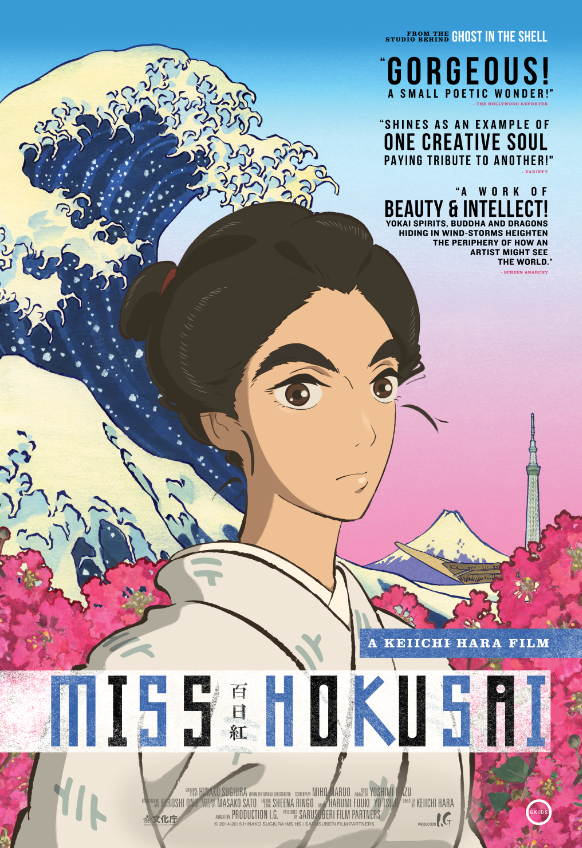

Keiichi Hara’s “Miss Hokusai,” an adaptation of the Hinako Sugiura manga series, is an undeniably unique biopic, and not merely because it’s an animated one. Rather than tell a traditional tale of a famous artist—in this case, Katsushika Hokusai, a legendary Japanese painter most well-known for the world-famous “The Great Wave”—it allows us to see him through his daughter’s eyes, and to do so with a most unusual style. In fact, Hara opens with a series of scenes designed to let you know that this is not a traditional narrative, something he clearly feels reflects his subject’s diverse artistic output. Narrated by O-Ei Hokusai, the painter’s daughter, we see Hokusai painting a giant rendering of an old man, followed by him painting two sparrows on a grain of rice. His art knows no physical boundaries. Then, as O-Ei crosses a gigantic bridge in Edo in the Summer of 1814, we hear hard rock guitar riffs on the soundtrack. An appropriate response is confusion.

Sadly, this striking opening isn’t really fulfilled upon. Over the next 90 minutes, “Miss Hokusai” weaves a defiantly episodic patchwork quilt of moments in Hokusai’s life. Likely an impact of the source material, “Miss Hokusai” is structured in a way that’s designed to work better as a series of short stories than a feature film. The pace of the film gets clunky rather quickly when it needs to be lyrical in order to work. And “Miss Hokusai” is remarkably talky. It’s filled with conversations about other artists of the period and discussions of the philosophy of art. As much as I wanted to be transported to the world of “Miss Hokusai,” it felt more like an analytical examination of a period and one of its most artistic voices, and I could never quite engage with that aspect of it.

Between the lengthy dialogue scenes, there are moments of visual beauty. I like the way Hara uses natural light—from the dim glow of a lantern to the vibrant orange of a sunset. And some of the “wide shots” are breathtaking, capturing Edo, which would become Tokyo, as a bustling, moving, happening city, even two centuries ago. And there are “episodes” within “Miss Hokusai” that are effective as short films on their own. In the film’s best segment, Hokusai discusses feeling one night like his hands were leaving his body, traveling the world without him but still attached back to their owner, almost like an out-of-body experience. The parallel between this approach to art—tactile and experiential—and his daughter’s, which is more intellectual and technique-based, is interesting, but, like so much of “Miss Hokusai,” underdeveloped.

“Miss Hokusai” might have been more effective if it had stuck to one tone within its episodic structure, or more fluidly moved from one to another. But a segment like the one above, clearly designed to raise a talking point about artistic approach, might be followed by one of many with O-Ei’s blind, sick younger sister O-Nao, during which the film descends into sentimentality. The idea that O-Nao’s father, while painting art that would resonate centuries later, basically ignored his sick child, is a fascinating one but it’s better served by a documentary than episodically within an animated film.

While there’s something undeniably ambitious about approaching the life of an artist in a way that’s designed to reflect his breadth of skills, and to even question the origins and purpose of art while doing so, there’s still a basic filmmaking pacing that’s lacking in “Miss Hokusai.” It feels much longer than its 90 minutes, and I left it feeling like I didn’t really learn much about its title character or her father.