“You can’t teach American history without talking about Pauli Murray,” we’re told early on in “My Name is Pauli Murray.” You may agree by the end of this informative documentary. Directors Julie Cohen and Betsy West let their subject narrate an incredible life that influenced students, civil rights leaders and more than one future Supreme Court justice. Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Thurgood Marshall used Murray’s ideas and research in their most famous court cases. The filmmakers draw attention to how prescient and forward thinking those ideas were, pointing out how the ACLU used them as late as 2020 to ensure that LGBTQ+ rights were upheld. If this were a dramatic feature, I’m not sure my suspension of disbelief would be elastic enough to withstand the achievements presented here. Truth is indeed stranger, and more amazing, than fiction.

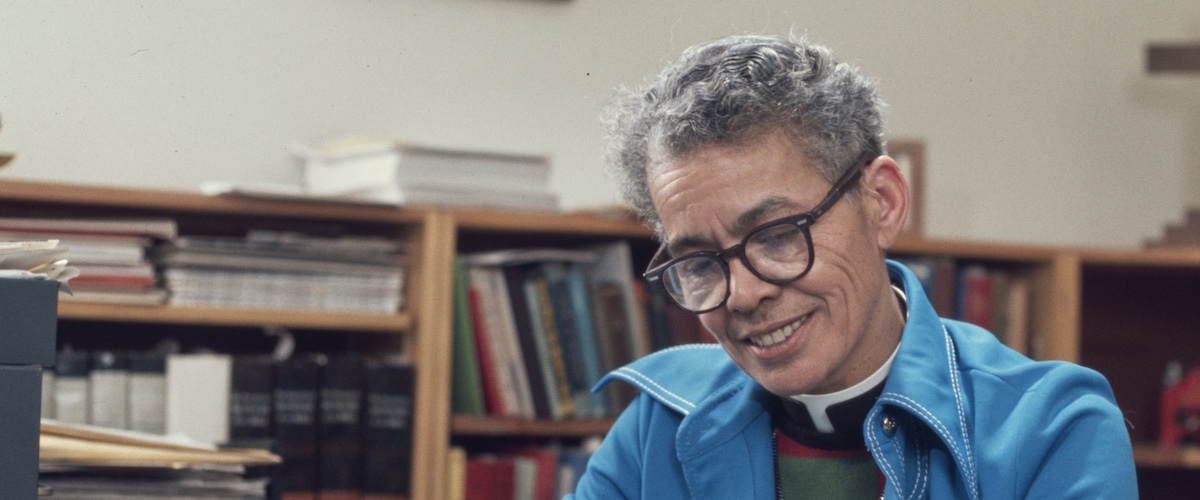

In a life spanning 74 years, Pauli Murray was a lawyer, a poet, an activist, a teacher, and an Episcopalian priest, the first Black woman to be ordained. Murray was also what we refer to as non-binary, proving that, as one person says in the documentary, this existed long before people spoke openly about it. However, we discover that Murray did try to express it, and at one point sought out exploratory surgery to see if undescended male genitalia were present. At times, and for safety during the Depression-era days of riding the rails, Murray’s appearance and dress was that of a teenage boy. Letters reveal someone who felt they were in the wrong body.

One thing that wasn’t discussed in those correspondences was preferred pronouns, presumably because the idea did not exist at the time. In biographies, Murray is referred to as “she” and “her,” and her own memoir, which we hear recordings of, is written in the first person. West and Cohen give time to a non-binary activist who acknowledges the use of feminine pronouns but decides to use “they” when they refer to Murray. When in doubt, I would normally ask a person’s preference, but such a case is not possible here. I will use “she” and “her” here, with no malice or disrespect intended.

In fact, there’s a section of “My Name is Pauli Murray” that’s all about identification and how the perceived wrong terminology can foster dissent. Murray taught students during the 1960s, bringing decades of firsthand civil rights struggle expertise to the classroom. Yet the students rejected her preference for using “Negro” instead of “Black,” going so far as to label their professor an Uncle Tom. We hear the reasoning behind the choice—“black” was never capitalized and was therefore considered demoralizing—but this was the “Black is Beautiful” era and, as one friend points out, these students were as fiery and outspoken as Murray was 30 years prior when Eleanor Roosevelt was getting pelted with typewritten letters chewing out FDR for his half-hearted anti-lynching statements.

Because of those letters, Mrs. Roosevelt and Murray formed a friendship spanning several decades. The First Lady became something of a motherly figure and cohort who also shared several life experiences: for example, the two were both orphaned and raised by older relatives. The Murray clan were a multi-ethnic group, some of whom could pass for White, and they all instilled the idea that a woman could do anything. Impressed by her friend’s strong will and fearlessness in confronting anyone regardless of their stature, Mrs. Roosevelt quite often suggested Murray as a valuable resource to people like JFK. “My Name is Pauli Murray” also blesses us with my all-time favorite Ebony magazine cover, the hilarious one where Roosevelt proclaims “Some of My Best Friends Are Negroes!”

To the world, Pauli Murray was a woman, and was treated as such. Sexism came from Blacks as well as Whites. “People talk about Jim Crow,” she wrote, “well, I’m dealing with Jane Crow.” This intersection of race and gender would become a constant talking point for Murray—again, far ahead of the times—and this included some clever uses of the 14th Amendment to force some semblance of equality in the law. After being denied acceptance in a PhD program, she enrolled in Howard University’s law school. “I don’t know why women would even consider the law,” a professor said. And during the first year, Murray “wasn’t even allowed to speak.” After graduating at the top of the class, Murray’s automatic acceptance into Harvard to continue studies was rescinded because it was for men only.

“My Name is Pauli Murray” isn’t just a list of achievements, each more impressive than the last. It’s also a bit of a love story between Murray and Irene “Renee” Barlow. The two met at the law firm they both worked at, gravitating toward one another because they were two of the few women in a jungle full of men. We hear snippets of a few letters between the two, and Murray mentions her as “my closest friend” on the tapes that were recorded during the writing of a second memoir, Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage. When Yale recently created Pauli Murray College, it made the pioneer the first Black and LGBTQ+ person to have an institute named after them.

Before this film, I didn’t know very much about Pauli Murray. It does what all good documentaries do: it made me want to read up and be educated more on its subject. And what a great and inspiring subject Pauli Murray is.

Now playing in select theaters, and available on Amazon Prime on October 1.