In many lives there is a crossroads. We make our choice, and follow it down to the present moment. Still inside of us is that other person, who stands forever poised at the head of the path not chosen. “Mrs. Dalloway” is about a day’s communion between the woman who exists, and the other woman who might have existed instead.

The film’s heroine muses that she is thought of as “Mrs. Dalloway” by almost everybody: “You’re not even Clarissa any more.” Once she was young and fair, and tempted by two daring choices. Peter would have been a risk, but he was dangerous, and alive. Even more dangerous was Sally, with whom flirtation threatened to develop into something she was unwilling to name. Clarissa took neither choice, deciding instead to marry the safe and sound Richard Dalloway, of whom young Peter sniffed, “He’s a fool, an unimaginative, dull fool.” Now many years have passed. Mrs. Dalloway is giving a party. The caterer has been busy since dawn, the day is beautiful, and she walks through Hyde Park to buy the flowers herself. So opened Virginia Woolf’s famous 1923 novel, which followed Clarissa Dalloway for a day, using the new stream-of-consciousness technique that James Joyce was experimenting with. We will follow her through until the end of her party, during a day in which no one she meets will know what she’s really thinking: All they will see is her reserved, charming exterior.

The novel stays mostly within the mind of Clarissa, with darts into other minds. Film cannot do that, but “Mrs. Dalloway” uses a voice-over narration to let us hear Clarissa’s thoughts, which she never, ever shares with anybody else. To the world she is a respectable 60-ish London woman, the wife of a cabinet official. To us, she is a woman who will always wonder what might have been.

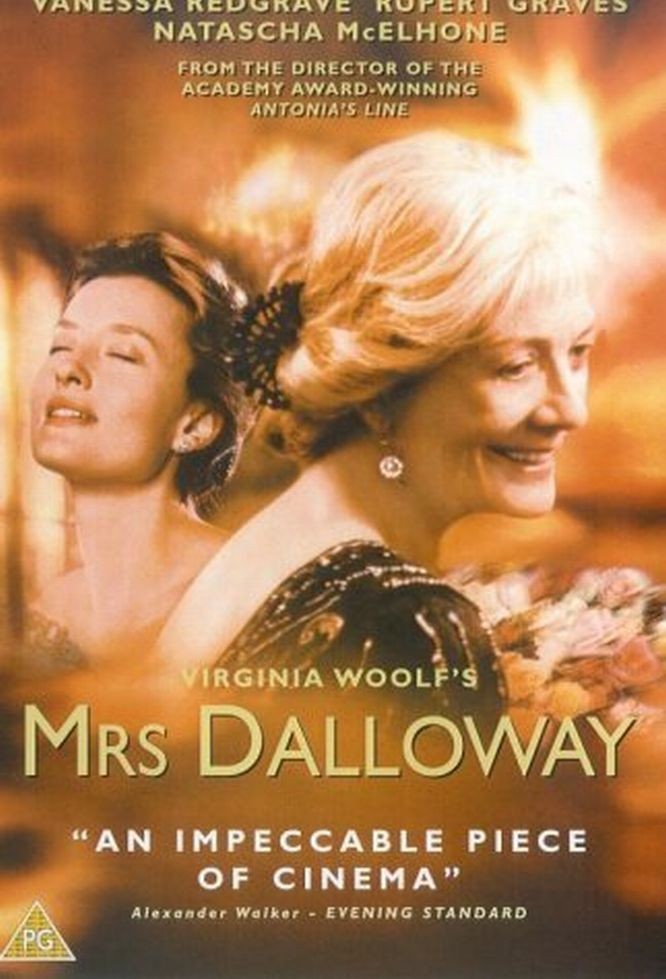

Vanessa Redgrave so loved the novel that she commissioned this screenplay by Eileen Atkins, an actress who has been involved in a lot of Woolf-oriented stage work. Redgrave of course seems the opposite of a woman like Clarissa Dalloway, and we assume she has few regrets. But we all wonder about choices not made, because in our memories they still glow with their original promise, while reality is tied to the mundane.

As the film makes its way through Clarissa’s day, there are flashbacks to long-ago summers when young Peter (Alex Cox) was courting young Clarissa (Natascha McElhone), and young Sally (Lena Headey) was perhaps courting her, too, although the movie is cagier about that than the novel. But Woolf is too wise to let Peter and Sally remain in the sunny past of memory. They both turn up on this day.

In middle age, Peter (Michael Kitchen) is rather pathetic, just returned from what seems to have been an unsuccessful romance and career in India. And Sally (Sarah Badel) is now the distinguished Lady Rossiter. There is a wonderful scene where Peter and Sally find a quiet corner of the party, and he tells her of Clarissa, “I loved her once, and it stayed with me all my life, and colored every day.” Sally nods, keeping her own thoughts to herself. We gather that Sally, in middle age, may be practicing the same sort of two-track thinking that Clarissa uses: Both women see more sharply, and critically, than anyone imagines, although with Sally, we must guess this from the outside.

There is another crucial character in the film. Unless you’ve read the novel you may have trouble understanding his function. This is Septimus Warren Smith (Rupert Graves), who in an early scene watches as a friend is blown up in the No-Man’s Land of the trenches in France. Now five years or more have passed, but he suffers from shell-shock and has a panic attack outside a shop where Clarissa pauses. She sees him, and although they never meet, there is a link between them: Both have seen beneath the surface of life’s reassurance, to the possibility that nothing, or worse than nothing, lurks below. Woolf is suggesting that World War I unleashed horrors that poisoned every level of society.

The subtext of the story is suicide. Woolf is asking what purpose is served by the decisions of Clarissa and Septimus to go on living lives that they have seen through. A subtle motif throughout the film is the omnipresence of sharp fence railings–spikes, like life, upon which one could be impaled.

The director, Marleen Gorris, previously made the Oscar-winning Dutch film “Antonia's Line,” about a woman who makes free choices, survives, and prevails. Here is the other side. It’s surprising that Gorris, who was so open about Antonia’s sexuality, is so subtle about the unspoken lesbianism in Woolf’s story, but it’s there for those who can see it.

More important is the way she struggles with form, to try to get an almost unfilmable novel on the screen. She isn’t always successful; the first act will be perplexing for those unfamiliar with the novel, but Redgrave’s performance steers us through, and by the end we understand with complete, final clarity what the story was about. Stream-of-consciousness stays entirely within the mind. Movies photograph only the outsides of things. The narration is a useful device, but so are Redgrave’s eyes, as she looks at the guests at her party. Once we have the clue, she doesn’t really look at all like a safe, respectable, middle-aged hostess. More like a caged animal–trained, but not tamed.