawel Pawlikowski, the director and co-writer (with Michael Wynne), wisely allows then time to seem to flow, instead of pushing it. That’s why, when Phil visits Tamsin’s house looking for Mona, how Tamsin behaves and what happens is such a cruel surprise. She is, we realize, a convincing actress. When more revelations come in a closing scene, they are not exactly a surprise, not exactly a tragedy, not exactly very nice. We begin to sense the buried irony in the title.

Emily Blunt is well-cast as Tamsin, a rich girl, product of the best schools, who cultivates decadence as her way of standing apart from what’s expected of her. Natalie Press as Mona, on the other hand, is straight from the shoulder: She’s without illusions about life, has given up on her brother, looks forward to marriage and family as a dreary prospect. Without quite saying so, she knows she’ll never find a husband in her Yorkshire valley who is up to her speed. Will she, after this summer, identify as a lesbian? Doubtful. The summer stands by itself.

I’m not sure if the movie has a point. I’m not sure it needs one. I learn from Variety that the screenplay is inspired by a novel by Helen Cross that also involves a miner’s strike and some murders. All of that is missing here, and what’s left is a lazy summer of sweaty uncertain romance; this isn’t a coming-of-age movie so much as a movie about being of an age. At the end, when Tamsin tries to explain herself to Mona, we understand how completely different these two teenage girls are; how one deals in irony and deception, and with the other what you see is what you get, whether you want it or not.