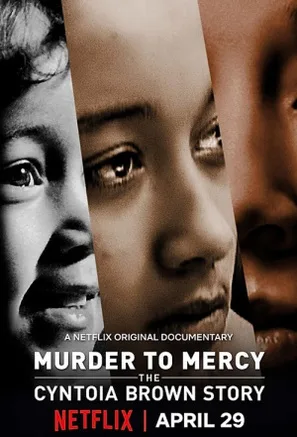

Daniel H. Birman’s “Murder to Mercy: The Cyntoia Brown Story” is what happens when a crime documentary loses sight of its focus. By the credits, the film leaves out the critical voice of its subject, Cyntoia Brown Long, a once-troubled teen who grew up to be a prison reform advocate. The film sticks so closely to the chronological timeline of the case that it sacrifices any kind of artful storytelling. About half of this documentary’s footage looks like it came from Birman’s original film on Brown, “Me Facing Life: Cyntoia’s Story.” The newer footage suffers from a stilted sense of detachment from Brown. However, Birman’s contribution to the outcome of this story is fairly centered, making “Murder to Mercy” feel more like a victory lap for the filmmaker than for his subject.

The documentary begins with Brown in the early days of her case. Brown had been forced into prostitution by her boyfriend at the time and her latest pickup made her feel like her life was in danger. She shot him before he could hurt her, landing the teenaged Brown in jail and launching her into a downward spiral into the depths of the American criminal justice system. She naively trusted the police, waving away her Miranda Rights that would have given her the right to an attorney during questioning. Eventually, she would be shuffled to the adult criminal population and face even harsher sentencing. This is the journey Birman documented in his documentary for PBS on Brown, “Me Facing Life.” In one of the film’s interviews, Brown’s biological mother admitted to drinking heavily while pregnant, a revelation that would fuel one of the first efforts to petition for a commuted sentence. Birman includes the praise of his work in his new film “Murder to Mercy,” as if to make sure audiences today would know that he had a hand in making Brown’s story known across the country.

But worse than the showy gesture of patting himself on the back, Birman loses the core voice of his story. Either because Brown was no longer as available as she was at the beginning of his project some 14 years ago or she didn’t wish to participate as time wore on, Brown takes a significant step back from the spotlight in the second half of the film. To fill in the gap and explain other details of the case, Birman assembles together Brown’s new pro-bono lawyers, energized by Birman’s previous documentary, for a series of interviews. The documentary, which once spent so much more time with Brown in her earlier days, then becomes the stuff of speculation and armchair psychology as diagnosed by mostly white older men. New interviews with Brown’s biological and adopted moms tap into issues of poverty and Black pain without looking at the system that failed Brown multiple times in her young life.

The parade of sad stories unravels in journalistic fashion, one date follows the next in a graceless, graphic-filled intertitle. Watching this image repeat over and over again feels like reading a book where a new chapter starts every three paragraphs. It constantly interrupts the flow of the story for very little reason. With Brown’s near-absence in the second half of the documentary, watching others speak for her was a grim reminder that she is still fighting to be seen on her own terms, and not a problem child to be talked over by grown-ups. There are likely many other people in her position who survived unspeakable abuse as children only to be failed by systems meant to protect them over and over again. Brown’s story has already inspired change, especially when it comes to redefining legal terms to recognize exploited children, but I want to hear more about her—preferably from her—in future documentaries about her story.