“Honest to God,” the man tells the woman, “I never thought to see you in such a state. You must miss him dreadfully.” Between ordinary people, ordinary words. Between a commoner and a queen, sheer effrontery. How can this bearded man, a Scotsman who oversees Queen Victoria’s palace at Balmoral, have the gall to look her in the eye and address her with such familiarity? The atmosphere in court is instantly tense and chilling. But the man, John Brown, has caught the queen’s attention and cut through the miasma of two years’ mourning for her beloved consort, Prince Albert. The little woman–a plump pudding dressed all in black–looks up sharply, and a certain light glints in her eyes. Before long she is taking Brown’s advice that she must ride out daily, for the exercise and the fresh air.

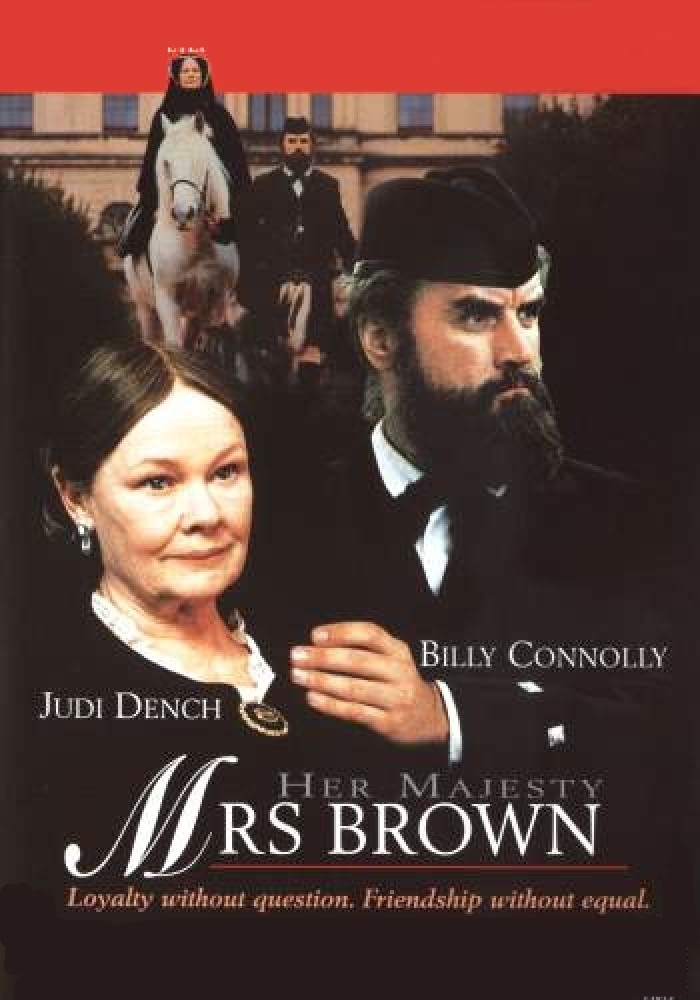

“Mrs. Brown” is a love story about two strong-willed people who find exhilaration in testing each other. It is not about sexual love, or even romantic love, really, but about that kind of love based on challenge and fascination. The film opens in 1864, when Queen Victoria (Judi Dench), consumed by mourning, has already been all but invisible to her subjects for two years. Her court coddles and curtseys to her, and that’s what she expects: A nod or a glance from her can subdue an adviser.

Her household thinks perhaps riding might help her break out of her deep gloom. Import John Brown (Billy Connolly), a Scotsman in a kilt, arrives with one of the queen’s horses and is promptly ignored. Not to be trifled with, he stands at attention in her courtyard, next to the horse. The next day he is there again. Proper behavior would have him waiting, docile and invisible, in the stables. “The queen will ride out if and when she chooses,” Victoria informs him.

“And I intend to be there when she is ready,” Brown informs Victoria.

Nobody in her life had spoken to her in this way, except perhaps for the beloved Prince Albert. A charge forms in the air between the queen and her servant. Victoria is a complex and observant woman, who knows exactly what he is doing and is thrilled by it: Queens perhaps grow tired of being fawned upon. Soon Brown and the queen are out riding, and soon the color has returned to her cheeks, and soon Brown is offering advice on how she should manage her affairs, and soon the household and the nation are whispering that this beastly man Brown is the power behind the throne.

“Mrs. Brown,” they called her behind her back. Her son the Prince of Wales (David Westhead) is enraged to find that at Brown’s order, the smoking room is to be closed at midnight (“Mr. Brown needs his rest,” the queen serenely explains). Brown takes her riding in the country and they call at a humble cottage, and the queen is offered Scotch whisky. The national newspapers raise their eyebrows. Finally the prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli (Antony Sher), pays a visit to see for himself what is happening in the royal household.

Judi Dench has long been one of the reigning stars of the London stage. She often plays strong-willed, intelligent women. She has never been much interested in the movies, although she did play “M” in a Bond film. This is her first starring role. She is wonderful in it, building the entire character on the rock of utter self-possession, and then showing that character possessed by another. Entrenched behind her desk, dressed in mourning, coils of braids framing her implacable face, she presents such a formidable facade that it is curiously erotic when Brown melts through it.

Billy Connolly is also little-known in films; he is a stand-up comic, I learn, although here he has the reserve and self-confidence that most stand-up comics lack almost by definition. There is a manliness to him, a robust defiance of the rules. He also drinks too much, and although he seems for a long time able to hold it, one of the movie’s subtle themes is that the better he gets to know the queen the less sure he is of how he should proceed.

Would there be, could there be, physical sex between them? Almost certainly not. But they both tacitly recognize that they might enjoy it. The queen is not an attractive woman, but she is powerful, and power is thrilling; in one key scene Brown swims naked in the highlands, intoxicated by his closeness to the throne. Victoria is like a movie nun–like Deborah Kerr in “Black Narcissus”–in being all the more intriguing because she’s forbidden.

“Mrs. Brown” was written by Jeremy Brock and directed by John Madden, whose first film, the torturous “Ethan Frome,” gave little promise of his confidence here. The movie is insidious in its methods, asking us to see what is happening beneath the guarded surfaces. The behavior of a queen and her servant is so minutely dictated by rules and customs that they may look much the same when breaking them as when following them. So much depends on the eyes.